Philosopher, linguist, and social critic Noam Chomsky recently spoke about his experiences in campus activism and his vision of a just society to help inaugurate the Next System Project’s ambitious new teach-ins initiative taking place across the country. An initial signatory to the Next System statement, Chomsky explores the connections between culture, mass movements, and economic experiments—which in “mutually reinforcing” interaction, may build toward a next system more quickly than you may think.

Next System Project: As the Next System Project engages in dozens of university campus-based teach-ins across the country, what do you think of such approaches to engaging campus communities in deep, critical inquiry—can they help transform our society?

Noam Chomsky: Maybe I can just give a taste of my own personal experience. I’ve been at MIT, where I still am, for 65 years. When I got here it was a very quiet, passive campus: all white males, well-dressed and deferential, doing their homework, and so on. It remained that way right through most of the 1960s, through all the campus turmoil. There were some people involved, but not much. There was faculty peace and justice activity but not much on the part of students.

In fact, the campus was so passive that in 1968 when the Lyndon Johnson administration was beginning to try to slowly pull out of the Vietnam War, they had an idea that they would make peace with the students. They decided to send around the worst possible choice—the former Harvard dean, McGeorge Bundy—who they thought would know how to talk to students. He would come to campuses and we’d all make friends. They started off by picking very safe campuses. MIT was the second on the list, but they made a mistake. It turned out that there’d been a couple of students who had been actively organizing on campus. When Bundy showed up, he was surrounded by angry masses of students demanding that he explain and justify the terrible things he’d been involved in, and that essentially ended that effort.

By that time, really a handful of students had succeeded in substantially organizing the campus on a whole variety of issues that were very much alive. The Vietnam War, racism, the beginnings of the women’s movement were just starting and taking off then. In fact, within a couple of years, MIT became probably the most active and radical campus in the country. Mike Albert, who was one of the leaders of this group, was elected student body president with a set of positions so radical you could hardly believe them. Without going into the details, it had a major change, a major impact on the culture, the community.

For the first time, there began to be serious discussion of the questions of the ethical elements in technological development. That all goes right to the present. In fact, just a few minutes ago, I was on a Reddit-style interchange with students on a whole variety of questions. They were bringing up all kinds of issues. This would’ve been utterly unthinkable back in the early 1960s. And similar things have been happening on all campuses. That’s had a big effect. It’s changed the culture, it’s changed the society. If you look over the developments in recent years, there’s been severe retrogression on economic and political issues, but considerable progress on cultural and social issues. The class nature of the society and its basic institutions have not only not changed, they’ve gotten worse. In other respects, there’s been major changes and it matters: attitudes towards women’s rights and civil rights, opposition to aggression, concern over the environment, these are all major things that have changed. Student activism has been critical all the way through and continues to be.

There’s a reason for that. Not just here, historically. Students typically are at a period of their lives when they’re more free than at any other time. They’re out of parental control. They’re not yet burdened by the needs of trying to put food on the table in a pretty repressive environment, often, and they’re free to explore, to create, to invent, to act, and to organize. Over and over through the years, student activism has been extremely significant in initiating and galvanizing major changes. I don’t see any reason for that to change.

Next System Project: Why do you think that right now, a deeper conversation on the retrogression in the political and the economic structures of our society is something that’s worth doing, and where do you think that might lead?

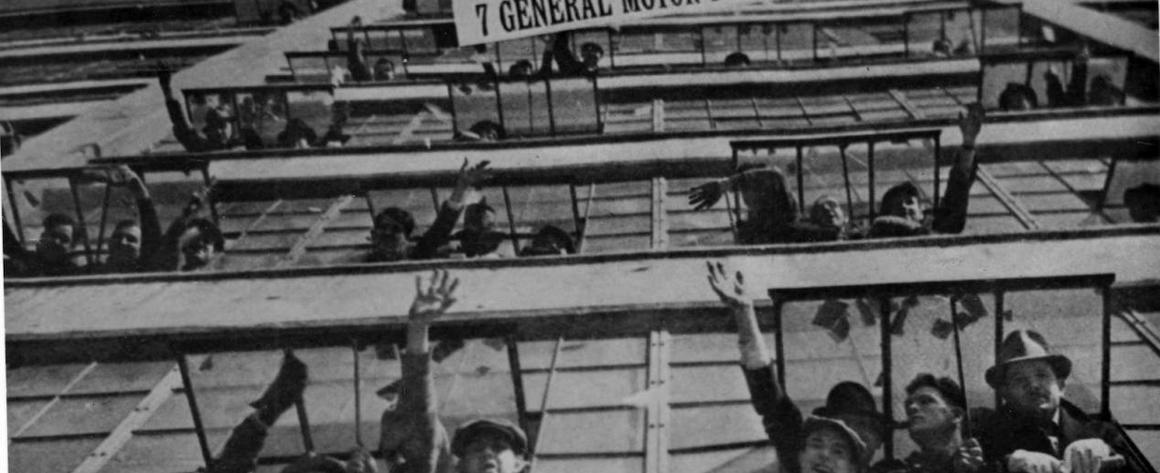

Noam Chomsky: Let’s take a look at a longer stretch. The Great Depression in the 1930s, if you compare it with today, was quite different in important ways. I’m old enough to remember. It was objectively much worse than today, much more severe. Subjectively, it was much better. It was a period of hopefulness of my own extended family, mostly unemployed working class, very little education—not even high school, often. They were active, organized, hopeful. There was militant labor action—the CIO at the early years was smashed by force, but by the mid-1930s it was becoming very significant. The CIO was organized. The sit-down strikes were really threatening capitalist control of the productive institutions, and they understood it. There was a relatively sympathetic administration, and though there were political parties that were functioning in a variety of ways, the unions offered not only activism, but solidarity, mutual support, cultural interchange. It was a way of life that gave people hope that we’re gonna get out of this soon though, no matter how bad it is.

There were significant gains. The New Deal gains were not trivial—there were a lot of problems with them, but major gains. By the late 1930s, there was already a backlash beginning from the business classes that were used to running the show. It was kind of held off during the war, but launched strongly with real dedication after the war. There were major campaigns to roll back the kind of radical democracy that had developed during the Great Depression and the war not just in the United States, but throughout the world. That continues right up to the present.

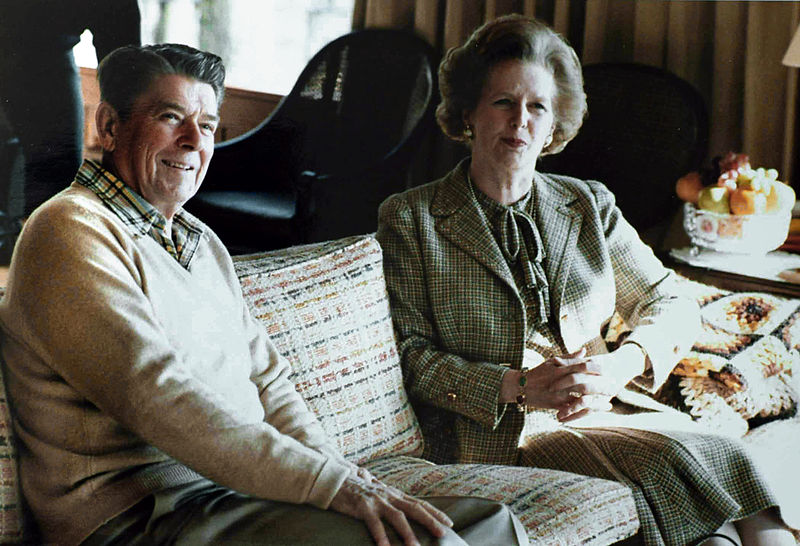

There was plenty of activism in the ‘60s, which led to concern and backlash, which took off in the ‘70s and especially under Reagan and since with the neoliberal programs, which have been pretty much a disaster wherever they’ve been applied, all over the world, in different forms. In the United States typically what they’ve done is undermine the welfare and opportunities for the majority of the population and also undermined functioning democracy. That’s consistent everywhere. If you look at, let’s say, real male wages, they’re about what they were in the 1960s. There’s been growth—not as strong as in earlier years, but substantial—but going into very few pockets.

For example, since the last great crash, 2008, probably 90% of growth has gone to maybe 1% of the population. The political system was never really responsive to the mass of the population, but it’s now changed to the point where it’s a virtual plutocracy. If you look at academic, political science, it shows that maybe 70% of the population is just underrepresented. Their representatives pay no attention to their attitudes.

Years ago, it was pointed out that if you look at the socioeconomic profile of abstention in the United States—non-voting—it’s pretty much the same bloc of people as those in comparable societies, like, say, in Europe, where these blocs vote for labor-oriented or social democratic parties, which don’t exist here. We have geographic parties, which actually come straight out of the Civil War—just business-run parties, no class-based parties. And all of this has gotten much worse. It’s led to a very dangerous potential of people who are angry, isolated. It’s very different from the ‘30s in that the hopefulness is gone. The hopefulness and the solidarity has been replaced by isolation, anger, fear, hatred, easy target for demagogues as we see right in front of us constantly. It’s a dangerous situation that can be countered and students are in a really good position to counter it—and to address the fundamental institutions, economic and political institutions of this society, which are closely related.

There are major threats that are related to this that just can’t be discounted. The human species is now at a point where it has to make choices that are going to determine whether decent survival is even possible. Environmental catastrophe, including war, maybe pandemics, these are very serious issues and they can’t be addressed within the current structure of institutions. That’s almost given. There have to be real significant changes, and only really effective popular mass-based movements can introduce and carry forward such initiatives, as indeed did happen during the 1930s.

Next System Project: A recent poll of 18-to-26-year-olds found that they believe by 58% that socialism “is the most compassionate political system” with an extra 6% saying “communism.” There seems to be a groundswell within this younger generation for an interest in socialism, but it seems at this point very inchoate. Is this a moment to delve into questions of ownership, control, and the design principles that would produce institutions that generate community, sustainability, and peace? Or is it too academic a pursuit given how distant a powerful, mass-based political project is at the moment?

Noam Chomsky: I’m not sure how far away we are, frankly. Just take the last crash. One of the consequences was the government basically took over the auto industry. They had some choices. One choice was the one that was taken: tax payroll, bailout the owners and managers, and then restore the system to what it was. Maybe new names, but essentially the same structure, and have them continue to do the same thing: produce automobiles. That was one choice. That was what was taken. There was another choice. The other choice was to hand the system over to the workforce, have it democratically controlled and managed, and have the production oriented toward what the community needs. We don’t need more cars. We need effective mass transportation for lots of reasons. You can take high speed trains from Beijing to Kazakhstan, but not from Boston to New York. Infrastructure’s collapsing, it has a horrible effect on the environment. It means that spending half your life in traffic jams. This is implicit in market systems. A market gives you choice among consumer goods, say a Ford and a Toyota. It doesn’t give you a choice between an automobile and a decent mass transportation system.

Those are choices that involve communities, solidarity, popular democracy, popular organizations and so on. That was a choice just a couple of years ago with a different constellation of popular forces. I think the choice could have been an alternative one. That’s happened right near where I live in a suburb of Boston. There was a pretty successful manufacturing plant producing parts for aircraft and so on. The multinational that owned it decided they weren’t making enough profit, so they decided to put them out of business. The progressive union offered to buy it from them, which would have been profitable for the multinational, but I think mainly for class interests they refused. If there had been popular support for that right here, I think the workers could have taken it over and they would have a successful worker-owned and -managed enterprise. Those things can proliferate.

My feeling is it’s not really remote. I think most of these things are right below the surface in people’s consciousness. It has to be brought forward. This is true of many issues incidentally. It’s very important to recognize how unresponsive the political economic system is to people’s attitudes. You see this all the time. Take, say, Bernie Sanders. His positions are regarded as radical and extremist. In fact if you look at them, they’re very much in accord with the popular will over long periods. Take, say, national healthcare. Right now about 60% of the population are in favor of it, which is pretty remarkable since nobody speaks for it and it’s constantly demonized. If you look back, that’s consistent. In the late Reagan years about 70% of the population thought it should be in the Constitution, such a natural right, and in fact about 40% of the population thought it already was in the Constitution.

That’s consistent right through. It’s called politically impossible, meaning the financial institutions and the pharmaceutical corporations won’t accept it. But that tells you something about the society, not the popular will. Same is true for other things: free tuition, higher taxes on the rich, all consistent over long periods, but the policy goes in the opposite direction. If popular opinion can be organized, mobilized, with institutions of interaction and solidarity, like unions, then I think what’s right below the surface can become quite active and implemented as policy.

Next System Project: What’s your approach in terms of the principles or the models by which we can really engage the questions of ownership and democracy in the economy? Is it a worker-centered vision? A community vision? Would the economy function on principles of subsidiarity? And what do you do about large industry? Do you mix and match some of the principles, competing interests, and goals that are inherent to different institutions to create a national-level strategy?

Noam Chomsky: My feeling is that all of those initiatives should be pursued, not just in parallel, but in interaction, because they’re mutually reinforcing. If you have, say, worker-owned and -managed production facilities in communities which have popular budgeting and true democratic functioning, those support each other, and they can spread. In fact they might spread very fast. The example that I just mentioned of the Boston suburb for example, can be duplicated all over the place. People like David Ellerman were working on efforts like this for years. Over and over, you get situations where some multinational will decide to put out of business a profit-making subsidiary, which isn’t profitable enough for their bottom line, but works fine for the workers. Frequently, the workforce has tried to take it from them and take it over. Often they refuse even though they would make more profit than just giving it up—I think for good reason: they comprehend that this can proliferate. If some things work, others will follow.

There are some, in fact, pretty substantial ones in the world like Mondragon—not perfect by any means, but a model that can be developed and extended here. I think it does appeal to people. We might just consider the matter of wage labor. It’s pretty hard to remember maybe, but if you go back to the early industrial revolutions, the late 19th century, wage labor was considered essentially the same as slavery. The only difference was that it was supposed to be temporary. That was a slogan of the Republican party: opposition to wage slavery. Why should some people give orders and others take them? That’s essentially the relation of a master and a slave, even if it could be temporary.

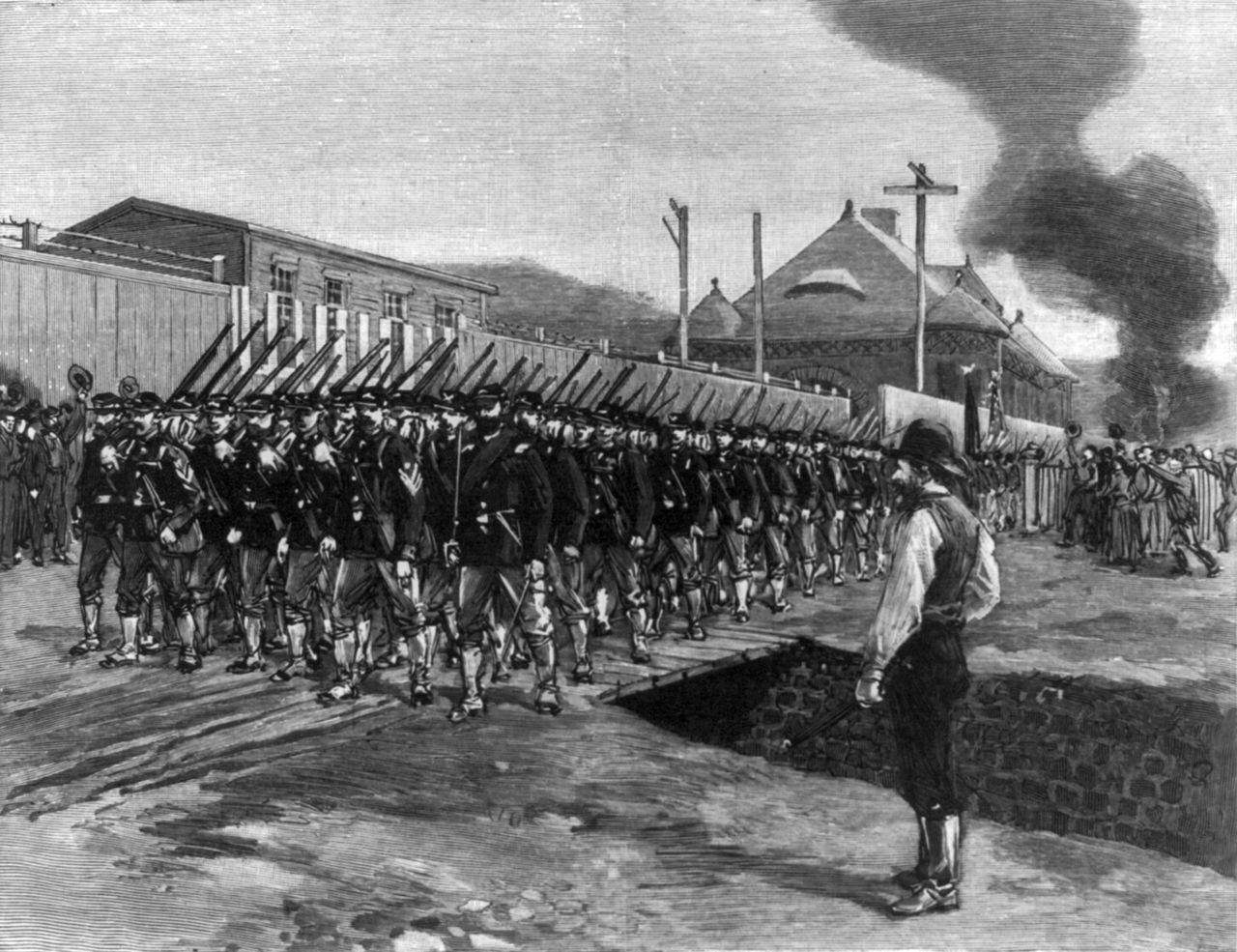

If you look back at the labor movement in the late 19th century, you see it had a rich array of worker-owned, worker-directed media: worker-written newspapers all over the place, and many of them by women—the so-called “factory girls” in textile plants. Attack on wage labor was constant. The slogan was, “Those who work in the mills should own them.” They opposed the degradation and undermining of culture that was part of the forced industrialization of the society. They began to link up with the radical agrarian movement. It was mostly still an agrarian society, the farmers groups that wanted to get rid of the northeastern bankers and merchants and run their own affairs. It was a really radical democratic moment. There were worker-run cities, like Homestead, Pennsylvania, a main industrial center. A lot of that was destroyed by force, but I again think it’s just below the surface, can rise easily again.

Next System Project: One of your overriding concerns has been imperialism. What do you see as the design principles that should be animating the internal features of a society that is no longer oriented towards militarism and imperialism? What might be some institutional characteristics for our communities, our economy and our national politics?

Noam Chomsky: Fundamentally, I think it again reduces to solidarity. In this case, international solidarity. Take something concrete: what’s called the immigrant crisis. People in Central America and Mexico, people are fleeing to the United States. Why? Because we destroyed their societies. They don’t want to live in the United States. They want to live at home. We should be acting in solidarity with them, first of all to certainly permit them to be here if that’s the way they can save themselves from the conditions that we’ve imposed, but also to help them reconstruct their own societies. Same is true in Europe. People are flooding Europe from Africa. Why? There’s a couple of centuries of history that explain that. It’s a European responsibility, both to absorb and integrate them, and to contribute to rebuilding the societies that Europe destroyed and that its wealth depends on.

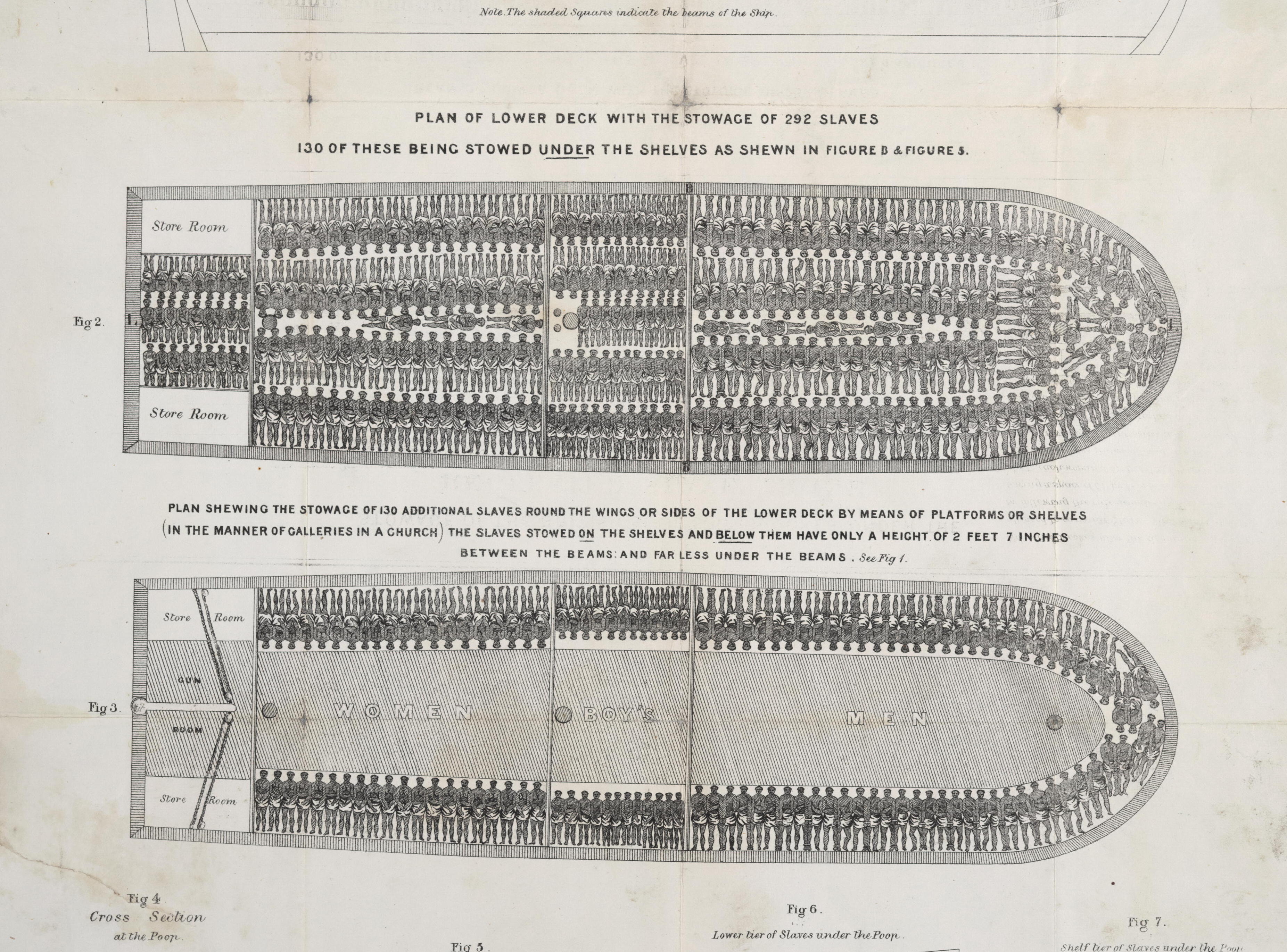

That’s true domestically as well. Take our own wealth and privilege: to a very large extent it derives from slavery—the most intensive, brutal slavery in history. Cotton was the oil of the 19th century. It’s what fueled the early industrial revolution—and the wealth and privilege of the United States, England, and others, depended very extensively on the horrifying slave labor camps in the United States that were imposing brutal torture to increase productivity of the commodity which enriched manufacturers. The main manufacturing plants were textiles plants originally. Textile merchants and commerce helped develop the financial system. The residue of it has never disappeared. Those are internal questions, which have the same character as imperial conquest and destruction.

Take, say, Africa. Parts of West Africa in the late 19th century were about in the same state as Japan. There was one difference. Japan wasn’t colonized, so it could follow the model of the industrial societies and become a major industrial society itself. That was blocked in the case of West Africa by imperial conquest. It may seem strange to think about it, but if you go back to say, 1820, Egypt and the United States were in pretty similar conditions. They were both rich agricultural societies. They had plenty of cotton, the crucial resource of that period. Egypt had a developmentally oriented government, pretty similar to the Hamiltonian system here, the developmental state. The difference was that the United States had liberated itself from imperial control. Egypt hadn’t. The British made it very clear that they were never going to permit an independent competitor in the eastern Mediterranean. Over time, Egypt became Egypt. The United States became the United States. That’s a lot of modern history; not all of it, quite a lot.

Those are things we should really think about.

The reaction to imperialist crimes should be recognition of them and compensation for them and solidarity with the victims. And this is not ancient history either. Take a look at the refugee crisis in Europe. Afghans and Iraqis are under horrible duress in Greek concentration camps. Why Afghans and Iraqis? Did something happen in Afghanistan and Iraq?