A personal introduction

In the interest of full transparency, this essay is personal. When it comes to journalism, I’ve been on a career-long search for an effective, sustainable alternative to corporate mono-speak. In all that time, regular people have never had more communications capacity than we have right now. But the goal of a functional, public media sphere remains as distant, if not more distant than ever, and the power gap separating poor from wealthy media grows more dangerous by the day.

I first thought of myself as a journalist on the day I saw a policeman shoot and kill an unarmed man in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in my early twenties. I had no credentials, no contract, no formal relationship to any media outlet, but I knew I was witnessing something important—and I was familiar with a community radio station in New York City that broadcast stories from non-professionals like myself. Indeed, listener-supported, bottom-up reporting, mostly by volunteers, was the business-model of Pacifica station, WBAI. Hours later (from a payphone), I called them up and filed my report.

An early report from Laura Flanders, the author of this essay. (Her segment starts around the 3’ mark.)

Three decades on, a young woman in a war zone doesn’t need a radio station. She’s likely to have a high definition camera in her cellphone and the ability to record breaking news and distribute it, live, to people all around the world, via the internet. Powerful communications tools are no longer the private possession of a handful of mostly affluent white men and the corporations who like them. Rebellious music can go viral, rebellious citizens can throw off dictators, and hashtags can become movements. But that doesn’t mean we’re not in a crisis.

Concentrating power and corroding democracy

The same explosion of innovation that made it easier for independents to reach an audience destroyed the old gatekeepers and their gates. Into the new, networked world gushed a flood of content, some of which was revolutionary, but most of it was commercial—and lots of it toxic. In a few short decades, the world wide web that had promised diversity, democracy, and decentralization had actually concentrated power, accelerated abuse, and left journalism struggling for breath in a no-conscience contest for clicks and cash.

It should come as no surprise. The business of US journalism is subject to the same policy choices on which it (sometimes) reports. For example, deregulation. As federal limits on the number of TV, radio, and print outlets a single company can own have been dismantled, we went from several hundred owners of major media outlets in the US to just a couple of dozen in the last two decades of the 20th Century. By the 2000s, the media businesses that remained were larger, more embedded in the global economy, and more committed to squeezing higher profits from their operations (in keeping with the get-richer-quicker ethos which they used their airwaves to promote.) New owners, especially those who came into the networks in the 80s and 90s—Disney (ABC), Westinghouse (CBS), and General Electric (NBC)—demanded for the first time that even their news operations made money. Today, the idea that a major corporation would see television as a civic responsibility rather than just more revenue generating “content” seems almost unthinkable.

As a result of this shift, it’s often now said that news has become more like entertainment. It certainly has become less like news. The big three networks cut back on resourcing journalism to the point that most of the world, not to mention most US state capitols, were barely covered. At the same time, advertising proliferated to the point that those who tuned in for half an hour of nightly news saw at least ten minutes of ads. As TV audiences, and ad dollars started fleeing, costly, actually reported news stories were replaced by in-studio punditry, cheaper both financially and otherwise. Newspaper newsrooms, meanwhile, were already decimated before the 2008 recession—and went on to lose hundreds of thousands of jobs during it. Today fewer than half as many reporters and editors work in any sort of news media as worked there when I started out.

While newsrooms were contracting, the internet was exploding, especially as a site of commerce. If corporations could market directly to consumers, they didn’t need to attach their ads to newspaper articles or broadcast shows. With accelerating speed, advertising dollars flowed away from journalism, migrating not just online, but specifically into social media and search engines. Corporations could get closer to customers (and get more information about them) by placing their ads on pages served up by Google than on the website of The Guardian or Truthout.

In a world without regulation or oversight, executives at Google, Facebook, and Amazon have accrued unparalleled power astonishingly fast. As Jonathan Taplin, Director Emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab, reports, between 2004 and 2016, Google’s share of the search engine market went from 35 percent to 88 percent in the USA (and more elsewhere). Amazon’s net sales soared from $6.9 billion to $107 billion, accounting for 65 percent of all book sales.

Consumers feel that what they are enjoying is abundance, even if it isn’t. A few originally-reported news stories and features are recycled, usually with no kick-back to the originators, gobbling up clicks all over the web. Talk about an extractive industry: Taplin reckons that for most of the last decade revenues flooded at a rate of some $50 billion a year from the creators of media (reporters, writers, artists, film makers, musicians) to the owners of media platforms. (From the workers, you might say, to landlords.) While corporate media outlets have often been owned by extractive industries, the new media are themselves extractive, making their profits off human data and creativity, and giving the public nothing—or worse than nothing—back. (The new corporations’ business model involves charging “consumers” for access to their own content, photographs, blogposts, music, contacts.)

If Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg runs for president in 2020 he’ll preside over a production, promotion, and advertising empire that holds news companies in virtual peonage. Facebook alone, Taplin reports, sucked $1 billion out of print advertising budgets in 2016, the same year that surveys show the social media platform was the primary source of news for forty-four percent of Americans. News organizations are held hostage: Buzzfeed and Huffington Post report receiving close to half of their views through Facebook’s precious portal and even old-school giants like the New York Times have agreed to disadvantageous deals just to keep Facebook serving up Times content. It’s no wonder that propagandists seeking to affect the US presidential election, or make a buck off it, favored Facebook as their misinformation site-of-choice.

Coverage of the 2016 election was brought to voters by media corporations obsessed with likes and ratings. Donald Trump dominated all the networks receiving more than twice as much airtime as Hillary Clinton and ten times as much as Bernie Sanders because, like him or hate him, his antics served as consumer click-bait. Trump was telegenic because he was TV-generated. Over fourteen seasons as host of The Apprentice, he’d reached an average of 10 million viewers every week. Just as b-movie actor Ronald Reagan had ridden CBS’s “General Electric Theater” to the California Governor’s mansion and thence the presidency, so too, troubled real estate developer Trump rode The Apprentice to national prominence and the White House.

What Reagan was to the Cold War, Trump is to triumphalist capitalism: a dangerous narcissist backed by highly motivated individuals and groups who’ve used the media to build their ranks, vilify their enemies, and bully the weak.

This is what media democracy looks like

Absolute power over the means of making meaning is good for authoritarianism but as the framers of the US Constitution knew, it’s no way to run a democracy. That’s why they put post offices in the Constitution, and supported cut-rate postal rates for periodicals and pamphlets.

“The whole system [of democracy] doesn’t come alive without a functioning media” says media historian and Free Press co-founder, Robert McChesney.

The same holds true for any next system. We can’t build civil society without civic-minded journalism. We certainly can’t cultivate solidarity economics, foster inclusive governance, and create beloved community with cash-controlled media that gives us fake news and fake friends, and teaches us to hate, rate, and “fire” one another.

The same media corporations that have sold generations of Americans (and thanks to globalization, the world) on competition, consumerism, fossil fuel extraction, and war are underwritten by multinational corporations that stand to profit from all those things. Exceptional reporters and reports occasionally break through, but the media operations built by big business suffer from the same, top down, pro-white, pro-patriarchy, pro-profit biases as their corporate parents. Decision making, dollars, and celebrity is concentrated at the top. A few receive a lot; the majority, very little.

Independents can compete. The Young Turks and Democracy Now broadcast to millions of viewers and listeners daily. Each got a lift from a pre-existing media institution (Pacifica Radio launched Democracy Now; Cenk Uygur did a stint as a host on MSNBC), but their models show that given the chance, independent media makers can break through, even in a crowded, uphill race. But it’s not a fair contest if access to the track is controlled by multinational corporations who write the rules and pay the umpires and also field a team.

Relying on a handful of billionaires to save journalism is risky. For every Pierre Omidiyar (who funds the investigative site, The Intercept), there’s a member of the Mercer family bankrolling racist Breitbart News. The experience of Air America Radio (where I hosted a show from 2004-08), suggests that liberals don’t have the same long-term tolerance for losing money that right-wing media investors have (probably because they don’t see on the horizon such a directly positive impact on their self-interest or bottom line.)

Monopolies abhor choice, by definition. When in late June 2017, Amazon’s $13.7 billion deal to acquire the grocery chain Whole Foods was reported in Amazon’s already-acquired media outlet, The Washington Post, it was noted that the Seattle-based company had recently been granted a patent for technology that would block shoppers from comparing prices from their mobile devices while shopping. If their attitude to consumers’ choices reveals anything about their approach to other decision-making, we’d be mad to leave monopoly capitalists in charge of the media that powers our democracy.

How to get to the media system we want? To paraphrase McChesney, the path to that promise of diverse, decentralized, democratic media goes through diverse, decentralized, democratic media activism. Starting with journalism.

Well-placed stories can make a difference. After The Milwaukee Journal ran a four-part series on the legacy of disinvestment in the city’s Black communities that concluded with a stirring look at Cleveland’s Evergreen Cooperatives as a possible model for a remedy, several city council members proposed starting something similar in Milwaukee, reports author and Democracy Collaborative co-founder, Gar Alperovitz. “There are more and more friends out there, who are trying to use their power in existing media.”

What would our world look like if our media showed us as much collaboration as they do competition? If in lieu of the nightly Wall Street report (or at least alongside it), journalists brought us the up-to-the minute news of all sorts of bottom-up and worker-owned businesses that were operating in ways we’re currently told are impossible? Some media outlets, including Yes!, Next City, and my own show (formerly GRITtv), go out of their way to report on forward-looking innovation. On the Laura Flanders Show, we feature people developing models that are shifting power from the few to the many in the worlds of economics, arts, and politics. Every week, on TV, radio, and online—taking inspiration from Texan maverick Jim Hightower—we attempt to create a place where “the ones who say it can’t be done take a back seat to the ones who are doing it.”

Like Yes!, The Laura Flanders Show is also a long-time member of the Media Consortium, a network of independent and community media outlets dedicated to values-driven journalism. In 2017, the Media Consortium, with the LF Show, launched a collaboration with the New Economy Coalition (which comprises some 180 high-road businesses, advocates, and research organizations) to improve the media skills of coalition members and to encourage better reporting on the “new economy” sector. Funded in part by the Park Foundation, the New Economy Reporting Project offers media training and year-long fellowships for journalists.

Working with journalists to commission or pitch stories on the “next system” will bring more reporting on these emerging alternatives to more Americans. Showing up with new sources of advertising, underwriting support, or exclusive breaking news, could make an even bigger impact. Just as old economy businesses, like fossil fuels and big-box stores, supported media that promoted their world view, so too “next system” businesses need to support media that popularizes new ideas. If civic-minded businesses and social justice organizations moved their media money and their breaking stories to values-aligned media (instead of buying, say, one full page color ad for $200,000 in USA Today), we can imagine a world in which the combined advertising power of the country’s public banks and next-generation energy utilities, along with locally-rooted businesses, non-profits, co-ops and credit unions could undergird diverse media operations in every community in a virtuous cycle of mutual support indefinitely.

Why ownership matters

To shift the culture and impact policy in a systematic way, however, this next system media needs a new system of media ownership. A people-owned, public media system is possible. Other countries have one. You can see glimpses of it in the US in the media cooperatives and municipally-owned internet systems that are popping up across the country, and in the reporting collaborations that emerge whenever critical stories break that the corporate media ignore, like the uprising at Standing Rock, the movement for Black Lives, and before that, Occupy Wall Street.

Experiments of all kinds exist to pay for independent, non-profit journalism. Joe Amditis, of the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University told The LF Show about the Community Information District, a concept in development in New Jersey, that would levy a local tax or fee to meet information needs in the same way that special service districts fund public services like fire departments or sanitation. “Communities could choose what to do with the money,” says Amditis. “They might decide to hire a reporter for a year to conduct a specific piece of research.” Amditis appeared on the program alongside Dru Oja Jay, co-founder of Canada’s longest-lived media co-operative, The Media Co-Op, itself an interesting experiment in democratizing media ownership.

Cooperative media institutions share power between reporters, editors, and consumers, shrinking or even eliminating the influence of advertisers. The Associated Press was formed in 1846 by five daily newspapers in New York City to share the cost of covering the Mexican American War. The Cooperative Newspaper Society (which also published magazines and books) advanced alongside, and as a critical part of, the cooperative movement in Great Britain at the turn of the last century. Today’s successful media co-ops include Germany’s Tageszeitung, a progressive daily newspaper founded in 1979 and re-organized as a coop in the mid-1990s, and La Diaries, a left-oriented Uruguayan cooperative newspaper that has become the second-most widely read paper in that country in just over a decade.

Such bottom up innovation is vital, but the creation of a truly public media system ultimately also requires public policy and the power of the state.

“Journalism’s essential nature as a public good was masked for 100 years by advertising, but ads never covered more than half the operating budget of newspapers,” says McChesney. “If journalism’s a public good, it needs public support like other public goods, like parks and fire departments.”

Public broadcasting in the US is supported in principal through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a private, non-profit corporation funded by the federal government. It’s a process that’s become increasingly politicized and decreasingly functional since its founding in the 1960s, such that PBS today has been drained of nearly all juice and innovation, in many cases with the same anchors hosting the same shows for a generation.

Public broadcasting in other countries is paid for through a dedicated tax on advertisers or charge to consumers, or as in the UK, a TV “license” charged to any household wishing to watch or record TV. (British TV viewers are required to pay 147 Pounds or roughly $160 annual fee, or face prosecution). The challenge is to have government funded media, without government intervention in what gets reported. (While many Americans appreciate the BBC as a reliable source of noncommercial world news, people living under British rule, in Northern Ireland for example, can point to myriad examples of censorship and pro-government bias.) To address that challenge, economist Dean Baker has proposed a check-off on the federal income tax form that would give each tax payer a set amount to donate to the non-profit media institution of their choice.

Government has played a role in communications before. (It’s part of the true story of US capitalism that decades of libertarian opinion-shaping has done its best to bury.) The 1912 Radio Act established that radio stations had to be licensed by the government. The 1934 Communications Act gave the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) power to ensure that the privilege of holding a license to broadcast on the public’s airwaves came with a responsibility to serve the public interest. Civil rights attorney, Clifford Durr (an FDR appointee to the FCC) sought to require broadcasters to abide by certain basic rules, among those, that they’d promote live, local shows; devote programming to discussing public issues; sustain “unsponsorable” programs; and eliminate “excess advertising”. The Commission required broadcasters to put certain programming information (including but not only information on any paid political programming) in a “public inspection file” “so that the public will be encouraged to play a more active part in dialogue with broadcast licensees.” (Those files are still supposed to be public.)

The FCC of that time forced NBC to sell one of its two networks, leading the formation of the American Broadcasting Company in 1943. The 1949 “Fairness Doctrine” stayed in place for forty years. It didn’t dictate programming but it did require “balance” over the broadcast schedule. The 1970 Prime Time Access Rule, required TV stations to air at least two hours of locally-produced programming in prime time, between 6-8 pm weeknights (rather than nationally-syndicated shows). It’s the single reason that local news survives at all, and with it local reporters across the nation. Government put pressure on manufacturers too, in the 1950s, insisting that radio receivers served both AM and FM bands, and later, that TV sets received VHF as well as UHF signals.

None of this happened without public pressure. In the 1920s, educators, church groups, labor unions and the left pushed for public, non-commercial space on the radio dial. Thousands of non-commercial, community, campus, and reservation-based AM and FM stations continue to exist, connected by independent organizations like National Public Radio, Public Radio International, and Pacifica, as well as the National Federation of Community Broadcasters (NFCB). The public libraries of the media world, an estimated 500 - 800 community radio stations exist on miniscule budgets across the USA. Some 235 stations belong to the Pacifica Affiliates Network. On Native American reservations, Black college campuses, and in heartland cities as well as rural “red” states, they share programming through Pacifica’s AudioPort, which receives requests for assistance from about three new production groups every week, says its director, Ursula Ruedenberg of KHOI in Ames, Iowa.

“The people who build and run these stations, are short on resources but long on innovation and democratic idealism,” says Ruedenberg. AudioPort, the network’s content sharing platform, hasn’t crashed in over a decade.

“The network is more than a plan or a good new idea; it is an American tradition that is highly functional and dynamically facilitating daily cooperation and collaboration,” says Ruedenberg.

Low-power FM stations got a boost in the last decade after the passage of the Local Community Radio Act in 2010 which loosened the licensing laws for nonprofits. With massive organizing by groups like the Prometheus Project, the number of low power stations doubled between 2014 and 2016. Over half the attendees at the 2017 Grassroots Radio Conference in Albany, NY represented low power FM stations that did not exist three years ago.

Making media, making community

As broadcasting (over the airwaves) began to give way to cable (through fiber-optic lines), media activists forced corporations to give something back through franchise agreements. In exchange for monopoly access to the consumers in a given area and access to public land, media activists in the 1960s and 70s pushed local governments to levy a tax on cable operators that was to be tagged directly to on-going support of public media, meaning infrastructure (stations, equipment, staff), a place on the cable system, and an ongoing stream of general operating funds. When satellite television started a decade later, people pushed for non-profit, public-interest channels in that medium too.

Over three thousand Public, Educational and Governmental (PEG) access organizations and community media centers exist in the US. Depending on the agreement with the city (and the size of the revenue base) cable taxes fund fully equipped channels, as well as free or low cost classes and programming slots for residents to use for educational and non-profit purposes on a first-come, first-served basis. Public Access or PEG stations emphasize local programming, but play some national programming too, through non-profit distributors, including DeepDish TV and the Boulder-based FreeSpeech TV. (LinkTV and FSTV have their own dedicated channels on satellite, and other services, like ROKU too.)

Deep Dish TV’s early satellite broadcasts included coverage of the organizing demanding solutions to the AIDS epidemic.

Unfortunately, access doesn’t come with promotion. TV guides don’t list public access shows and other media rarely review public access shows. When they do, it’s often belittling or disparaging. That’s hardly surprising (given who owns other media). It’s also true that the open-access “free speech” rule is open to abuse. Still, “public access makes television a community forum,” writes DeeDee Halleck one of those media makers who fought for it, in her movement memoir, Handheld Visions. “Even if it’s not watched much in normal times, it’s there in case of emergency.”

In an era in which most media is not local and of limited relevance to local communities, public access stations like Manhattan Neighborhood Network or Brooklyn Community Access Television or Philadelphia Community Access Media (PhillyCAM) are creating media that is locally-determined and publically accountable, says Mike Wassenaar, President and CEO of the Alliance for Community Media, which serves the “PEG” stations.

In Brooklyn, responding to changing times has meant launching a professionally produced and curated channel with a focus on the arts and culture. MNN recently launched NYXT.NYC, a channel playing 2-3 minute video shorts made by scores of local community organizations.

“The future of MNN is inextricably tied to the future of our community” says MNN’s Director, Dan Coughlin. MNN’s also struck an agreement with FreeSpeech TV to dedicate one channel to its content (including Democracy Now and The Laura Flanders Show.)

In Philadelphia, the people at Philadelphia Community Access Media have launched a 24/7 low-power FM radio station alongside their TV channels, and teamed up with the public library system to host events and trainings.

“Making media can be a tool for community healing,” says Antoine Haywood, Membership and Outreach Director at “PhillyCAM.” Not only the finished product but also the process gives people a way to air contrasting views on controversial issues like gentrification and policing, while working together.

Social media could help public access stations get the coverage or attention (or healthy criticism) they deserve. But it better happen fast. Since 2005, policy changes have restructured how many franchise agreements are forged, giving less power to cities and more power to states. PEG stations have been particularly hard hit in the South. Between 2010 and 2016, People TV in Atlanta lost as much as 70 percent of its funding each year, says Haywood, who worked there before coming to Philadelphia.

Seizing the means of distribution

Offering both cable and increasingly, broadband access, many cable companies are re-branding themselves as internet service providers or “ISPs.” Under the Obama administration, the FCC classified broadband as a “public good” comparable to a public utility, like water or telephone service. That’s a classification Donald Trump’s FCC chair Ajit Pai wants to reverse.

“If we don’t extend the system of cable compensation from cable to broadband, we’ll have no way to derive revenue,” says Wassenaar.

Some towns, like Eugene, Oregon have taken the initiative of extending a “telecom tax” to all broadband providers through local legislation. Others have opted to municipalize broadband, arguing that internet access is critical for local development as well as youth retention. Affluent spots like Santa Monica have done it—as have nine communities in Tennessee, among others. Providing not-for-profit, community-owned broadband service, the biggest, Chattanooga, has won the love of its users by keeping costs low and bandwidth high. It’s also pushed them into a hard-fought fight with the Big Cable (now Broadband) lobby, and their allies on the reactionary American Legislative Exchange Council. Where local legislators can’t be persuaded to ban municipalization pre-emptively, they’re being pushed to pass laws that bar cities that have publically owned service from extending that service beyond city limits.

None of that is stopping activists like those with the Rural Broadband Campaign. While contesting state and local bans through lawsuits and working with legislators, they’re simultaneously investigating other ways to meet their communities’ needs. William Isom II of the Rural Broadband Campaign, believes that Big Cable’s denial of service could be turned into an opportunity to build local media power in much the same way rural co-ops grew up to bring electricity to underserved parts of South (especially the African American South under Jim Crow). In fact, Isom and his colleagues believe rural electricity co-ops might themselves be good partners. Tennessee’s Broadband Accessibility Act allows existing electrical co-ops to provide broadband.

“While they’re not always very democratically run, electricity co-ops have the potential to be democratic written in to their structure,” says Isom.

Samir Hazboun at the famed civil rights school, the Highlander Center, believes that new, locally-owned communications co-ops could be a way to earn revenue, pay local workers, and generate money for local production hubs. Highlander sits atop a mountain that could house a repeater antenna capable of receiving service from Nashville and shooting it down into the valleys and hollers below. The technology’s not as complicated as the companies would have people believe, says Hazboun.

“Paying wholesale for the bandwidth, with low overhead, we’d cut costs, and all along the way be putting power in local hands and demystifying both the product and the process.”

That’s the same approach the Detroit Community Technology Project hit on after surveys revealed that 60% of households in that city didn’t have access to broadband. “Forty percent (including 70 percent of schoolchildren) had no internet connection at home or via mobile,” says Diana Nucera. Nucera’s household relied on dial-up service. The Detroit Digital Justice Coalition used a grant from the Obama Administration to launch what they call their Digital Stewards Program.

Essentially, the program builds meshed wireless networks across Detroit’s least-well served areas using wireless sharing technology. Line-of-sight connectors send signal, router to router, from rooftop to rooftop.

“We share a cup of sugar, why not share a few megabytes of bandwidth?” says project director, Nucera.

Users of the meshed network can access the worldwide web and also each other through an off-the-web “intra-net” which permits people to talk with each other about day-to-day things, but also to monitor local pollution levels and ICE (immigration enforcement) raids.

“While spreading ownership, we’re building trust and resilience,” Nucera says.

“At the end of the day it’s a matter of whether local communities have a say in their future,” says Wassenaar. “Community media have an essential role to play in that. It’s the way people understand themselves and their role in society.”

As the telecom industry looks to the next generation of wireless technology, possibly 5G (which will be needed, for example, for self-driving cars) corporations may again need access to public land for new infrastructure (or to update existing cell towers). That gives communities another chance to demand something in return.

In the last decade, media activists (and on-air personalities) have roused millions of Americans to write comments to the FCC in defense of the “neutral”, one-size-fits all internet. So far, each time, they’ve won. But beyond opposing threats, are the public’s “asks” big enough?

Demanding the impossible

“We seem to have gotten out of the habit of making big demands” said Columbia professor Tim Wu, who coined the term “net neutrality”, on a FreeSpeechTV/Manhattan Neighborhood Network special I hosted this July.

Reporters and publishers have a long record of accomplishing the seemingly impossible dating back to the nation’s earliest days. As Juan Gonzalez and Joseph Torres report in their award-winning history, News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race in American Media, “Few Americans realize that people of color published more than one hundred newspapers in this country before the Civil War. This new press, unlike the white-owned commercial publications of that era, or the foreign-language newspapers of the early European immigrants, or even the early radical labor newspapers, was forged in direct opposition to racism and colonial conquest. From the beginning, it spoke to its readers in Spanish and Cherokee as well as English, and later in Shawnee, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean.”

The Laura Flanders Show recently secured a small grant to study social justice movement media assets. For that study, released in conjunction with this paper, producer, reporter Jordan Flaherty spoke to people at over thirty organizations. Addressing racism, he concluded, has to be central to any next media system. You can read the full report here. White male dominance isn’t only morally wrong, it makes for less good journalism. Journalists from frontline communities have a front-row seat to what’s happening as it relates to everything from war to policing, to climate change. Yet, even in progressive media, most large institutions are still run by white people (mostly men), in big cities. They tend to determine the agenda first, and report second. But historically, that’s not how America has advanced. Rather, to the contrary, trailblazing journalists have challenged the country and changed the agenda from below.

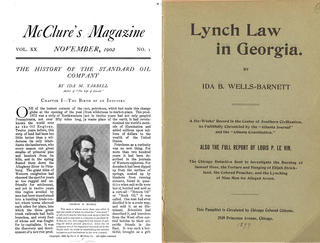

Investigative reporter Ida Tarbell took on Standard Oil and the most powerful CEO of her time before women could even vote. Ida B. Wells covered the rape and lynching of her fellow African Americans even as the Ku Klux Klan was out for her life. Pacifist, Lewis (“Lew”) Hill, founded KPFA, the first listener-supported radio station, and the Pacifica network, in the patriotic, red-baiting days immediately following WWII.

Risk-taking, moral courage, cooperation, multiple income streams, diverse stakeholders, mutual aid: independent media makers have come up with many of the innovations that are driving the “new economy”. We share many of the same principles, and many of the same challenges, too.

Hill invented the listener-pledge drive a decade before National Public Radio and years before anyone came up with the term “crowdsourcing”. Bay Area talk show host, “Davey D” ran an e-marketing business to fund his “Hard Knock” radio program and crowd-sourced from his church to go to Ferguson after the killing of Michael Brown. Emmy-Award winning documentary film maker, Jon Alpert, a former New York City cab driver, and his wife Keiko Tsuno started showing their documentaries in the early 1970s from a converted mail truck on their street. “Public feedback made us better” says Alpert.

“Elitism’s bad for news.” Over 44 years, their project DCTV has taught 75,000 students, mostly low-income young people of color, while producing two Academy Award Nominated films and award-winning works for PBS and the networks. “We’ve been making it up as we go along,” says Alpert. As for financial solvency: “the water line’s always somewhere between our upper lip and our nose.”

Appalshop, the globally acclaimed media center in Eastern Kentucky, received seed funding from a federal War on Poverty grant initially intended to equip locals with skills they could use to find work out of the area. Instead, Appalshop inspired generations of students not to leave, but rather to stay.

<

Appalshop’s 1971 film “Whitesburg Epic” provides a powerful example of the possibilities for community-embedded media.

Today it’s popular in philanthropy circles to celebrate profit/non-profit partnerships. The non-profit news operation ProPublica, partners with commercial media outlets to subsidize the cost of production and promotion of key stories. With additional time and resources, ProPublica collaborations have enabled many established media outlets to conduct important investigations with the established players giving them the PR push to have real impact. But they’re hardly the first media experiment in collaboration.

Pooling cameras, facilities and know-how, independent makers, stations, distributors, and their public covered opposition to the first Gulf War, the Seattle uprising, Occupy Wall Street, and the Movement for Black Lives long before the corporate media. For ten days in 2000, working with local and national volunteers, Amy Goodman and I were part of a 1200 strong collaboration which produced two live shows, as well as a round-the-clock radio feed and a daily newspaper for each day of the Republican and Democratic conventions. In 2011, I participated in another independent radio, TV, and print collaboration that covered the workers’ rights uprising in Madison, Wisconsin. In each case, local and national reporters partnered with local and national outlets at bargain basement cost thanks to the trust and relationships (forged largely in the Media Consortium) and the contributed support from viewers and listeners.

When for-profit media compete with non-profit media for donations and philanthropic support, they’re stressing public media’s already most-stressed out parts. Today everyone from The Atlantic to The New York Times are pleading for consumer contributions, and enticing memberships with online extras and perks. Journalists, rich and poor, it seems, are all crowdsourcing from what often feels like the same crowd, and rural-, low-income-, women-, and people of color-led media organizations fare worst.

Whose media revolution?

Americans have experienced revolutionary moments before; moments in which entire systems of governance, of production, of labor relations, and social organization, broke apart and stitched themselves back up in new ways. In every one of those moments, whether it was the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the Gilded Age, or the Silicon Valley age, media fueled the transformation and were transformed by it.

In our era of extreme capital accumulation, media capital has accumulated—extremely. What we need is a bottom-up remaking of our system, and new commitment to media as a public good.

NBC recently reported that the Amazon corporation is in the process of buying up television channels. The corporation, which already accounts for about a quarter of all online sales in the United States, is holding talks to “supersize” its video-channel business, not just in the US but around the world. That, even as the right-leaning Sinclair Broadcast Group, one of the largest owners of TV stations in the US is in the process of creating an ideologically-driven broadcasting behemoth that would reach some 72 percent of the television-viewing audience coast-to-coast.

Online, dozens of radical and progressive media outlets are reporting that Google and Facebook’s new search engine algorithms appear to be blocking their sites in the name of combatting “fake” news. Just one such site, AlterNet, reported this September that its search traffic plummeted by 40 percent—a loss of an average of 1.2 million people every month since the new algorithms went into effect. “The reality we face is that two companies, Google and Facebook—which are not media companies, which do not have editors, or fact checkers, which do no investigative reporting—are deciding what people should read, based on a failure to understand how media and journalism function,” said Alternet’s Don Hazen.

Institutions matter. Professional, not-for-profit, public journalism has passion; it even has some specks of infrastructure, but a grand pyramid of public interest reporting, news, culture and analysis, rests on a very few, very rusty, pillars of public media infrastructure. The public needs to recommit to the principle of journalism as a public good. The state needs to act as it did in times gone by. Public media needs financing, especially financing that will support the least well-endowed. Leveling the unequal media playing field isn’t only a matter of fairness: it’s critical for high quality journalism, the sort on which our democracy depends. And this kind of journalism is imperative if we are to bring into being the sort of “next system” we need.

In another age of extreme inequality, Ida Tarbell took on her era’s Amazon. The first investigative reporter in the modern sense, Tarbell’s research and interviews revealed how John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil had accrued its immense power. The price-rigging, corrupt practices, and abuses that Tarbell exposed helped to build the base of support for 19th century opposition to the monopolies of their day.

Said President Theodore Roosevelt about breaking up Rockefeller’s Standard Oil company and JP Morgan’s Northern Securities Trust:

The great corporations which we have grown to speak of rather loosely as trusts are the creatures of the State, and the State not only has the right to control them, but it is duty bound to control them wherever the need of such control is shown.

The way out lies, not in attempting to prevent such combinations, but in completely controlling them in the interest of the public welfare.

Corporate expenditures for political purposes… have supplied one of the principal sources of corruption in our political affairs.

We have plenty of investigative reporters like Tarbell. Their reporting could make a strong case for antitrust suits aimed at our authoritarian-leaning, too-big-for-democracy media. Just one of those suits, against Amazon or Google, along the lines of the Big Tobacco cases of a generation ago, could generate enough, in fines and reparations, to invest in “next system” public media. But journalism doesn’t change policy without politicians who feel heat from voters, and that sort of heat’s been cooled almost to freezing point by half a century of concerted effort by private interests who’ve invested in media to shift public opinion away from such matters. For half a century, starting long before it was financially profitable, those interests funded publishing, radio, TV, and internet personalities who advanced a libertarian, leave-it-to-the-market ideology once considered nonsensical and irrelevant.

That’s why media can’t be an afterthought for anyone seeking a “next system.” Without free journalism, there’s not only no free democracy, there’s no free-flow of ideas about things like capitalism, colonialism, border control, policing, climate change, or terrorism. Publicly-owned, not-for profit, diverse, civic-minded media is both the answer to the question and the way of raising the question about what ails us. While this has long been true, what’s different about this moment is that the ad-hoc communications systems we’ve cobbled together over the past 200 years to inform us and our choices, have spectacularly failed as our early warning system; failing to warn us of financial collapse, the rise of white militants, ecological disaster, and the likely blowback effects of our wars abroad. To the contrary, our money-driven media systems have tended to feed and accelerate those crises. The entire for-profit, for-the-few media system has failed so many, so badly, for so long that close to 100% of us, across all classes, races, gender identities, and countries of origin have an interest in a new civic journalism. The crisis facing journalism needs solving, not to save journalists but for the sake of civil society. Which means if ever there was a time to build broad support for redefining journalism as a public good, this is that moment.

The models we need

Drew Sullivan heads up OCCRP, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project based in Sarajevo. OCCRP connects investigative reporters and their organizations across the world, and provides resources that exceed their individual capacities. If the media outlets involved received even a small percentage of the money governments recover in fines and unpaid taxes based on investigative reporting, organizations like OCCRP would be well endowed. Sullivan estimates that the Project’s work has resulted in US $5.735 billion in assets frozen or seized by governments since 2009.

Marina Gorbis, of the Institute for the Future research group, convened media players this winter to reflect on the 2016 election and what became very clear, was that the media crisis we’re facing is part of a far bigger one. We can’t solve the media problem, without addressing the inequality problem, believes Gorbis, “We have such levels of inequality that it’s impossible to have a functioning democracy.”

Gorbis has proposed that “next system” thinkers consider Universal Basic Assets (as a corollary or substitute for Universal Basic Incomes.) Instead of marginally moving bottom dollar incomes, provide access as a human right to certain critical resources: some owned privately, some by governments, and others openly, by a defined group, like a Wikipedia or a Digital Commons. Communications commons could fall into that last category.

A journalism “commons” would provide an online home for verified data and reporting that could be accessed and contributed-to, by the public and social justice groups as well by journalists. That commons could be fed, and in turn feed, local reporters and their organizations on terms that might include returning revenues to the writer/reporter/originator for movie contracts, book deals, taxes and fees recovered, etc.

“Frankly, so much information-gathering with so much keeping the-results-to-ourselves is an inefficiency we can’t afford,” says Sullivan.

Republik’s powerful crowdfunding appeal

This spring, three years after one of Switzerland’s leading far right ideologues bought a one third share in the largest subscription newspaper in Basel, a journalism start-up called Republik, raised more than $2 million in two weeks (along with $3.5 million in investor capital) to do long-form journalism. More than 10,400 subscribers signed up, automatically becoming members of the Project R Cooperative which will own up to 49 percent of Republik (a for-profit publication). As reported by the Columbia Journalism Review, the investors will control about 20 percent, with the rest of the shareholders being founders and staff. Readers, investors, and staff all have some say while none has control. For transparency’s sake, they’ve created an open source platform for their contributing journalists, but Republik’s reporting will exist behind a paywall. The two models for the project early on, Republik co-founder Christof Moser told CJR, were Thomas Jefferson and Ida Tarbell.

For good and for bad, the old model of journalism is done for. Along with our democracy, it’s on life support. Any new economy worth fighting for needs a new media economy at its heart. We can tweak what we have, but tweaks won’t fix the problem. Public interest journalism needs a new system, a new life.