The monetary policy known as “quantitative easing” has been grabbing headlines recently. For months it has been at the center of Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein’s platform, where it’s cited as a way to “cancel student debt” and “bail out” a debt-shackled generation of former students who are suffering due to the excesses of Wall Street. To many, however, the idea of “cancelling student debt” always sounded a bit too good to be true, and now Stein and the Greens are on the defensive as pundits such as Last Week Tonight host John Oliver criticize the plan for being unrealistic, and even undesirable. But is it?

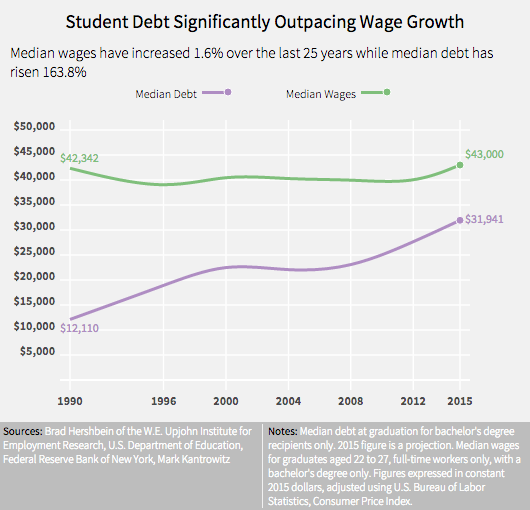

As student debt rises faster than wages, the risks of mass defaults increase—a student loan bubble.

What is Quantitative Easing?

Essentially, quantitative easing is a modern term for when a central bank creates money, and then introduces it into the money supply. Typically, this is done with the intent of stimulating a national economy during a period of economic crisis (see this BBC article for a slightly more in-depth explanation). While not exactly the “magic trick” Stein infamously claimed it to be, many still find the concept of quantitative easing difficult to grasp—likely because it seems to defy many of the oft-touted “rules” of free market economics. In reality, quantitative easing has been used many times without triggering economic collapse. In recent years the equivalent of around $12.3 trillion has been pumped into the global financial system worldwide via quantitative easing, and the United States government alone—through its own central bank, the Federal Reserve—created roughly $3.7 trillion of new money between December 2008 and 2014.

What About Inflation?

Perhaps the most common charge leveled against quantitative easing is that it must cause inflation. Leaving aside the discussion of “how much inflation is bad inflation,” it is important to point out that the potential for a certain amount of inflation-free quantitative easing already exists in the United States. Based on data provided by the Federal Reserve, the country’s current potential GDP is $17.02 trillion, while its actual GDP is $16.58 trillion. This leaves a cool $440 billion or so that could, through quantitative easing, be put towards buying up and paying off student loan debt. Assuming that a similar amount is available next year and the year after, all currently held student debt (amounting to around $1 trillion), could be entirely paid off within three years.

“Politically Difficult”

In a response to the Last Week Tonight segment, the Stein campaign stated that cancelling student debt via the Federal Reserve would be “technically possible, even if politically difficult.” While they didn’t cite the $440 billion figure above, the statement is still valid: the real issue is not whether the U.S. government could “cancel” student debt through quantitative easing, but rather what it would take for that to happen.

First, there is the issue of harnessing the political will to use quantitative easing for student loan debt. While politicians like Stein might be in favor of such a plan, the idea is still far from mainstream, and certainly has not been promoted by the leading presidential candidates or most state and federal legislators. Still, the potential for widespread support seems good, given that there are around 43 million student loan borrowers, whose debt also likely affects friends and family.

However, it is in considering the details of what such a plan might require that the true political hurdles are exposed, since giving elected politicians the ability to implement quantitative easing would likely require new laws to be passed. John Oliver alludes to this fear in his segment, saying:

The president does not have that authority. Only the Federal Reserve does and it does not take marching orders from the White House, because that would be extremely dangerous.

He goes on to warn against concentrating power in this way, suggesting that politicians would use it for personal gain and to fund pet projects which—while probably not a completely unfounded fear—obfuscates its more obvious potential: economic planning. Because if monetary policies such as quantitative easing can be used to “cancel” student debt, what else could they be put towards? Reparations for slavery? Single-payer healthcare? Free higher education?

Reclaiming the Power of the Fed

Likely every American could think of at least a dozen worthy causes to put $440 billion of quantitative easing towards every year. And while it does, by itself, have the potential to help reduce inequality in the U.S. (and even begin to tackle issues like climate change), it is, of course, a relatively small amount. Still, by opening the door to economic planning it could inspire more significant changes to our political-economic system.

For example, if the majority of Americans decide that they really like the form of redistribution demonstrated by a quantitative easing program, they might also support expanding economic planning more generally. How to pay for that? Well, there is already support for increasing taxes on corporations and the rich, which also happens to help reduce economic inequality. And thus the pathway towards a Sanders-style twenty-first century version of socialism becomes clearer.

At very least, the potential of quantitative easing and increasing our control over the Federal Reserve is worthy of further investigation, particularly by the nation’s younger generations, who are faced not only with endless student loan payments, but also with the task of tackling massive social and economic inequality and preventing environmental catastrophe.