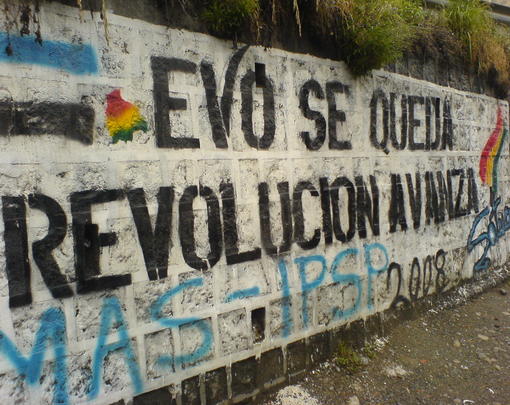

As part of Latin America’s then-growing “pink tide,” Rafael Correa and his Alianza País party came to power in Ecuador in 2006 in what Correa often called a “citizen revolution.” In office for ten years, Correa became the country’s longest-serving president, providing a modicum of stability in an often-turbulent political arena. His tenure was marked by progressive fiscal policy, significant reductions in poverty and inequality, and the recognition of collective rights and the rights of nature, but was also mired by continual clashes with both the political right and many of the very social movements that brought him to power.

The Correa years present ample material for the study of the relationship between social movements and the state and underscore the question of what is gained or lost when radical change is pursued through the existing structures of the state. This essay aims to explain and examine some of the most innovative policies and practices that have emerged during this period and their relative success in the context of a decidedly top-down approach to revolution. Those initiatives examined will include transformative macroeconomic policy and a citizen-initiated project to build the framework for a “social knowledge commons”.

President Correa’s election was possible largely due to a long history of indigenous organizing and hard-bought coalitions between social movements and leftist political parties. The 1980s and 1990s had seen waves of neoliberal economic reforms, such as trade and financial liberalization, spending cuts, export promotion, and privatization of state-owned industries. Together, they left Ecuador deep in debt to foreign (mostly US) investors and economically dependent. Ever worsening economic conditions culminated in a severe economic crisis in 1999 that led then-president Jamil Mahaud to adopt the US dollar as Ecuador’s official currency. Subsequent protests precipitated his ouster, making Mahaud one of seven presidents who came and went in a decade marked by corruption scandals and increasing distrust of the ruling class.

Correa, Ecuador’s first economist President, a former Minister of Finance, seemed well placed to turn things around. But in his first years in office, some of the very indigenous organizations and social movements that helped him win the election became some of his biggest detractors, citing cooptation of their agendas, attacks on civil society groups, and continued environmental destruction owing to dependence on natural resource extraction.

After taking power in 2007, Correa presided over a Constituent Assembly that crafted the 2008 Constitution, at the time hailed as the world’s most progressive.1 This new constitution returned control of nonrenewable natural resources to the state, provided the framework for political participation at all levels of government, created citizens’ oversight councils, and— for the first time anywhere in the world— codified the rights of nature.

Forming such a Constituent Assembly to develop the new constitution had been a key demand of indigenous social movements and political parties. Although many were disappointed to see Correa’s Alianza País party taking the vast majority of seats, the new constitution shifted the country significantly to the left and provided a platform for the popular new government to launch a host of new programs.2 Collective rights, food sovereignty, respect for diversity, and even support for the solidarity economy were all enshrined in the 2008 Constitution. Despite these gains, the story of the Correa years remains for many a story about the gap between the vision and ideals of the 2008 Constitution and its uneven application.

In 2009 and 2010, nationwide protests and strikes broke out around large-scale mining practices and proposed land and water regulations that would indigenous groups claimed had not properly followed prior-consent practices. Many in social movements had hoped that the Correa government would curtail natural resource exploitation and were angered when it did not. The ever-deepening animosity exploded in 2013 when Correa issued Presidential Decree #16, which regulated the operations of all social movements through a new Social Organizations Unified Information System, requiring all to register and report detailed information on their finances and activities to the government. Within two years, the Correa administration had used the decree to rescind the legal status of prominent environmental organizations and to boot the popular indigenous coalition, CONAIE (National Congress of Indigenous Organizations of Ecuador), out of its offices. Such actions only solidified a growing belief among many activists that the decree was part of a larger attempt to limiting the social movements to government-friendly groups.

The left never united behind Correa and policies like the decree further alienated some of his initial supporters. That said, no viable alternative emerged from the left either. When the Popular Democratic Movement (MPD) banded together with Pachakutik (CONAIE’s electoral arm) to run candidates in the 2013 elections, the coalition garnered only 3.3 percent of the vote and lost seats in the National Assembly, likely due to their collaboration with elements of the political right.3

Today, Correa’s Alianza País party remains largely at odds with indigenous organizations (including Pachakutik). The two camps have clashed over everything from proposed water regulations to Ecuador’s entry into ALBA (the Bolivarian Alliance of the Peoples of Our Americas), a Venezuelan-led regional trade block.4 The indigenous coalitions and their national and international partners have repeatedly taken to the streets to protest Correa’s extractivist policies—vilifying him for backtracking on the high-profile Yasuní ITT initiative5 and for criminalizing protest. In 2016, Pachakutik refused to support the 2016 Presidential campaign of Correa’s former Vice President, Lenín Moreno, though in the end he did win by a slim margin.

Distinguished Ecuadorian scholar Marc Becker points to the constant clashes between Correa and Ecuador’s social movements as evidence of “the complications, limitations, and deep tensions inherent in pursuing revolutionary changes within a constitutional framework.6 Although Correa rode into power on the heels of social movements, once in he took a top-down approach to change.

Whether this type of approach will ultimately succeed and stand the test of time is not yet known. But early lessons from some of the most interesting innovations of the Correa era are emerging and can inform future attempts at state transformation.

The politics of participation

Initial excitement about profound progressive change in Ecuador seemed well-founded since the 2008 Constitution provided the framework for a more democratic, participatory and pluralist government and a more equitable economy. The 2009 Ley Orgánica de Participación Ciudadana (the Fundamental Law for Citizen Participation) codified the inalienable right to participate in Ecuador’s democratic process at all levels of governance and paved the way for new citizen assemblies and sectoral councils. Citizens assemblies can be formed on their own and function to advance development plans and local policy initiatives, which they share with local representatives in order to achieve their full adoption. Meanwhile, the sectoral councils correspond to each government ministry provide forums for direct participation in dialogue, deliberation, monitoring and evaluation of public policy.

The 2009 law further directed the National Development Council to convoke a Citizen Assembly of the Plurinational and Intercultural State. Here, dialogue and direct consultation between the state and its citizens drives the creation, approval, and monitoring of the National Development Plan—basically, the government’s political program.7 Subsequent decrees and laws expanded such participatory mechanisms and instruments as popular amendment, popular consultation, popular recall, repeal of legal regulations, and decentralized governance.

Before 2008, popular recall had applied only to local officials and members of the national legislature. But the new constitution enabled citizens to revoke the mandate of any elected official at any level of government—including the presidency—by a popular vote. The statute on popular consultations and citizen-initiated referenda was also amended to allow the national legislature to invoke a popular consultation in cases regarding natural resource extraction, an area where it was previously not allowed.

Tools for participatory democracy also became more agile thanks to the 2008 Constitution. For example, the threshold of votes needed to pass a referenda or popular consultation is now the absolute majority of valid votes, rather than of valid voters. In like vein, the percentage of voters needed to initiate a popular consultation or popular amendment process was also reduced.

Constitutional amendments passed in 2014 (with Correa’s Alianza País party in control of the Parliament) granted the government much greater control of the media and allowed for infinite re-election of the President. Maligned by human rights groups around the globe, the new media restrictions allowed the government to censor outlets that it deemed had not presented “verified” and “precise” information and prohibited “censorship,” defined as the media’s failure to cover an issue government considers “of the public interest.”

The use of executive power to overrule the people’s desires as expressed in popular plebiscites was seen by many as further proof of the consolidation of power at government’s highest levels. Most famously, the National Election Commission’s 2013 rejection of the request for a plebiscite on the Yasuní initiative, for which a coalition of environmentalists and indigenous groups had gathered over 700,000 signatures, deepened distrust of a government avowing support for participatory democracy. The Election Commission rejected nearly two-thirds of the signatures collected so the number of valid signatures fell below the trigger point for a plebiscite. Angry demonstrators took to the streets alleging fraud, accusing the Election Commission of bowing to the President’s wishes after Correa spoke out openly against the attempt to invoke a plebiscite and warned the public that the petitioners would fail.

On balance, it seems, the Correa administration considered a top-down approach the only one powerful enough to consolidate and institutionalize new policies and practices while attempting a socialist revolution through the existing state apparatus. According to some scholars, “all organized groups, regardless of their ideology or class, ‘were dismissed as privileged interlocutors representing special interests, while [Correa’s] elected government was deemed the only legitimate guardian of the national interests.’”8

Even some of those who worked closely with Correa in his government complained about his administration’s top-down approach. A member of Correa’s Ministry of Finance, Pablo Dávalos, said that “the new political system is more vertical, more hierarchical, and more dependent on the president than before,” a sentiment echoed by other dissenters over the years. By closing off space for opposition—both from the Right and from within the Left—Correa assured the approval of many of his initiatives while maintaining a populist discourse.

Macroeconomics and the top-down approach

In many ways, the greatest advancement in Ecuador directly attributable to the Correa administration is its macroeconomic policy. Despite a continuing but unsustainable dependence on oil revenue, the Correa administration’s policies have boosted economic sovereignty and stability more than those of the neoliberal administrations that preceded it did and also significantly reduced poverty and inequality. While certainly a top-down process, the government’s macroeconomic approach seems to have consolidated several gains in the path towards greater equity and sustainability in the Ecuadorian economy.

Furthermore, Ecuador managed not only to weather the storm of the 2008 financial crash, but was able to actually increase social spending and reduce poverty—quite a feat for a dollarized economy heavily dependent on one principle commodity (oil).9 Indeed, from 2006-2016, Ecuador’s poverty rate declined by 38 percent and the rate of extreme poverty by 47 percent while inequality also decreased.10

These gains are due, in part, to a set of reforms to the financial sector that allowed the government to increase social spending substantially. From the very day he took office, Correa openly broke with the mainstream economic thinking, and the new constitution he ushered in undergirded a new economic order in Ecuador. It re-nationalized the central bank. It also redefined the financial sector to include popular and solidarity-based economies fueled by credit unions, cooperatives, and savings and loan associations.

Other financial reforms followed. After declaring its international bond debt “illegal” and refusing to pay some $30 million in interest on the country’s remaining debt, the government set its sights on the banks. Correa taxed capital leaving the country and required banks to hold 45 percent of their liquid assets domestically (later increased to 60 percent).11 Banks and other financial institutions were also required to contribute to a liquidity fund so that in any future financial meltdown they could bail themselves out rather than turning to the government.12 Correa also required banks to hold 3 percent of their total deposits in the Central Bank and/or public bonds or financial institutions.13

These new taxes on banks and the revenues generated by wiping out various tax and other exemptions were directly funneled into the country’s conditional cash-transfer program, the Bono de Desarrollo Humano (the Human Development Bond), and used to increase government’s monthly payouts to its most vulnerable populations. In further relief to the poor, the government also removed financial institutions’ charges on checking and savings accounts and lowered ATM fees.14 Thanks partly to these fiscal policies, the Correa administration was able to make its promised investment in the social sector, doubling spending from 2006 to 2011, and “making substantial investments in public education and health.”15

To bolster the solidarity economy, the government created a National Program on Popular Finance, Business and Solidarity Economy (Programa Nacional de Finanzas Populares, Emprendimiento y Economía Solidaria or PNFPEES16 ) The aim here was to strengthen and grow the solidarity economy by offering training, technological transfer, and lines of credit.

PNFPEES met that goal. By 2011, Ecuador had over 1,000 cooperative banks with $1.5 billion in assets and 2 million members.17 And by 2014, the CNFPS had lent over $600 billion to co-ops and credit unions, allowing them to significantly increase their lending.18 In all, the popular and solidarity economy sector accounted for one quarter of Ecuador’s assets by 2014.19 By the time government crafted its 2013-2017 program, fully 30 percent of government procurement was directed to the popular and solidarity economy.20

Correa’s government also challenged conventional economic thought by implementing a form of quantitative easing (introducing new money into the money supply through a central bank) even though the country does not have its own currency.21 Until Ecuador pursued these policies, the conventional wisdom was that making another nation’s currency your only official currency robbed you of the latitude needed to use such fiscal policy instruments like quantitative easing. However, Ecuador managed to do it twice, creating a grand total of $6.8 billion new dollars. From 2011-2013, state-owned banks issued a total of $1.7 billion in bonds, which the state-owned Central Bank bought on the primary market and used to buy government bonds or to make loans to the private sector. The remaining $5.1 billion was issued as government bonds that the Central Bank bought directly from 2014-2016.

Ecuador achieved another monetary first, too. In 2014, it developed the world’s first state-run electronic currency, which is transferred over cellphones, ATMs, and websites. Although e-currency is backed by liquid assets in the country’s official currency, the Central Bank could ostensibly issue new money that is not backed by those dollar reserves.22 According to the government, electronic banking is cheaper than traditional banking, which gets caught on the costly treadmill of exchanging deteriorating U.S. bank notes for new ones.23 In the financial world, however, many view e-currency as a contingency plan or a step toward de-dollarizing the Ecuadorian economy, an allegation the government vehemently denies despite Correa’s public disdain for adopting the dollar in the first place.24

Besides reducing poverty by making money transfers free and expanding access to financial services to those without them, this Sistema de Dinero Electrónico (Electronic Monetary System) is likely safer. Not having to carry or keep significant amounts of cash around especially benefits taxi drivers and shop owners. And though the electronic currency was slow to catch on at first, after the “Solidarity Law” was passed in July 2016, reducing the value added tax on electronic transactions (both through credit cards and the electronic currency), use has been rising. In May 2017, the Central Bank reported, there were over 300,000 electronic currency accounts and by then there had been more than $31 million of transactions in the currency.25

Despite continued dependence on oil and other primary material exports, Ecuador’s economy remains more stable than many of its other “pink tide” neighbors. Nevertheless, only continued economic diversification can ensure the economy’s long-term stability and consolidate the equity gains of the Correa years. Whether additional progress may have been possible had a more participatory approach to economic planning been taken remains an open question.

Open Society/Knowledge Commons and the bottom-up approach

Apart from macroeconomic policy, one of the other most innovative and potentially transformative initiatives of the Correa years came from the grassroots. The fact that this project was not initiated or controlled by state forces themselves may have contributed to its lack of initial uptake, though it appears that some of the work has slowly become more institutionalized by the State, albeit without much interaction with the groups that initiated or participated in the larger process.

That initiative, the Free/Libre Open Knowledge (FLOK) Project aimed to lay the groundwork for the creation of a national knowledge commons that would include everything from open software to seed banks to free access to scientific research and the creation of a university based on open knowledge principles. An international collaboration, this pioneering project sought to sow the transformation of whole sectors of the Ecuadorian economy, moving it from its capitalist extractivist roots and dependence on foreign investment to an inclusive commons-oriented and sovereign model.

The project idea was inspired by the Correa government’s first five-year strategic plan, published in 2009. To free Ecuador from dependence on primary sector exports, the government laid out a strategy for transforming the “productive matrix” of the country to a “democratic and inclusive model based on the knowledge and capabilities of all Ecuadorians,”26 thus allowing greater national sovereignty. This new way to create economic independence would also foster participatory democracy.

In a 2013 interview, FLOK team member Daniel Vazquez recalled the program’s genesis:

In 2012 a few members of aLabs, a free software company, were in Quito, Ecuador when Julian Assange solicited asylum at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. When the government responded positively, those individuals contacted The National Institute of Higher Education (IAEN)…[which] shared with them the Secretary of Science, Technology and Higher Education’s vision for changing Ecuador’s productive matrix and his strong belief that Ecuador needs to become a “paradise of knowledge.”…We created a proposal for an investigative process that would be carried out in conversation with the Ecuadorian public and the local, regional, and international scientific communities. At the end of the process, our goal [was] to create ten “base” documents from which policies can be drafted to enable Ecuador’s transition to a shared and free knowledge society for industry, education, scientific research, public institutions, infrastructure, etc.27

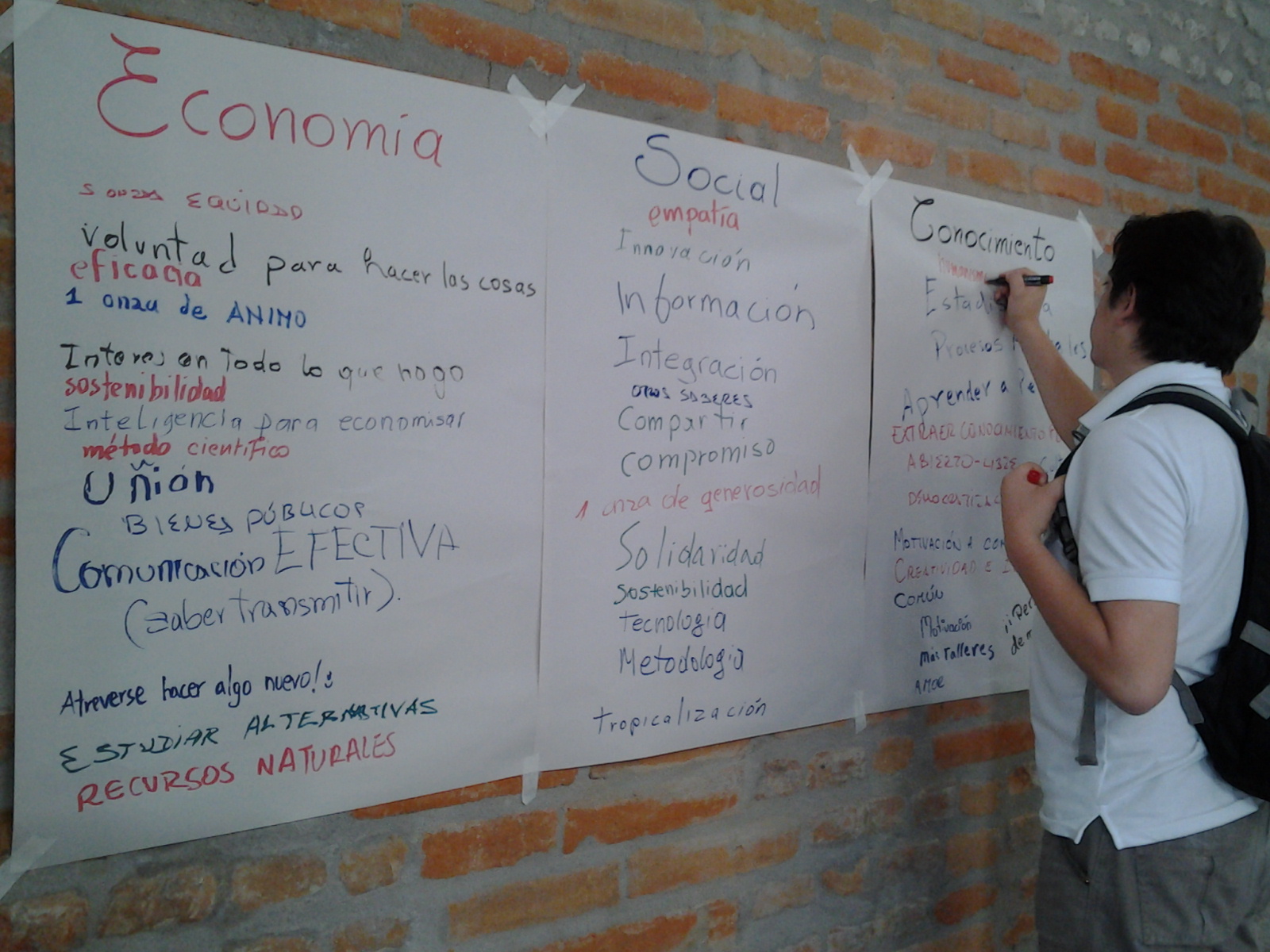

In 2013, a group of Ecuadorians and international counterparts began exploring the legal frameworks and societal processes needed to create a commons-oriented economy based on free and open access to knowledge. In an initial show of support, the Ministry for National Planning and Development, the Ministry for Innovation and Human Resources, and the National Institute for Advanced Studies invited a cadre of international experts to create a participatory process for developing a strategy for transitioning to a “social knowledge commons” society.28

The two-year process included a research phase and a participatory, collective Buen Conocer Summit in which over 200 people participated. Twenty-four workshops were held around the country to solicit the perspectives and contributions of diverse Ecuadorians. Journalist and media activist Bernado Gutiérrez, head of communications for the project, believes the process created an “academic and activist ecosystem,” partly by mapping current initiatives and identifying areas for future development.29

The FLOK project culminated in a Commons Transition Plan and more than a dozen legislative proposals.30 Some 1,500 people participated in planning in one way or another. Although some project leaders now decry the lack of follow through after the summit, others hail the open, collaborative process itself for introducing new practices and ideas into the broader Ecuadorian community.

The proposals that came out of the FLOK process include cover a wide range of potential economic and social policies and programs. Among them are the creation of a community-managed investment fund for organic farmers; publicly funded seed banks; rural hackerspaces; open manufacturing; and the release of all publicly-funded R&D under free licenses.31

FLOK’s organizers seemed disappointed that few of these recommendations have been implemented within Ecuador after the Buen Conocer Summit. But a few concrete achievements have been made and should be recognized. In 2014, Ecuador mandated that all texts used by the academic community, including books and lecture notes, be made available for free on the internet under Creative Commons licensing. Since 2014, Ecuadorian scientists have been developing an open source passenger boat, powered entirely by renewable energy, to service Ecuador’s remote Galapagos Islands.32 And in March 2016, Ecuadorian government agencies started transitioning to free and open software.33

Despite such concrete advances, the research team ran into significant difficulties during the FLOK project. As Research Director for the project, Michel Bauwens, has pointed out that, the main one was its relationship with the Ecuadorian government.34 Throughout the research phase, Bauwens notes, none of the ministers that supposedly supported the project was available for a single meeting with him. The Ministry of Knowledge prohibited its personnel from participating in the project until just before the Buen Conocer Summit. And the research team was not offered a seat at the table when the summit was planned, though it did enjoy complete freedom in conducting its research, outreach, and proposal development.

These problems may point to the government’s reluctance to fully support a process that it could not entirely control. The FLOK research team tried to involve many sectors of Ecuadorian society and conceived of the project as a co-creation from the bottom up. Correa’s administration may have been particularly reluctant to support such a truly participatory process after its long string of serious clashes with social movements. At the Buen Conocer Summit itself, political differences between the government and indigenous organizations (particularly the CONAIE) became obvious when they debated the definition of “ancestral knowledge”, their ideas diverging markedly.35

These lapses and shortcomings aside, one of the project’s great achievements is surely the uptake of “knowledge commons” ideas and paradigms elsewhere in the world. FLOK’s coordinators created a wiki — an open, public, worldwide forum— on further commons-oriented policy developments, and FLOK team members have given workshops around Europe based on their project’s findings and offered the Commons Transition Plan up for discussion. A book of policy proposals created by FLOK has been used in Colombia, Chile, Italy, and Spain and has formed the basis for more than half a dozen Commons Assemblies in France, as well as a European Commons Assembly.36

In Ecuador, an interesting twist took place well after the FLOK project formally ended. In 2013, Ecuador’s government engaged thousands of its citizens (and other contributors from around the world) in a “wiki legislation” process, eliciting comments on a proposed “Social Knowledge, Creativity and Innovation” bill whose content appears to have been inspired partly by the FLOK process.37 Over 1.7 million visitors viewed an initial draft of the bill and 16,000 registered users submitted over 40,000 comments, which influenced the final draft.

The final law, which entered into force in December of 2016, repealed and replaced Ecuador’s standing intellectual property legislation. It also featured a “general disposition against planned obsolescence,” the practice of designing consumer goods to rapidly become obsolete. Expressly to encourage local research and innovation and reduce technology imports, the law makes a host of products unpatentable and recognizes the collective rights to traditional knowledge. The new law also defines access to certain goods as human rights, allowing the state to authorize their use without the right-holder’s explicit permission, and requires all private companies that get state contracts to transfer technology as part of the bargain.

While reflecting many of the FLOK project goals, this bill appears to have been drafted without any direct coordination or collaboration with FLOK participants. The Director of the Ecuadorian Institute on Intellectual Property, Hernán Núñez, has said that the process leading to the final draft of the bill represents the first of its kind initiated by a government, rather than by civil society. While perhaps that is technically true, it fails to recognize the influence the firmly bottom-up FLOK process undoubtedly had on the initial draft of the bill.38

Even while Ecuador’s new Social Knowledge bill signals the institutionalization of the citizen-initiated FLOK process, the lack of coordination and collaboration with the very groups that gave birth to FLOK may be another example of government mistrust of social movements and civil society groups. If so, it represents reversion to traditional top-down governance principles. Again, the question is what further progress toward a more just, equitable and sustainable economy may have been achieved had the Correa government found ways to work together with social movements and civil society organizations to reach shared goals.

Conclusion

After Lenín Moreno was elected in April of 2017, political scientist Thea Riofrancos wrote that “after a decade of left rule, Ecuador is at once more equal and more unequal, more democratic and more centralized, radically transformed and mired in historic patters of domination that date to the colonial era.39 ” Such are the contradictions of the Correa years.

Yet, what many commentators consider the biggest of those contradictions in Ecuador’s “citizens’ revolution”—Correa’s criminalization of protest and general dismissal of social movements’ role in working toward a socialist economy—may actually have been the president’s chosen political strategy for consolidating social and economic gains, like the reduction in poverty and increased investment in health and education. For right or wrong, Correa represents one more in a long line of populist caudillos40 the continent is famous for. While breaking from neoliberalism the way that the Correa government did may have required the state to reassert its authority over the economy, the question remains: what might have happened had the administration worked effectively with social movements to forward its goals?

Correa’s successor, Lenín Moreno, who assumed office in May 2017, has promised to respect dissent and foment dialogue, but it is too early to tell if his government will pursue a different relationship with social movements than Correa’s administration did.

Given declining oil prices, the new president’s slim margin of victory, and Ecuador’s increased indebtedness to China, Moreno’s mandate is not as strong as it could be. So his success may very well rest on his ability to unify the left and bridge the divide that the País Alianza party created between itself and the major leftist social movements. With Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay’s turn to the right, Maduro’s tenuous hold in Venezuela, and the Evo Morales government’s neglect of Bolivian social movements, it may be up to Ecuador—out of all the pink tide countries—to show that social movements and the state can work together to bring about radical change.

- 1Clare Kendall, “A New Law of Nature”, The Guardian UK, (Sept. 24, 2008), http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/sep/24/equador.conservation; Paul Dosh and Nicole Kligerman “Correa vs. Social Movements: A Showdown in Ecuador”, NACLA Report on the Americas Vol. 42 Iss. 5 (2009)

- 2Marc Becker, “Indigenous Movements, and the Writing of a New Constitution in Ecuador,” Latin American Perspectives, Vol 38., No 1 (2011): 47-62

- 3Pablo Vivanco, “Is Ecuador’s Historic Left Working with the Right Against Correa?”, TeleSur, August 20, 2015, http://www.telesurtv.net/english/analysis/Is-Ecuadors-Left-Working-with-the-Right-Against-Correa-20150820-0027.html

- 4Federico Fuentes, “Ecuador: Correa Responds to ‘Leftist’ Critics,” Green Left Weekly, November 10, 2012, https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/ecuador-correa-responds-leftist-critics

- 5The Yasuní-ITT refers to Correa’s 2007 offer to suspend all drilling in the Yasuní National Park in response to demands from local indigenous groups. After deploying the military to stop the protests and arresting 45 of them under terrorism charges, Correa proposed to halt all drilling in exchange for $3.6 billion he implored the international community to contribute as climate justice reparations for the Global North’s historic extraction of Global South riches.

- 6”Marc Becker, “Indigenous Movements, and the Writing of a New Constitution in Ecuador,” Latin American Perspectives, Vol 38., No 1 (2011): 47-62

- 7Author’s translation of Article 48 of the Ley Orgánica de la Participación Ciudadana, “la Asamblea Ciudadana Plurinacional e Intercultural para el Buen Vivir como espacio de consulta y diálogo directo entre el Estado y la ciudadanía para llevar adelante el proceso de formulación, aprobación y seguimiento del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo.”

- 8Carlos de la Torre, “In the Name of the People: Democratization, Popular Organizations, and Populism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador,” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, No. 95 (October 2013), pp. 27-48

- 9“La Pobreza en Ecuador Descendió de 38% a 26% entre 2006 y 2014 Según Estudios del Banco Mundial y el INEC,” Andes, April 13, 2016, http://www.andes.info.ec/es/noticias/pobreza-ecuador-descendio-38-26-entre-2006-2014-segun-estudios-banco-mundial-inec.html

- 10Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston and Lara Merling, “Decade of Reform: Ecuador’s Macroeconomic Policies, Institutional Changes and Results,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2017 (last accessed June 8, 2017), http://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/ecuador-2017-02.pdf

- 11Banco Nacional de Ecuador, “Libro I. Política Monetaria-Creiticia. Título Decimocuarto: Reservas Mínimas de Liquidez” (2009), accessed 12/21/16, https://www.bce.fin.ec/documents/pdf/reserva_m_liquidez/codRegulacionRML.pdf

- 12Banco Nacional de Ecuador, “Instructivo de Reservas Mínimas de Liquidez (RML), y Coeficiente de Liquidez Doméstica (CLD)” (2013), accessed 12/21/16, https://www.bce.fin.ec/documents/pdf/reserva_m_liquidez/2013_instructivo_rml_y_cld.pdf

- 13Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston and Stephan Lefebvre, “Ecuador’s New Deal: Reforming and Regulation the Financial Sector,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (2013)

- 14Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston and Stephan Lefebvre, “Ecuador’s New Deal: Reforming and Regulation the Financial Sector,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (2013)

- 15Freddy Paúl Llerena Pinto, M. Cristhina Llenera Pinto, M. Andrea Llerena Pinto, Roberto Saá, “Social Spending, Taxes and Income Redistribution in Ecuador”, Commitment to Equity working paper, 2015

- 16Later renamed the National Corporation for Popular and Solidarity Finance (La Corporación Nacional de Finanzas Populares y Solidarias or CNFPS)

- 17Ecuador: Economía y Finanzas Populares y Solidarias para el Buen Vivir, Programa Nacional de Finanzas Populares, Emprendimiento y Economía Solidaria, 2012, http://www.finanzaspopulares.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/07/Ecuador-Economia-y-Finanzas-Populares-y-Solidarias.pdf

- 18Resultados de la Gestión 2008-Jun2014, La Corporación Nacional de Finanzas Populares y Solidarias, accessed 12/20/16, http://www.finanzaspopulares.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/08/Principales-resultados-de-la-Gesti%C3%B3n-2008-JUN-2014.pdf

- 19Sistematización Encuentro de Finanzas Populares (2014), accessed 12/21/16, http://economiassolidarias.unmsm.edu.pe/sites/default/files/Sistematizaci%C3%B3n%20Encuentro%20de%20Finanzas%20Populares%2025-11-2014.pdf

- 20Programa de Gobierno 2013-2017 “Gobernar Para Profundizar el Cambio: 35 Propuestas para el Socialismo de Buen Vivir” (2013), accessed December 2, 2016, https://carlosviterigualinga.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/programa-de-gobierno-2013-20171.pdf

- 21Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston and Lara Merling, “Decade of Reform: Ecuador’s Macroeconomic Policies, Institutional Changes and Results,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2017 (last accessed June 8, 2017), http://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/ecuador-2017-02.pdf

- 22Everett Rosenfeld, “Ecuador becomes the first country to roll out its own digital cash,” CNBC, February 9, 2015, http://www.cnbc.com/2015/02/06/ecuador-becomes-the-first-country-to-roll-out-its-own-digital-durrency.html

- 23“10 Things to Know About Ecuador’s Electronic Payment System,” Ecuadorian Embassy in the United States, last accessed June 8, 2017, http://www.ecuador.org/blog/?p=4184

- 24“JP Morgan Says Not to Worry as Ecuador Promotes Digital Currency,” Bloomberg, last accessed November 12, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-06-02/jpmorgan-says-not-to-worry-as-ecuador-promotes-digital-currency

- 25“Gobierno de Ecuador fortalecerá esquema de dinero electrónico con el apoyo de la banca privada,” Andes, May 31, 2017, https://www.andes.info.ec/es/noticias/gobierno-ecuador-fortalecera-esquema-dinero-electronico-apoyo-banca-privada.html

- 26Author’s translation of “un modelo democrático, incluyente y fundamentado en el conocimiento y las capacidades de las y los ecuatorianos”

- 27“How the FLOK Society Brings a Commons Approach to Ecuador”, Shareable, last accessed October 16, 2017, http://www.shareable.net/blog/how-the-flok-society-brings-a-commons-approach-to-ecuador%25E2%2580%2599s-economy

- 28“Commons Transition: Policy Proposals for an Open Knowledge Commons Society,” compiled and edited by Stacco Troncoso and Ann Marie Utratel, P2P Foundation, 2015, http://commonstransition.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Commons-Transition_-Policy-Proposals-for-a-P2P-Foundation.pdf

- 29“Best Practices for CBPP Communities and Policy Recommendations,” P2P Value, September 30, 2016, https://p2pvalue.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Deliverable_2.3-updated.pdf

- 30“Commons Transition Plan (FLOK Version),” https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Commons_Transition_Plan_(FLOK_version), last accessed June 8, 2017

- 31George Dafermos, “Building a Society of the Commons in Ecuador,” last accessed June 8, 2017, http://procomuns.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/dafermos-procomuns.pdf

- 32“Interview with Dafernos, a FLOK Researcher at Ecuador,” Commonsfest, March 19, 2014, https://commonsfest.info/en/2014/sinentefxi-me-ton-ellina-erevniti-sto-ekouador/

- 33Cheryl Martens, “Questioning Technology in South America: Ecuador’s FLOK Society Project and Andrew Feenberg’s Technical Politics,” Thesis Eleven, 138, Vol 1 (2017):13-25, DOI: 10.1177/0725513616689393

- 34“Michel Bauwens: FLOK Economics Failure in Ecuador—Lessons,” Public Intelligence Blog, July 19, 2014, http://phibetaiota.net/2014/08/michel-bauwens-flok-failure-in-ecuador-lessons/

- 35Cheryl Martens, “Questioning Technology in South America: Ecuador’s FLOK Society Project and Andrew Feenberg’s Technical Politics,” Thesis Eleven, 138, Vol. 1 (2017): 13-25, DOI: 10.1177/0725513616689393

- 36author’s personal communication with FLOK project Research Director, Michel Bawuens, December 16, 2016

- 37“Inside Views: A New Model for IP: Interview with Ecuador IP Office Director Hernán Nuñez Rocha,” Intellectual Property Watch, October 13, 2015, https://www.ip-watch.org/2015/10/13/a-new-model-for-ip-interview-with-ecuador-ip-office-director-hernan-nunez-rocha/

- 38“Código INGENIOS, un proyecto de ley pensado por y para el talento humano,” Andes, July 20, 2015, http://www.andes.info.ec/es/noticias/codigo-ingenios-proyecto-ley-pensado-talento-humano.html-0

- 39Thea Riofrancos, “Ecuador After Correa: Contradictions and dilemmas of left populism in Latin America,” N+1 Magazine, April 28, 2017, https://nplusonemag.com/online-only/online-only/ecuador-after-correa/

- 40a charismatic, often authoritarian leader, a political boss or overlord