Now that the deal for Amazon’s second headquarters has been struck, it’s worth asking if this is a package that its recipients should never have ordered.

Amazon announced that its “HQ2” will be split between two locations, Long Island City in Queens, New York, and Crystal City in Northern Virginia. Amazon says it intends to employ more than 25,000 workers in each site. But that does not mean that Amazon will be employing many residents from either the Washington, DC, metropolitan area or the boroughs of New York City. Rather, it will be attracting people from elsewhere to work on its new campus for more than $150,000 a year. Indeed, this is Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’s stated reason for siting the headquarters in two of the US’s richest and most rapidly gentrifying cities, according to its news release: “These two locations will allow us to attract world-class talent that will help us to continue inventing for customers for years to come.”

In exchange for a subsidy of over $1.5 billion, New York has been promised a donation of land for a single new school, a “tech startup incubator” and “new green spaces.” In exchange for a subsidy of almost $800 million, Arlington, Virginia, of which Crystal City is a part, will apparently not receive anything.

What the politicians who negotiated these deals will receive is a richer population. Not for their current population to become more financially stable, more secure or more fulfilled – but for a new population, which will push out many of the previous residents. They will govern a richer community, and the old community will be forced to move somewhere else.

The much-touted investment from Amazon is not in the existing communities in Arlington and Queens. It is in the communities to come — wealthier, less demanding of services like health care and housing. The people pushed out by rising housing costs in communities that already face affordable housing shortages will become another community’s problem, as will rising costs of living, shortages of living-wage jobs and the over-policing demanded by gentrifier populations.

It is unlikely that the hiring practices for these new positions will reflect the demographics of the metro areas they are being placed in. Just 5 percent of Amazon technical workers and managers in 2014 were African American, according to data Amazon filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, while 87 percent were either White or Asian. (The Washington metropolitan area is 54 percent people of color, and New York City is 55 percent people of color.) Already, residents of African American and Latinx communities in Washington and New York City have seen the history, culture, and institutions they built eviscerated by waves of gentrification. After having struggled with disinvestment and malinvestment by the financial sector, they now discover that their newly desirable communities — with easy access to public transportation and urban amenities — no longer have room for them.

The residents who will find jobs supporting Amazon’s presence — either with the contractors that will provide services like janitorial, at the shops where Amazon workers will buy lunch or grab groceries, or as a gig-economy driver — will be among those stuck with the leftovers: aging outlying suburban communities where they will struggle with long commutes and a worse quality of life.

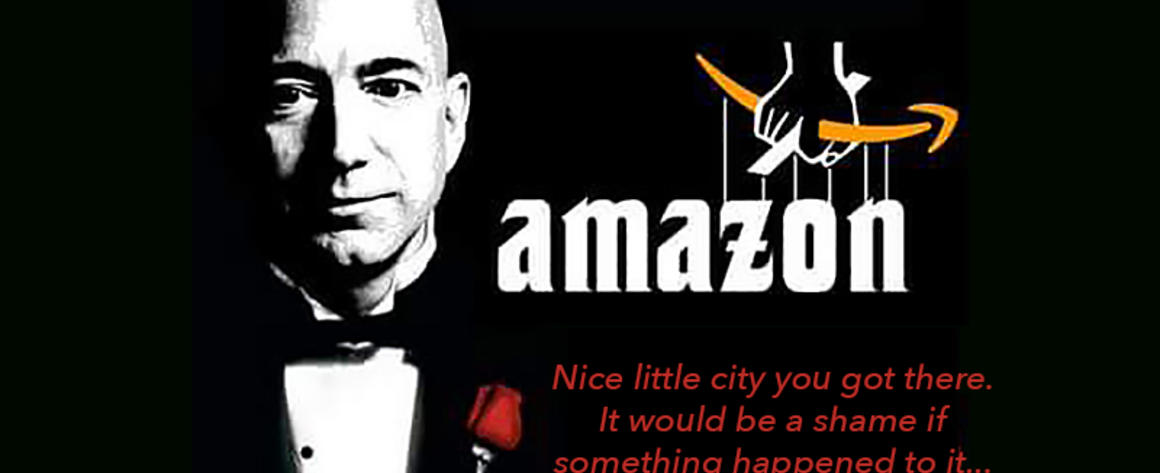

Billions of public dollars are being spent on this wasteful project to court one of the world’s biggest corporations owned by the world’s wealthiest man, a person who personally purchased The Washington Post five years ago pretty much with his pocket change. That money could have been spent by the cities who bid for Amazon’s HQ2 on building new affordable housing or rehabilitating existing housing projects, helping to seed community land trusts, improving schools, fixing ailing transit systems, green infrastructure and energy conservation projects and a host of other needs. All of these would have produced living-wage jobs more efficiently than handing financial incentives to Amazon, and would have done so without destroying the fabric of already struggling communities.

That’s why leaders from the tenants’ association at the US’s largest public housing project, as well as newly elected New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez came out against HQ2. The Amazon deal is a gentrification bomb. The cities that did not win this so-called prize are the ones better positioned to become winners.

This article was originally published in Truthout and is republished with permission.