People and communities across the planet are suffering from an unrelenting burden of chronic disease, marine dead zones, toxic contamination, hunger, climate change impacts and wealth disparities. Western medicine uses the term inflammation to describe symptoms of heat, swelling, pain and loss of function. These are warning signs of an alarmed immune system, red flashing lights that our condition needs attention. One need not be a nurse or doctor to perceive from the daily news headlines or our daily interactions that modern life is grossly out of balance and discordant with how we are designed to exist. In many respects, we are experiencing systemic inflammation across global communities at a planetary level and we need an intervention. A shared sensing across the globe gives us insight and vital direction for next steps. What we can discover is a profound appreciation of the complexity and interconnectedness of life across traditionally silo-ed institutional spheres of influence—health care, economics, agriculture, and others—which can no longer be ignored. And while complexity and interconnectedness of planetary life forms may not appear to suggest a way forward, a model that incorporates these concepts is changing perceptions about what we must value and offers a vital opportunity to intervene and change direction.

Consider the 2016 World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Risks report, in which, for the first time in eleven years, four out of five categories —environmental, geopolitical, societal and economic — were featured among the top five most high impact risks to business. The report conclusion included the statements “Global risks remain beyond the domain of just one actor, highlighting the need for collaborative and multi-stakeholder action” and “We need clear thinking about new levers that will enable a wide range of stakeholders to jointly address global risks, which cannot be dealt with in a centralized way.” If we can appreciate that the predominant global business model has traditionally favored consolidation, supply chains, vertical integration and the externalization of social and environmental costs, these are bold and potentially transformational statements. Similarly, in anticipation of a looming global food crisis, the UN Agencies conducted the International Agriculture Assessment on Science Technology Knowledge and Development (IAASTD) to answer the question “What must we do differently to overcome persistent poverty and hunger, achieve equitable and sustainable development and sustain productive and resilient farming in the face of environmental crises? “ Their 2008 report, Agriculture at a Crossroads, highlighted the need to think systemically towards a revolution in agroecology—decentralized agriculture using ecological principles and local knowledge and input—and away from a highly consolidated industrial agriculture model. Their findings called for the distribution of benefits fairly and equitably through the food system, the support of democratic institutions and the recognition that the continued reliance on simplistic technological fixes will not suffice. The report was clear that business as usual is not an option. More recently, the 2015 Institutes of Medicine report, A Framework for Assessing Effects of the Food System, analogously concluded that, “systemic approaches that take full account of social, economic, ecological, and evolutionary factors and processes will be required to meet challenges to the U.S. food system in the 21st century.” While these findings are in stark contrast to the current global agro-industrial food system model, they represent the clarion call for a new ecological paradigm, consistent with the values and goals of the broad-based citizen-led Good Food Movement. Within health care, a similar holistic model is also taking root, as recent science in fields such as epigenetics, psychoneuroimmunology and the microbiome are helping us to better understand how influences such as stress, bacteria, exercise, spirituality, purpose and nutrition communicate with our genes and influence our health. The resiliency model, also known as a dynamic, integrative or whole person model of health, is consistent with how most individuals understand their lives and that our everyday health and well-being represent more than physical status, or the absence of disease, but include how vital we feel. Health is an interconnected function of emotional, mental, spiritual, and physical status. It is now widely recognized that clinical care determines only about 10% of health outcomes, while the confluence of community-derived social, economic and environmental drivers contribute the most to health outcomes. Moreover, the health care industry is now recognizing how the predicted health and infrastructure impacts of climate change threaten its future economic health.

Through these examples, an overlapping pattern and awareness of interconnectedness is clear. Across sectors, they highlight the limitations of our current mechanistic operating system and the shared, urgent, need to think systemically. This urgency reflects a similar hunger and impatience for a systems approach and value system within the many global citizen movements on climate change, food sovereignty and regenerative communities. Though the terminology may be unfamiliar, regenerative, holistic, integrative, complexity-based and ecological are terms that collectively embody the complexity of our relationship with one another on a living earth and the call for these values to be represented in our institutions and next systems. Health care is not immune to its own shortcomings, and these lessons enforce a reckoning with its underlying paradigm and how we more broadly rethink and even create health.

Thinking Differently

A significant challenge is that the majority of our institutions, including health care, have co-developed with an underlying economic paradigm which promotes growth and externalizes social and environmental costs in a manner that is inconsistent with health. Thus, thinking differently about health alone will not suffice. We will also have to untangle deeply enmeshed financial incentives within the business of health care, so as unlock the true health potential within us all. We enter this great transition with a biomedical model that has existed since the mid-19th century and has shaped modern medicine. The focus is on the physical properties of disease, too often overlooking issues such as social and environmental factors or belief systems. The result is a health care approach that focuses on disease and treatment without adequate consideration of relationship and the body as a complex, interrelated system. Over time, a variety of forces have conspired to facilitate a highly influential medical industrial sector with entrenched economic interests. Billing codes which determine reimbursement are copyrighted and licensed through a physician monopoly. Perverse financial incentives reward the treatment of symptoms, rather than root causes and health outcomes. Though the Affordable Care Act has begun to change these rewards, for most patients and providers, our health care system has transformed from a relational to a transactional model. Health has been commoditized. Providers are frustrated and are as dissatisfied with the system as patients, often experiencing significant burnout and moral distress. Both are yearning for a satisfying relationship, necessitating more than a twelve-minute visit.

For many families, health care remains financially inaccessible. With health care costs averaging over $9000 per person, the population of a small city of 100,000 spends just under one billion dollars per year for health care. The financial cost to people and their communities is burdensome, and has become a shell game of shifting responsibility, robbing the budgets of households, businesses, schools and local governments. Though total health spending is the same, as a nation, we spend far more on health care and far less on social, economic and environmental drivers of health relative to other countries, with comparable health outcomes, Rather than working to address root causes of health, we rely on a health care system for those that can afford it, to pick up the pieces. This knowledge does little to help a family with health care bills trying to make ends meet, but it helps us understand where we should focus our efforts and resources if we want to reduce health care spending and more equitably influence health outcomes. Yet, before asking where we want to spend our money on health, what if we asked how we might create a system in which health was built in instead? This question requires us to rethink our health care model, our definition of health and the creation of a new health operating system.

Complex Systems, the Commons and the Next Operating System

When discussing complex systems, it is important to define the key underlying principles, incorporating the recognition that all of the systems we are discussing—human health, economics, health care, global ecology—are complex dynamic systems. Complexity science gives us important insight as to how a systems worldview changes our perception:

- From parts to the whole

- From objects to relationships

- From knowledge to contextual knowledge

- From quantity to quality

- From structure to process

- From contents to patterns

As a result, we emphasize new paradigm styles and organizational characteristics. These would embody approaches and attributes such as collaboration, networks, fluidity, empowerment, self-organization, transparency, flexibility, evolution, adaptability, listening, and connection rather than hierarchies, autonomy, self-preservation and control. Systems thinking helps rebalance scientific knowledge by re-valuing cultural and other knowledge allowing for a diversity of expertise from a diversity of experiential contexts. Through a shift in value from quantity to quality, an entirely new set of metrics beyond cost becomes important. As we imagine health care of the future, these values and features will be essential. We can draw on principles of the “commons” which explain how communities have worked together successfully to craft, monitor, enforce, and revise rules to limit their behavior and keep their resources available for the long term. At their core is an acknowledgement of the importance of an approach that has a fair set of rules, a means to represent a voice, transparency, self-determination, localized boundaries or a sense of place, inclusivity and the right to health and well-being.

Though the public debate on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has largely focused on its ability to provide affordable health care access, many less familiar but equally important provisions are helping incentivize new paradigm concepts and rules. These requirements provide a means to experiment and facilitate the emergence of next paradigm models and approaches and include: incentivize and/or require multi-stakeholder collaborative processes (e.g. Accountable Health Communities models and Community Health Needs Assessments [CHNA] requirements), increased transparency (e.g. pharmaceutical marketing), an expanded definition of health care workforce, value over volume , workforce diversification and a focus on the multiple social, environmental and economic drivers of health. Collectively, these approaches have put into motion the opportunity to rewrite financial incentives and broaden stakeholder involvement in decision making, most notably from the community. While still a work in progress, the ACA has introduced vital holistic approaches and concepts that usher in the beginning of the great transition in health care and how we define health.

The Next Health System

As we move forward, we must keep in mind that these issues are complex and require ongoing experimentation to test and probe the potential of nascent models and approaches. This uncertainty is challenging for our culture, which is accustomed to long term planning and the belief in predictability, especially in the context of impending climate change impacts. Moreover, we are accustomed to working within silos of expertise and have undeveloped interpersonal tools to work in this new networked, relational space. We must incorporate commons principles and subsidiarity in the context of a strong national and global rights framework. Nevertheless, across the globe, a variety of players are evolving their own principles of health creation. For example, through a rich stakeholder process, the United Kingdom National Health Service has co-created a sustainable route map, which includes a desired set of destinations and outlines key components of the next health system. While the concepts are applicable to diverse communities, it is clear that no centralized path forward can show us the right way for all communities. However, the following are a variety of components, foundational to the emerging next health system framework.

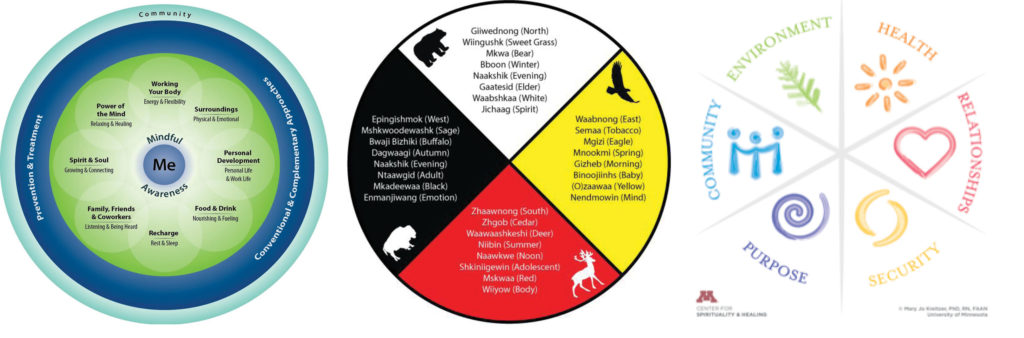

1. Whole Person Model of Health

As humans are complex systems in relationship with complex environments, it is logical that we consider human health holistically. Astonishingly, health care still utilizes the medical model, a mechanistic approach in which the focus is on the disease, rather than the individual as a whole. While appropriate for acute care and surgery, the result is an over emphasis of bio-physical processes at the expense of the many other well-established interacting influences on overall health and well-being, such as strong relationships, sense of purpose, toxic exposures, the ability to affect change, spirituality, clean water, access to nutritious food, etc. As this study from the Netherlands illustrates, a dynamic model is closely aligned with the general public’s understanding of health and nurses as health care stakeholders. And, as we begin to explore policy options that incorporate health, it is worth noting the disconnection between the general public and both policy makers and physicians, whose perspectives diverge most strongly from the holistic model of health. The old mindset of health as strictly physical is deeply locked in our zeitgeist. As a result, it challenges our ability to fully link drivers of poor health such as unsafe housing, discrimination, poor food access, toxic exposure, loneliness and low job security to overall health and well-being. The old paradigm also tends to place a lower value on community health, environmental health, nutritional health, spiritual health, and mental health. Because the standard attitudes about health prevents us from adequately discussing health with policy makers, the devaluation of these key upstream drivers of health hampers our ability to make systemic transformation consistent with the needs and values of community. Alternatively, a holistic model must by definition include all the mental, physical, emotional and spiritual dimensions of health. At its core, the whole person model emphasizes resiliency and supports and promotes one’s ability to actually thrive. Through this change in perspective and priorities, we can start to imagine how a truly healthy individual might look and feel. And we can imagine the types of neighborhoods, communities and work environments that would support and facilitate flourishing individuals. The whole person model requires measures that are both qualitative and quantitative, which are far more expansive than our traditional bio-physical measures of health, such as blood pressure, and include measures such as career satisfaction, adequacy of financial resources, community support, in addition to a sense meaning and purpose. Importantly, by including these multiple dimensions of health in health assessments, it allows us to better quantify and link upstream drivers to health outcomes and develop effective strategies. We can see glimpses of the future already. HealthPartners, a large Minnesota based cooperatively-owned health plan and health provider, utilizes and advocates for these summary measures of health and well-being and explains the health rationale for well-being in all policies. A whole person model has been adopted and fully implemented by the Veteran’s Administration. As a systems model, the whole person model is foundational to our next systems. In order to unlock our full human potential, the holistic model must be incorporated into the DNA of our medical, nursing and other health professional training, our health systems and our broader culture. Following are representations of the whole person model, also called well-being, holistic or whole health.

2. Integrative Health and Medicine

Integrative health and medicine (IHM) is a newer operating system that has been emerging as our focus shifts from disease to the whole person, While IHM is sometimes confused with specific health professions or disciplines (functional medicine, naturopathic medicine, chiropractic, Traditional Chinese Medicine, homeopathy, etc.) it is the holistic style of considering an individual within the broad context of body-mind-emotions-spirit that describes integrative health and medicine. Rather than focusing merely on the eradication of symptoms, IHM works to address underlying causes, utilizing a whole person model of health. As a holistic approach, IHM incorporates diverse spheres of evidence-informed knowledge from within a multitude of disciplines, healing traditions and therapies that deeply emphasize lifestyle as the foundation to health and expands the healing toolkit well beyond pharmacological approaches. As a relational approach focused on supporting resiliency, IHM empowers the patient or client as a partner, helping to foster agency and self-efficacy, while recognizing how an empathetic approach itself can improve health outcomes. It is no surprise that IHM is rapidly gaining prominence in the general public and by health providers because it offers a relational model between provider and patient, and satisfying life affirming and healthy treatment options. By supporting the whole person and addressing the complexity of root causes, rather than focusing on the suppression of symptoms without actually restoring health at the same time, IHM allows providers to return to the joy of practicing both the art and science of medicine and health care.

In the midst of skyrocketing pharmaceutical costs, a variety of studies demonstrate the effectiveness and cost efficacy of integrative medicine. Additionally, in the context of a national opioid epidemic, IHM offers meaningful tools to treat chronic pain and depression. As health care is a significant climate change contributor, we must also recognize that despite the focus on the energy required by buildings and transportation, the health care pharmaceutical footprint is larger than that of building energy and many of these drugs move into our waterways with a host of ecological impacts and potential adverse health effects. We clearly need pharmaceuticals, but we must also illuminate expanded alternative options that allow us to use drugs more judiciously. Organizationally, a holistic approach facilitates the development of multi-disciplinary teams and a new workforce of support from professionals such as “promotoras”, health coaches and community health workers who bridge and integrate community members with health care expertise. Increasingly, group visits are being employed, demonstrating the power of collective support and the appreciation by providers and patients alike. Health systems such as Allina Health and the Cleveland Clinic are now advancing IHM into their health systems, incorporating multiple disciplines, group visits and various therapies which demonstrate increased value and/or decreased costs overall. Similarly, we can now find IHM in community health centers and free clinics across the country while the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health includes the majority of major health systems and academic centers across the country. Understandably, the IHM approach and the whole person model of health is perceived as a significant disruption to the financial interests of an entrenched medical industry and traditional spheres of influence. IHM offers patients agency, highlights root causes outside of the traditional domain of bio-medicine, reduces a strict dependence on pharmaceuticals and other medical treatments and technologies, is inclusive of diverse professional disciplines and emphasizes a collaborative model. IHM embraces and includes allopathic medicine, and is an expansive relational approach to health and well-being. IHM is integral to the next health system and like the whole person model of health, it must be woven into our culture so that we broaden our definition and catalyze a new narrative of health that focuses on resiliency and a living systems model.

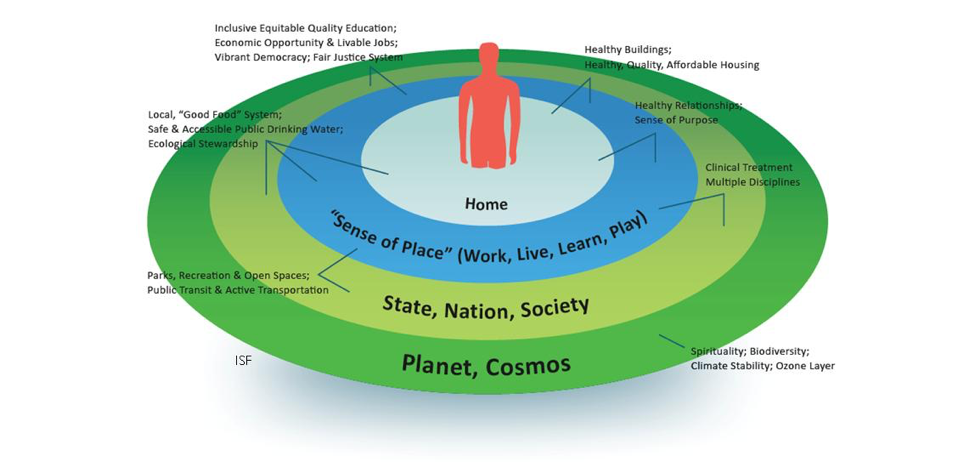

3. Health and Place

If we fully appreciate the surprisingly limited influence of health care on health, the locus of health shifts from our hospitals and clinics to the individual as a whole person, in the context of place. With this new lens, our health becomes place-based, meaning that where we routinely interact on a daily basis—our homes, neighborhoods, places of work and worship and our schools—determines our health. In other words, our health becomes indivisible from that of our community and is a shared community responsibility. We look to our natural environment and its many facets as nourishment, water and air as our life support system. Therefore, our health is a function of place in the context of nature, or environment. In many respects, we are relearning lessons from an array of indigenous cultures in which this concept has been long understood and incorporated into the values and operating principles of their communities. Access to affordable, quality health care is critically important, and particularly vital when treatment and support are needed. However, in examples such as Kokua Kalihi Valley where health care includes the empowerment of communities to become whole through job opportunities, local cultural activities and food access, we shift our conception of both health and the role of health care. We begin to see how investments in safe and stable affordable housing positively influence health outcomes and are a function of place. In a national survey of primary care providers and pediatricians, 85 percent believe that unmet social needs—things like access to nutritious food, reliable transportation and adequate housing—are leading directly to worse health for all Americans. This helps understand where we must invest as a society and it broadens the responsibility to include all community actors—government, education and business. In a variety of states, such as Minnesota, we are beginning to witness a shift towards shared responsibility for health with many examples and opportunities to build health into all policies.

Functionally, the role of place requires health care to examine its role as anchor institutions and understand how its endowments, purchasing and employment practices can be leveraged to support the economic, social and environmental health needs of their communities. In addition, place opens the potential for collaboration with otherwise competing hospitals, health plans, local business and other community partners, an approach incentivized through the Affordable Care Act’s, Accountable Communities for Health (ACH) model.

One major hurdle within the evolution of place based models is the desire for local decision making and global budgeting over health spending. Maryland provides a petri dish for experimentation resulting from a unique state agency which sets payer reimbursement rates, thus allowing for some predictability in financial forecasting. This model has facilitated the development of a place-based global budgeting prototype with pre-established value-based benchmarks. With several years still to go, the model is providing promising results, including decreased costs, increased value and increased upstream investment.

4. Living Systems and Democratization of Health

As we have described, the medical model has facilitated the evolution of hierarchical health care systems disconnected from the communities they serve. To fully reflect the needs and values of the community, health care requires a restructuring and “democratization” of health care and health.

While we have already mentioned the ACH model, the Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) is a legal requirement for hospitals to engage their communities and develop a plan to address health needs every three years. The CHNA is an important new tool that requires health care institutions to focus attention towards community needs and upstream drivers of health. This dialogue is long overdue, as hospitals and communities have historically had little experience in working with one another and the bio-medical model is not yet fluent in the vernacular or concepts of the whole person model. Ideally, these processes will build shared awareness about potential upstream investments and resources, and will transform community actors into powerful advocates for policy and systems change beyond a bio-medical lens on issues such as affordable housing, healthy food access, livable jobs, paid sick time, public transit, and clean water/air. The CHNA process is helping to shift community mindset from consumers of health care services to active agents of change over the health of their communities. The CHNA is also forcing a slow appreciation for different types of expertise beyond bio-science, highlighting uneven power dynamics and the need for collaborative operating styles and the development of new metrics and a language of health that is inclusive of community perspectives. This type of work requires participatory leadership styles and relational skills that open minds and open hearts, such as those offered through the global Art of Hosting community of practice. Many community actors still remain unfamiliar with the CHNA process. Skills training for working in group processes is clearly necessary. Nevertheless, the CHNA is important for building an essential community voice into health care and it begins a necessary dialogue, relationship building and a shared approach to health. Ultimately, a health care system that works for everyone must include an ongoing process to include the voice of and to be accountable to the community.

Other means to include community and/or employee perspective are the many cooperatively owned and managed clinics and medical facilities, such as the Minnesota based health plan Health Partners. It is estimated that the number of people served by health, wellness and social services co-operatives world-wide exceeds 300 million. Within the UK, social enterprises called Community Investment Companies provide a wide range of services, including elder care and music therapy. Gather in Circle was established to provide training for communication in collaborative spaces, an essential skill for how we will need to work in the new economy. One of the most exciting health care models operating in the new paradigm is the Nuka System of Care. This internationally recognized model, based in South Central Alaska, was completely redesigned several years ago, moving from a centrally organized bureaucratic system to customer ownership and control of the health care system. Designed around Alaska Native values and needs, the vision and mission is holistic—a native community that embraces physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellness. Operational principles are based on relationships, with an emphasis on wellness of the whole person, family, and community. They have successfully fostered an environment for creativity, innovation and continuous quality improvement. Nuka System of Care brings the foundational understanding that health is a longitudinal journey across decades in a social, religious, family context and highly influenced by values, beliefs, habits, and many ‘outside’ voices. As a result, a patient with congestive heart failure and pulmonary disease might have a primary diagnosis of insecurity, loneliness, confusion and anxiety with interventions of behavioral changes and the understanding of primary motivators.

Ultimately, whether through ownership models, the CHNA process, or ongoing engagements processes, health care must develop a means to reflect the values, the needs, the diversity, the complexity and the design of the local community.

5. Health, Environment and Rights of Nature

Ecological feedback loops and new science remind us that we are part of nature, not separate stewards with dominion over the natural world. The human microbiome, whose genes outnumber our own multifold, is linked to host of human conditions including cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and depression, and is in relationship with our external environment through our interactions with animals, soil, food, the air we breathe and one another. Our health is in relationship with climate, food supplies, and clean water—all of nature providing basic human needs. Epigenetics helps explain how toxic chemicals modify gene expression. Through a bio–psycho–social scale, we can measure Solstalgia, a sense of distress when valued environments are negatively transformed. Moreover, nature has intrinsic healing properties; a room with a view of nature decreases the duration of a hospital stay. While Nature offers spiritual, physical, emotional and mental dimensions of health, climate change is forcing us to fully appreciate our intimate relationship with nature.

As we co-evolve an economic system which fundamentally internalizes environmental costs and fully accounts for natural capital, because of its substantial ecological footprint, health care has a moral obligation and a responsibility to act and lead. Conservatively, health care endowments are estimated to be about $500 billion dollars, which can be redeployed to support cleaner energy, invest in social enterprises or otherwise align capital to support whole health. Marketing budgets of hospital systems, which can be ten times higher than their entire food service budget, can be reallocated to further support food access and nutritious food from sustainable food systems. Through Health Care Without Harm, the campaign for environmentally responsible health care, a wealth of tools and resources have been created over the last twenty years to help health care leadership and health providers align health and ecology. A variety of health care systems are now helping lead this transformation, including SSM Health and Dignity Health, which recently announced their divestment from coal. Kaiser Permanente, a national environmental leader, has a bold climate and environmental agenda. As the majority of environmental impacts fall disproportionally on the poor and on communities of color, the hierarchy of human value built into our economic system is glaringly obvious, indelibly linking environment and justice. Equally obvious is the hubris in placing humanity above other species. These inequities inform us that our collective success will come about when we see ourselves are part of the community of nature. Similarly, the allure of perpetual health and life through expensive life extending technologies tends to deceive us into believing we are separate from the natural cycles of decay. Initiatives such as the Sacred Art of Living & Dying are training health professionals and care givers in the skills of emotional and spiritual wellness that we once collectively held in community.

As we transition, we must build and expand place-based regenerative prototypes such as the Egyptian based SEKEM or The Food Commons in Fresno California. And we can learn from the bold conceptual initiative Buen Vivir, in Ecuador and Bolivia, in which the Rights of Nature and the Right to a Good Life are constitutionally enshrined.

Conclusion

Many of our major challenges are a function of linear models and associated hierarchical structures, with operating systems whose shortcomings are becoming broadly apparent as we extend our reach far beyond our planet’s ecological carrying capacity. Health and health care are in the midst of a radical redesign as a new and necessary ecological worldview emerges and takes form. Policy makers, business leaders, clinicians, community organizations and others are now coalescing around a new vision of health. Rather than relying on the traditional bio-medical model for our understanding of where and how we derive health, this new vision embraces an interconnected place-based holistic framework of health and well-being. This framework is helping to elevate the awareness that many of the cultural systems in which we have relationships—economic, educational, food, judicial, etc—are a reflection of an underlying historical narrative, or collective belief system of human values. We can now see how these built in hierarchies connect to the wide ranging environmental health disparities, health inequities within our health care systems and ecological ruin; they must be deconstructed. Economic growth cannot continue unabated and we must reorient our operating system to one that is regenerative and consistent with an ecological model and earth’s ecological processes. What we are uncovering is ancient learning from indigenous cultures, and from which we all are rooted. The health and well-being of individuals is inseparable from nature and inseparable from the health of community. Our job is to put ancient knowledge and traditional wisdom into right relationship with science and technology.

While we have become accustomed to prescriptions and direction by experts, the answers lie within an iterative process of experimentation and relational models. We all have expertise to offer. Though operating without a clear set of instructions can feel daunting, the transformative models that our generation is called to design requires a new operating system, a new way of being. This new consciousness itself is the foundation for the next health system. This generation is prepared to build on the many aforementioned examples. We can feel confident that intention and action will naturally emerge as we reconnect to our consciousness and inner purpose as whole beings on a living planet.