Introduction

The information technology sector broadly defined is now at the leading edge of the capitalist system. Material production and distribution, enterprise and professional management, finance, insurance and real estate are all increasingly dependent on digital technology. In the second quarter of 2019 the top five firms in the world by market capitalisation were Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook. Their combined value of $4.7 trillion tracks the extent to which the broader economy of production and exchange currently relies on a relative handful of digital intermediaries.

Any attempt to reassert the primacy of democracy over private power must reckon with these leading firms and with the sector more generally. In what follows I set out the outlines of a socialist agenda for digital technology - a programme that begins with networked communications and shows how a ‘public option’ here opens up new possibilities for much more extensive popular oversight and direction of our economic, social and ecological systems. Technology will not save us from the overlapping and intensifying crises facing us. But it has an important contribution to make in a broader process of reform.

As well as this outline agenda, I set out some of the key structural features of the institution that will take primary responsibility for developing digital resources with which to articulate and inform a revived democracy. This institution, the British Digital Cooperative (BDC), will act as a space for egalitarian collaboration as well as rapid technical innovation. As such it is intended to bring some fragments of a better future into being in the here and now, where they are needed most.1

This report has been copublished with Common Wealth.

The Digital Sector under Capitalism

It is not OK for every move, emotion, utterance, and desire to be catalogued, manipulated, and then used to surreptitiously herd us through the future tense for the sake of someone else’s profit.

—Shoshana Zuboff

Welcome to the Hotel Northern California

The preeminence of the technology sector is particularly obtrusive in what Paul Sweezy and Paul A. Baran called ‘the sales effort,’ the realisation of profits through market research and advertising.2 The internet is now by far the most important medium for commercial manipulation in the world.3 More than 40% of the world’s advertising by value takes place online and a handful of large players have a commanding position.4 Between them Google and Facebook are expected to make $171.1 billion in advertising revenues in 2019, 51% of the total digital spend.5 By providing free and low-cost services on proprietary sites (‘platforms’), Google and its competitors and collaborators gain access to vast amounts of information about vast numbers of individuals. They analyse this data and use it to inform efforts to modify our mental states and our behaviours. Clients then pay to reach ever more precisely described, and intimately understood, sub-groups within the platforms’ gigantic user base.

The companies are always looking for new ways to extract more, and more detailed, data from their users, and for new ways to generate insights from it. The need for more data helps explain why they are moving into fields as diverse as crypto-currency and urban development.6 The need to make more sophisticated use of it helps explain their lavish investments in artificial intelligence. It is in their interests to promote engagement and interaction, to elicit the disclosures that are their raw material. As a result almost all aspects of human sociability, of the life of the species, are now shadowed by digital architectures. These architectures promise, and indeed often deliver, user benefits. But these benefits are secondary to the business model, best understood as a combination of surveillance and manipulation.7

The platforms mainly cater to the needs of corporate advertisers but they also count political propagandists and election strategists among their clients. At the same time they are now leading providers of news and current affairs and important producers and distributors of entertainment. A distinct new media regime is supplanting broadcast-plus-print as the means by which the social order becomes visible and intelligible.8 So far the leading players in this new regime have avoided the formal regulation and legal responsibilities that apply to broadcasters and print publishers. But elected representatives and the remnants of the pre-internet media sector in the US and the UK are agitating to secure a privileged position in any future media landscape. The current debate about ‘fake news’ and foreign subversion is part of a process, already far advanced, of ensuring that the digital media serve the same, essentially conservative, function as the outlets they are displacing.9

None of the dominant players in the current economic order have any desire to see the emancipatory potential of digital media realised. Needless to say, those tasked with defending the status quo already take a keen interest in the platforms. US-UK State intelligence agencies now have direct access to the data generated by Facebook, Google et al. Indeed, their infiltration of, and substantial integration with, the digital communications architecture in many ways recall earlier efforts to bring both newspapers and broadcasters into their orbit.10

Our activities online are subject to unseen and unacknowledged supervision by employees and automated processes. While we can interact with others, we do not fully understand, and certainly do not control, the terrain on which we do so. And even when we can share our responses to events with particular communities of knowledge, we have no independent means to reach others outside them. Commercial platforms cannot prioritise the ideals of a liberal public sphere, much less the principle of popular sovereignty, over the profit motive. The need to prolong and deepen our engagement with the platforms must come first, even if it means that isolated and vulnerable individuals are exposed to misleading, hateful or distressing content.

Human sociability more generally relies on digital mediation to a far greater extent than it did a generation ago and, again, this digital mediation is for the most part shaped by commercial logics. The platforms are becoming sites of addiction and compulsive use and there is little scope to develop ‘public service’ interventions, let alone more radical forms of democratic control.

The fusion of the sales effort with news and entertainment content is by no means new. And attempts to enlist the dynamics of social life to the task of persuasion are a constant theme in modern propaganda. In the 1950s the American sociologist C. Wright Mills noted the desire of powerful groups to gather knowledge to inform efforts at covert control:

To change opinion and activity, they say to one another, we must pay close attention to the full context and lives of the people to be managed. Along with mass persuasion, we must somehow use personal influence; we must reach people in their life context and through other people, their daily associates, those whom they trust: we must get at them by some kind of ‘personal persuasion’. We must not show our hand directly; rather than merely advise or command, we must manipulate.11

Nevertheless the extent to which the platforms separately and together constitute habitats, the elements of which can be arranged and rearranged at the whim of their owners, must make us pause. If it is true that media influence is qualified, and to some extent counteracted by the social contexts in which individuals are shaped and reshaped, then the platforms’ ability to exercise unseen control over these processes of socialisation suggests that they possess new capacities for manipulation.12 Friends and family can be made to serve as vehicles for paid-for content on an unprecedented scale; our wider social networks can be made up of deceptive and malicious actors; our ideas of what constitutes ‘common sense’ can be algorithmically steered towards hair-raising extremes.13 The picture is further complicated by the activities of well funded and highly motivated groups who use the dynamics of social interaction to radicalise others.

There is no shortage of reporting on the power and reach of the advertising platforms, the pathologies associated with social media use, and the malign possibilities created by the capture and analysis of behavioural data at scale. Although the picture is distorted by vested interests it is obvious that we cannot leave the preeminent means of public communication and social coordination in the hands of a few private corporations and their partners in the secret state.

The Limits of Liberal Reform

Many of the responses to the emerging reconfiguration of global information flows leave this partnership between private and secret interests more or less unscathed. Taxing Google and other companies to fund public service journalism depends on their continued, massive profitability, and so would further entrench them as foundational institutions in the emerging, digitally mediated social order.14 The idea of a ‘data dividend’ - payments to individuals for their information - also presupposes that personal, intimate and politically sensitive data will continue to be collected in vast quantities by the leading companies and then monetised.15 Unionisation of the tech sector, while desirable in itself, will not be enough to change the relationship between the leading firms and the rest of society.16

Attempts to apply the principles of American Progressivism to the digital sector run into similar problems. Elizabeth Warren’s proposals to regulate the digital giants have some merit but a world where, for example, Instagram, Whatsapp and Facebook are owned by separate corporations is still a world where massive corporations generate vast profits through surveillance-and-manipulation. While making the digital sector more competitive in certain respects, Warren would leave society’s most important communicative resources in private hands.17

The imposition of data portability and interoperability in functions like instant messaging would deliver real benefits to consumers. But even in a ‘redecentralised’ system we will remain consumers rather than citizens: we will still choose between competing firms in a marketplace when deciding how we will conduct our lives online. In such circumstances network effects will still favour scale, and free services funded by data harvesting and advertising will still tend to win out over paid-for options.

Scale isn’t something that should trouble us in itself. The mystifications that flourish in the mainstream of the current, state-corporate media system can only be challenged and dispelled if the online spaces most of us use are subject effective democratic oversight and control. And the collection and analysis of data from very large platforms will be an extremely important aid to the work of democratic planning. In other words, both political and economic emancipation depend on building a public network architecture that rivals the size and sophistication of the private platforms. Capitalism can survive challenges from the margins. Indeed it draws both legitimation and profit from them. Its most sophisticated partisans have always understood this. Our task is to bring revolutionary imagination and post-capitalist practice into the broad daylight of the everyday.

The Need for a Socialist Response

We need to develop a distinctively socialist response to the emerging digital organisation of communications. Working from a presumption in favour of commonly owned and managed resources and democratic governance, we can begin to outline a digital sector that provides the infrastructure for a much broader process of democratisation.

Our ultimate aim is to establish democratic deliberation as the central method for allocating material resources and social goods. This requires that we reduce the importance of markets, and market-mimicking or market-anticipating institutions, and that we greatly enhance the powers of the citizen body. Large-scale, state-level planning decisions can then be made intelligible to the public and, as planning becomes more detailed, individuals and self-self-organised groups can take the lead in decision-making until the glamour of the commodity working on isolated individuals is replaced by a conversation between demystified citizens. Instead of a few all-knowing centres surrounded by manipulable masses, each of us secures the means necessary for clear-eyed decision-making about our needs and wants, and about the balance to be struck between them. In other words, the assembly displaces the marketplace - both in the digital sector and in the broader political economy. This will only be possible in an information environment characterised by equality-in-speech and rules-based participation in public business.18

If we do not adopt a decisively democratic and socialist approach to digital technology we will be drawn into an exhausting struggle for what will only ever be minor adjustments to the status quo. In this struggle the companies will marshal vast lobbying resources while we will be denied the only possible countervailing power - the charisma of a transformative agenda. In the next section I trace the outlines of this agenda.

A Socialist Agenda for Digital Technology

It is inconceivable that we should allow so great a possibility for service, for news, for entertainment, for education, to be drowned in advertising chatter.

—Herbert Hoover

We do not have to believe that the new, digital iteration of capitalism marks a radical departure from what preceded it to recognise that technology creates new opportunities to exert unaccountable power, and new opportunities to strengthen democracy. A socialist government that takes this state of affairs seriously will use public investments to create democratically managed resources and commonly held properties in the sector. The immediate goal is to break the hold of the surveillance-and-manipulation platforms over citizens who aspire to self-government. This public claim on the central means of communication also creates potential for democratisation throughout the social field. The formal constitution and key aspects of the informal order underpinning it, such as land and credit, stand to be transformed by changes to how they are described, and by changes to the distribution of those descriptions.

Platforms of Our Own: Reithbook and Beyond

As a first step, we need to create public platforms on which commercial imperatives will replaced by clear principles of communicative equality. These include: a right to attend to one’s private affairs, and to participate in public life, without harassment or surveillance; an equal power to make our world-view, experience and interests into matters of general consideration; a corresponding power to challenge and disarm efforts at manipulation. Citizens must be able to access and share publicly relevant information, publish their responses, and have their responses assessed in turn, confident that, to the extent that they are vulnerable to manipulation, they have the means to combat it. In practical terms this means developing interoperable social media and messaging resources, as well as secure data storage for individuals and groups. These resources will need to be tied to a broader reform agenda that includes changes to the structure of the BBC and direct control by individual citizens of public subsidies to support journalism. They will also need to bring the public into their governance through random selection, election and general participation based on the rights outline above.

Instead of relying on an environment designed to deliver advertising content to targeted demographics, we will be able to shape our online experience and collaborate in efforts to understand and change the world. We will share information consciously and be able to access and analyse collectively generated data as equal citizens. Designers will be able to concentrate on promoting sociability and productive exchange, without the need to extract and analyse data for the purposes of manipulation. Any use of algorithms will be open to scrutiny and public oversight. A democratically brokered consensus will take precedence over the promotion of engagement at all costs. Wherever possible, this socialist programme will adopt and adapt free and open source material. (We might decide, for example, that the Decidim platform in Barcelona, for example, delivers much of what we want from a public platform as it relates to political decision-making.19 )

By working at a national scale we will be able to establish a public option as a central part of our online experience. A public platform will connect us to content from the BBC, from museums, theatres and galleries, from archives and libraries. Public institutions will become platforms in their own right that also connect with others. An individualised system for distributing public subsidies for journalism and research will find a publishing outlet on these platforms. This content and the debates that surround it can then be made to mesh transparently and according to well understood principles with the output of the BBC.20 In this way public service values at the BBC will be supplemented by a more kinetic, and mutually rewarding, relationship between the institution and the audiences it serves.21

Attempts to misinform or mislead the public will be subject to sustained challenge by organised and articulate publics. This will make powerful institutions more transparent and bring the citizen body as a whole into sharper focus, while making individuals less vulnerable to data harvesters. Self-organising networks will be able to create their own sub-platforms and shape their functionality to serve particular needs and interests.22 Each of us will be able to engage as members of a range of collectivities. Rather than a single site, this platform architecture will provide us with a profusion of spaces that overlap in diverse ways. Public sector institutions, including local, regional and national government, will provide venues where citizens and more or less cohesive groups can assemble and secure a claim on the political.

We will be free to use commercial platforms, of course. But the surveillance-and-manipulation business model means that these cannot make collective deliberation and agenda-setting their priority. Advertisers prefer to work their magic on isolated, and preferably anxious, individuals who can be persuaded that competition and consumption, not collaboration and conviviality, are the answer to their troubles. And in an environment where willingness to spend money translates directly into communicative reach, the citizen body as a whole and in all its diverse constituent elements tend to be marginalised by concentrated capital.

For the same reason the commercial platforms promote a highly restricted version of the social. The competitive need to generate insights about consumption-oriented subjects, taken to its limit, leads to a joyless and resentful scrolling through, more or less artificial, images of social success and connection. Resources we control, on the other hand, will enable us to find one another in diverse ways, and to delight in the full potential of our sociable natures.

We can be confident that a public option in social media technology will serve our needs better than its corporate rivals in other respects. Being able to live as civic and social beings without being subject to panoptical oversight and surreptitious direction by private and secret interests will provide an important respite from the commodification of life processes pursued by the leading capitalist enterprises. While it is utopian to imagine that we will be able to prevent abuse online, users and technicians working cooperatively to reduce the impact of insincere and malicious speech will not need to worry about protecting a business model that demands engagement at all costs.23 Indeed, we will be able to participate in a conversation about what digital technology is for, and what its limits should be. Platform design could then be used to encourage real-world engagement and association and we could even devise ways to reduce the net amount of time we spend staring at screens.24

The value created by the users of the private platforms is captured by owners and advertisers. The platform architecture proposed here will return that value to the citizen body in the form of a better understanding of the social world, and greater power to address problems within it. The relationship between the social, the political and the economic can be renegotiated in ways that do not accept the limits now imposed in the main circuits of communication. The public platforms will give the majority the means to resolve conflicts and pursue shared interests, in much the same way that elite media and elite sociability have historically served the ruling class. At a maximum, this public communications system would make the best available account of the social a shared point of reference in politically consequential speech.

The creation of this collection of public digital resources does not only threaten the interests of the digital giants. Newspapers and broadcasters have long benefited from the restrictions imposed on public curiosity by insiders. A genuinely public platform, designed to function as a collection of spaces for collective sense-making, will transform the terrain on which all content providers operate.

The elite vetoes that frustrate moves towards general enlightenment will be overruled at last by a public communications system that privileges democratic speech over the claims of property and its paid-for experts and apologists. Journalists and researchers will be gradually drawn out of patronage relationships with institutional superiors and owners and into a dialogue with their audiences. In this way the tight control of political speech by private and secretive actors will give way to a much more plural, open and reflexive public sphere.

As the state democratises it will need a digital architecture that maps onto its changing structure. More extensive participation in the political process can then be publicised according to clear and consistent rules in order to benefit those who are excluded from decision-making in the current order. The result will be better decision-making as the quality of general invigilation improves.

It is particularly important to bring the population into a dialogue with public institutions when the state is expanding into areas that have been left to the private sector in the recent past. For example, public banking will need detailed information about social priorities if it is not to be captured by those few institutions capable of making themselves intelligibly present in the existing state settlement. The arterial supply of credit requires capillary networks of insight and assessment if it is to find its way back to the National Investment Bank and its regional subsidiaries as repayments on viable investments.

Governance Online

We will want to supplement the public platform architecture with specialised software that makes the public sector more transparent and accountable. In this we will again be able to draw on resources from Barcelona. For example, the City Council there has established an open digital marketplace to make public procurement more accessible to local startups and small and medium sized firms. This could be adopted here to promote community wealth building along lines pioneered in Preston.25 If citizens’ assemblies are to become an ordinary feature of public life, they will also need a digital infrastructure to support their work and integrate their proceedings and recommendations into the wider field of publicity.26

An expanded co-operative sector will also benefit from new forms of online, as well as real world, governance. Members need to be able to access information and express their preferences in secure conditions. Without new capacities for general oversight and effective and rewarding participation there is always a danger that insiders will use their information edge to secure corrupt benefits. A reforming government will no doubt want to legislate to make it simpler to form co-operatives. But it will also want to ensure that publicly funded digital resources are available that give power to workers and consumers.27 New institutional forms, such as public-common partnerships, will also need to be supported by technology so that their democratic potential is realised through sustained and broad-based participation.28

Similarly, voluntary organisations and charities stand to benefit from more democratic governance. Large institutions in particular will benefit from forms of online governance that bring them more firmly under the supervision of their members. At the moment too much of civil society operates as a kind of genteel racket, in which the generous and humanitarian impulses of mass memberships are converted into lavish lifestyles for a few senior managers. Where charities receive public funding it might be desirable to insist that they adopt defined standards of democratic governance supported by digital resources so that they can act as models of egalitarian transparency. At any event, the socialist project aims to reproduce the values and structures of a democratic state throughout society, and digital technology will play an important part of this process of diffusion.

E-Commerce: From PayPal to PayPub

Platform retail has proved extremely successful and seems to follow much the same logic of market concentration as the advertising platforms. One company, Amazon, now accounts for half of all of online retail in the US, and for $7 of every $100 spent by US shoppers.29 The information it captures from its operations means that Amazon can now exercise enormous power throughout the supply chain.30 It has also become a leading provider of computer services and is putting together a portfolio of sites from which it can extract commercially valuable data.

It is important for the state to develop an online payment system as part of its public banking infrastructure. This payment system, supported by e-commerce authoring tools that are compatible with the rest of the public platform architecture, would integrate with a renationalised Royal Mail to provide individuals and businesses with a publicly accountable alternative to Amazon and Ebay. Publicly owned and cooperatively governed e-commerce promises lower costs of intermediation and transparent and equitable terms of service. Whereas Amazon tracks sales categories and manufactures items designed to compete with the businesses that use its platforms, this approach will provide transparent and equitable terms of service to consumers and producers. A public e-commerce option might also be able to favour local, ‘onshore’ production over transnational corporations based in secrecy jurisdictions by imposing a duty of candour on vendors.

This retail platform, when combined with other investments in technology, establishes the conditions for a much more extensive democratisation of the economy. As real time behavioural data becomes available to the population at large, rather than a relative handful of network managers, consumers can combine to access goods on equitable terms with producers. Indeed, production, which is already informed by intensive surveillance of consumers, could take a much more collaborative form. Demand would be discovered in undistorted discussion between civic equals, who would then find the material resources and labour power needed to satisfy it.

Taken as a whole, the public platforms will allow citizens to make economic decisions on the basis of better information and at a remove from the needs of the moment. Patterns of consumption that compensate for powerlessness will be redirected towards ends that are discovered through collective deliberation and reflection. The sales effort gives way to the public discovery of needs and wants, and the balance to be struck between them.

Socialise All Rents!

Wherever possible, a reforming state will want to reduce monopoly rents and compulsory charges in the economy. Our agenda for the digital sector would therefore include a suite of publicly owned and democratically managed software resources. At the outset this would include enterprise and operating systems based on existing free software resources - publicly funded and maintained versions of Linux, Open Office, and so on. Small businesses and the self-employed will immediately enjoy lower overheads and public sector organisations will benefit from enhanced system security and reduced operating costs.The state’s ability to establish standards across its own institutions means that it has enormous power to stabilise and promote a low-cost system architecture.31 A publicly funded development platform could allow independent operators to add to the share of free resources and provide a structure of payments that rewarded valuable innovations without resorting to the market mechanism.32

There are many other areas where the public sector can strip out rents. It ought to be possible to register URLs at very low cost and to access web design tools paid for by the public sector. There is also a case to be made for public and collaborative search and reference capabilities, especially if they are tied to academic publishing platforms and a reinvigorated library sector.33 Web browsers would bring these functions together in a way that would make possible a host of challengers to Google organised on regional, national, institutional or sectoral lines. Rather than seeking to maximise their share of global attention each of these search-browser combinations could concentrate on serving the specific needs of particular groups while contributing to a shared stock of resources.

The design of algorithms has, to date, been dominated by commercial and military, rather than social, values. A public programme of investments would build democratic principles and conscious participation by citizens into this and other forms of high end computing. The awesome computational power currently in private and secret hands will become available to citizens where it can be used by individuals and collectivities to create new kinds of knowledge and hence new capacities to act. In this way economic planning will ultimately be devolved to individuals in free assemblies and given a properly civic character.

This standardised and stable free software architecture, combined with the other capabilities outlined above, would be available at cost to other countries. Socialist technology would then provide an alternative to an emerging duopoly in which we have to choose between American and Chinese styles of surveillance-and-manipulation.

Where Are We Going? Digital Resources for Democratic Planning

Other services currently offered by the surveillance-and-manipulation firms such as mapping can be reimagined to deliver greater public benefits. For example, a government seeking to reshape the built and natural environment will need popular constituencies to displace concentrated private interests as the lead actors in the land economy. The gathering climate crisis requires something like a process of disenclosure - a reversal of the privatisation of the countryside that marked the beginning of English capitalism. Public mapping, through which representations of physical space are tied to public databases of ownership, permitted use, hydrology, soil quality etc., can help citizens to understand the places where they live more fully and to take a more active role in planning their future. The 3-D design technologies currently used by property developers will, once made generally available, greatly assist in this work of democratic place-making. Similarly, publicly owned augmented reality holds out the promise of making the places where we live more legible and informative, and hence more conducive to both real world sociability and collective direction.

Planning in the UK is bedevilled by a kind of legalised corruption in which state power forces the majority to hand over much of their income to a tiny minority in the form of interest and rent. The building that does take place promotes a landscape of car-dependent estates and out-of-town shopping centres that no one in their right mind would choose. Public mapping and design will help ensure that infrastructure investments, new technologies in construction and other interventions in the land economy track our collectively discovered priorities. Self-governing groups deciding how they want to live together will inform the industrial strategy as it relates to housing. Underused or mismanaged land can be brought into public or common ownership in an orderly way and put to use as part of a broader economic, environmental and social programme.

Building a Co-operative Economy

At the moment bank lending overwhelmingly supports asset purchases. Public finance could be used to support the creation of commonly held properties such as co-ops and public-commons partnerships with the help of publicly developed software capabilities. Public social media platforms would provide a venue for workers and consumers to find one another, develop detailed business plans and secure start-up funding from a National Investment Bank and the National Transformation Fund. Digital technology would support the process of enterprise formation from casual expressions of interest through to the creation of legally defined and democratically governed operations.

For example, small batch and bespoke manufacturing production is becoming increasingly expensive to source from foreign markets. The state can facilitate a programme of re-industrialisation that grows the co-operative sector and deepens workplace democracy, while driving up real productivity and greening the economy. Through a conversational partnership with public bodies, organised labour can take the initiative without the enervating approval of private capital. The knowledge accruing to the public sector would enable it to make targeted investments to complete supply chains and bring key technologies into production. An entrepreneurial state indeed.

As part of this process, the public platforms will need to provide crowd-funding capabilities that help direct the attention of technocrats and elected officials away from the heavily promoted proposals of large corporations and their lobbyists, and towards initiatives that recommend themselves to the people who will, one way or another, pay for them. Villages and towns, cities and regions, as well as currently disaggregated fractions of labour, would use a variety of publicly funded and owned digital resources to develop their own plans, engage with the institutions of an expanded public sector, and create the organisational forms they need.

Industrial Strategy: Research, Development, and Production

For the most part the state’s role in the economy is ignored or disparaged, the better to ensure that its contribution can be captured by a handful of privileged private interests. But it is responsible for the bulk of the research and development that drives private sector innovation, either directly or through the use of subsidies.34 A publicly owned digital architecture would be part of a new approach, in which the state as patron plays a much more active role. This digital architecture would hep integrate research, development and production so that the implementation of new technologies tracks the public interest - through state ownership of publicly funded innovations, through free diffusion into the global intellectual commons, or through the creation of co-operative forms that subordinate market logic to social need in clearly defined ways.

For example, the UK state currently provides massive levels of support to privately owned pharmaceutical companies. This sector is able to negotiate with the NHS from a position of strength, thanks to its control of intellectual property (monopoly) rights derived to a very considerable degree from these same subsidies. Public funds end up gravitating towards a narrow range of patentable chemical interventions on inert individuals, and away from social and collective approaches that enlist the individual as a collaborator in their own wellbeing. Where innovation does occur, the financial upside is captured by a handful of global companies, whose legal structure and business model makes them incapable of acting in a public-spirited way.

Rudolf Virchner once wrote that politics is medicine at scale. The vast material and intellectual demands of modern medicine mean that it is an inescapably a branch of the political. We are now in a position to develop technologies that prevent it from serving oligarchical interests. A platform architecture of the kind outlined above will be key to liberating the sector, in that it will provide us with a space where the nature of human flourishing can be discussed in ways that do not privilege the needs of powerful interests.

In a democratic and socialist approach to healthcare, citizens with defined communicative and political rights form collectivities in which they seek to promote their own wellbeing. Data is pooled for clearly defined ends, according to generally understood principles. Experts, including medical experts, are brought into partnership with these collectivities on terms of civic equality. Rather than treating populations as the raw material for research, these experts help the rest of us to define what human flourishing looks like and to secure it. The entire process of research, development and production remains in public hands. Democratic oversight, rather than the profit motive, becomes the driver of innovation and the guarantor of efficiency.

This collaborative approach holds out the prospect of more rapid progress in pharmaceutical medicine. But once the social and economic determinants of health are given due weight, and commercial considerations no longer inhibit the clinical imagination, a much broader horizon of possibilities opens up. After all, cures are much less lucrative than symptom management. Meanwhile, the citizen’s experience of an increasing power over their own circumstances becomes inseparable from the therapeutic process.35 In healthcare and other sectors such as housing there is a long history of topdown provision from both the state and the private sector. Digital technology has an important contribution to make in efforts to establish the citizen body as the decisive actor in publicly funded innovation.36

An integrated approach to population health would have important implications for the food economy. And, as noted above, if the UK is to play a full and equitable role in moves to address the climate crisis we will need to develop new technologies that make much more efficient use of natural resources. Efforts to bring land into more productive use will rely heavily on the kinds of coordination made possible by digital technologies.

If we are to be well nourished in the future we will need to be able to identify suitable land, bring it into public and common ownership through legislation and purchase at fair value, and develop highly productive, highly diversified networks that substantially de-commodify the food economy while reducing carbon use. This might require investments in manufacturing technologies that track the needs of small, independent and interdependent growers, rather than those of industrial agribusiness and national retail chains. Efforts to increase yields from the UK’s home waters will also require investment in new kinds of social coordination as well as physical infrastructure.

The restoration of pre-enclosure patterns of land use and a new relationship with the sea together promise abundant food. Massive public health gains can be made through the self-conscious creation of a patchwork of new and revived food cultures across the British Isles. But all this needs to be knitted to a social order characterised by collective deliberation and shared powers to frustrate manipulation. At the moment this might seem a distant prospect. But however unlikely it sounds, it is necessary if these islands are to support a population in the tens of millions a few decades from now.

Public investments in digital technology are a necessary component of an industrial strategy that serves the majority. This is in part a matter of preventing insiders from securing corrupt advantages. In part it is a matter of bringing the public into the development process as active participants with a direct stake in projects. Above all it is a matter of acknowledging that technological development is shaped by the power relations that surround it. Unless innovation is embedded in a culture of democratic oversight and direction it will never deliver on its emancipatory potential.

Digital Socialism

A socialist approach to digital technology aims to help democratic assemblies meet human needs and wants with more granularity and sophistication than the market. A fully constitutionalised digital sphere, rather than the corporate boardroom, becomes the central space in which economic planning takes place. Preferences that are currently revealed through our guileless online activity are discovered instead through reflection and deliberation on the basis of the best available information.

By changing the process of discovery we change the nature of the preferences discovered. Instead of acting as mystified consumers, we make choices in a state of disenchantment. What is kept hidden in commercial culture - the range of possibilities beyond individual consumption, the full implications of particular choices and styles of life, the tendency towards magical thinking encouraged by the creation of the commodity form itself - can be acknowledged and taken into account. What is currently unspeakable becomes available as a matter of public business.

The Case for a New Institution

If you want to do something new, set up a new unit, and recruit. You’ll get people joining who want to do new things.

—Michael Jacobs

Some people might accept the need for the public sector to take a more active role in developing digital technology but reject the idea of a new institution. After all, a constellation of government departments and parastatal organisations already exists and might be able to do the necessary work. But reliance on what already exists would be a serious mistake for a number of reasons. For one thing, we are faced with overlapping economic, social and environmental crises, all of which require new technological resources if they are to be addressed. The existing institutional array was designed for a different time, with a different set of agendas, and with different operating assumptions. A new, generously funded organisation allows us to start afresh, on a scale, and with an urgency, equal to the task.37

The need becomes more pressing when we factor in resistance to far-reaching changes to the structure and purpose of the state. Ralph Miliband once warned that ‘to achieve office by electoral means involves moving into a house long occupied by people of very different dispositions - indeed it involves moving into a house many rooms of which continue to be occupied by such people.’38 Electoral success secures control of one, very visible, piece of the state apparatus for would-be reformers. But much of the rest will be staffed by people with very different ideas about the purpose of public intervention in the economic sphere, about the practicality of democratic self-government, and about the primacy of private capital. Career progression has depended on working effectively and creatively within a governing logic established by Thatcher and elaborated by her successors. While many individuals will welcome the opportunity to think and act more expansively, some will not, and resistance to any reform agenda will tend to intensify as one moves up the various hierarchies.

After forty years of neoliberalism public institutions need to be restructured along lines that combine democratic legitimacy with technical expertise and efficiency. This does not mean a simple reversion to principles of Keynesian public service. Rather, the public sector must develop an approach that enhances the capacities of the citizenry in assembly. The focus shifts from the minister of the crown to the body politic as whole.39 This approach will help secure the state from subversion by sectional interests, and model a wider shift in the economy and in society towards more egalitarian practices and a more equitable division of wealth and power. But this amounts to a new logic of state. It will need novel institutional contexts in which it can be elaborated and refined. Just as the British Broadcasting Corporation provided a template for the institutions of the postwar social democratic settlement, the British Digital Cooperative (BDC) is intended to lead the way in developing the structures of democratic socialism.

The supporters of reform deserve to see swift, conspicuous action, in new places, according to new principles, in the pursuit of clearly defined goals that enjoy broad support. The BDC will be able to establish development teams in towns and villages, coastal resorts, post-industrial cities and rural areas that have long been neglected. It will also be able to create new physical infrastructure to support its mission and move quickly to establish laboratories for a democratic and prosperous future.

While the creativity of start-up culture can be exaggerated, new institutions provide opportunities to escape bureaucratic organisation and the stifling effects of hierarchy. The BDC will be able to hire from the existing state and from the private sector. But it will be able to sidestep recruiting norms that filter out potentially valuable workers, and to experiment with new forms of workplace organisation. It will also be able to try out new ways of contracting labour from a global pool of talent through mission prizes and remote working. After the shambles of the Brexit referendum and its aftermath, the BDC will demonstrate Britain’s openness to the world in its structure as well as in its mission.

A new institution offers skilled workers a chance to escape the stultifying demands of venture capital. Technicians and software engineers who have been encouraged to think in terms of an IPO or a Google buyout will have a chance to put their talents and energy to use creating a new economic and political order, compatible with the survival of human civilisation at scale. People are all too easily demoralised and depressed by the small-mindedness of neoliberal ambition. The BDC will be a place where people can live well and be celebrated for their contribution to the common good. And an institution founded with an explicit mission to promote democracy will be better able to resist those who want digital technology to remain an instrument of oligarchic domination than institutions predicated on the idea of ‘smart’ collaboration with transnational capital.

The BDC is an opportunity to break with the chauvinistic and status-obsessed culture of parts of the technology sector. As a public institution with an urgent mission the BDC will be able to combine accountability and the highest standards of workplace civility with intense creativity. Relatedly, the BDC will also be able to develop novel relationships with the end users of its products. This is a chance to tie research teams to co-designing publics so that innovation tracks the expressed needs of the citizenry on which it depends. In this way the BDC will model a relationship between public expertise and the citizen body that will become more familiar as the UK becomes more fully democratic.

A new institution begins without an accumulation of internal assumptions and unspoken taboos about who can, and cannot, contribute and how. It provides an opportunity to think creatively about how to give expression to fundamental principles and values while addressing vitally important problems. Justice and the demands of the moment call for an institution in which talent, public spiritedness and achievement count for more than cultural capital, seniority and conformity. By establishing the BDC on these lines we will present both a template and a challenge to the rest of the state.

Operating away from the metropolitan core the BDC will be able to develop a different understanding of the UK’s political economy and its various potentials, and work with local government and other institutions to ensure that reindustrialization does no simply add to the advantages enjoyed by London and its periphery. It will also be able to assemble land and properties so that the uplift from local economic growth can be captured for the public and it will be able to work with other institutions without the burden of a shared history. Crucially, people will learn to exercise new powers through their participation in the democratic structures of the BDC. It is to these structures that we now turn.

Building the British Digital Corporation

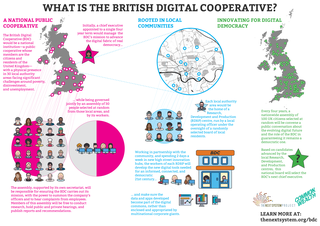

We will establish a British Digital Cooperative with a mission to develop the technical infrastructure for economic, political and cultural democracy.

—Manifesto of a reforming administration

Notes on Structure

The transformative mission of the British Digital Cooperative (BDC) must dictate both its structure and spatial organisation. Legally it will be established by Parliament as a public cooperative whose members are the citizens and residents of the United Kingdom. The responsibility for managing this cooperative will be borne jointly by its workforce and by the public. The powers of the latter will be exercised by assemblies formed through random selection.

Parliament will create this public cooperative with a mandate to develop the infrastructure of a more complete social, economic and political democracy. It will impose a particular duty on the BDC to establish working relationships based on civic equality. In the first instance the Prime Minister will appoint a chief executive to deliver on detailed articles of instruction that elaborate on its fundamental mission. The chief executive will serve for a single four-year term. They will appoint an executive board and after one year a quarter of these board members will be elected by the workforce.

The chief executive will be required by statute to convene an oversight assembly of thirty people selected by lot from one of the local authority areas in which it operates. All assembly members will be paid at the national living wage for the equivalent of one day’s work per week. They will serve one year. This assembly, supported by its own secretariat, will be responsible for invigilating the operations of the BDC to ensure that it meets the obligations imposed on it by Parliament. It will have general powers to summon the company’s officers and to hear complaints from employees in confidence and representations from the general public. They will be free to conduct research, hold public and private hearings and publish reports and recommendations.

The first chief executive of the BDC will establish Research, Development and Production (RD&P) centres in severely deprived local authority areas. The physical geography covered will include cities, towns, villages, coastal resorts and rural areas. Mirroring the national structure, the centres will have an operations officer, an executive board and an oversight board selected by lot from local residents. These assemblies will be responsible for ensuring that the BDC acts in accordance with its statutory responsibility to promote working relationships based on civic equality. They will also be responsible for establishing and testing the governing principles of the platform architecture as it relates to privacy, civility, security and so on.

Product design and development will be structured as a partnership between the BDC and the communities in which it is based. Technologies will meet the needs, and defend the interests of citizens, in part because citizens will be involved throughout the development process as both participants and invigilators. Through their involvement in product design, residents will be familiar from the outset with the potential of new technologies to build community wealth. The centres will act as transfer points for new skills and capacities and the duty to promote equality will require them to establish educational projects wherever they operate.40

The RD&P centres will have a defined mission under the articles of instruction and will be free to establish subsidiary institutions, including land trusts, to ensure that they meet their objectives in a timely and thrifty manner. They will liaise with public sector institutions to improve the physical infrastructure for data collection, and to develop municipal resources. Local public sector institutions will have defined rights to representation on each RD&P centre’s consultative boards.

Each centre will also be required to establish ‘high street hubs’ where the public can use free software, open hardware and other resources. BDC employees will be free to spend up to two days a week in these collaborative spaces working on their own projects, provided these are consistent with the overall mission of the BDC. Beginning with these production hubs, the BDC will also experiment in ways of using technology to promote diverse forms of online and offline sociability.

The chief executive will have overall responsibility for ensuring that each centre meets its obligations under the articles of instruction, and for ensuring that all technologies are deployed in ways that maximise the public good in a manner defined by statute. They will decide how to spin out new institutions and promote the work of the BDC nationally and internationally. They will maintain an overall view of the centres’ projects and to ensure that, wherever possible, resources are shared between centres. They will also be required to build and maintain connections between the BDC and the rest of the public sector. Their office will ensure that, wherever possible, the BDC proceeds by adapting existing free software resources in a way that helps socialist and non-profit projects worldwide.

Operational details are beyond the scope of this paper, but the chief executive will want to draw on best practice in the private sector and in civil society to ensure that the collection of public resources envisaged here starts with what John Gall called ‘a working simple system’ and grows rapidly to achieve considerable scope and sophistication. The emphasis on adopting and adapting existing open source and free software resources means that the BDC won’t be tempted to develop ‘a complex system designed from scratch’ which ‘never works, and cannot be made to work.’41

In the fourth year of their term the chief executive will convene a large assembly drawn by random selection from the UK population. This 100-person assembly will draft new articles of instruction within the terms established by statute. It will sit for six months and take evidence from staff, from the other BDC assemblies, and from the public. Its deliberations will be public and the new public infrastructure and the other digital resources outlined above will bring the drafting process to the attention of a large and engaged audience in the UK and beyond.

In this way, every four years the BDC will host a widely shared discussion about the future of the digital sector, which will shape its operations for the next four years. This conversation will inform the country’s broader industrial strategy by providing a venue in which organised labour, the cooperative sector, private industry and other interests can articulate their needs in a manner that the public can understand and assess. The BDC will be mandated to give the deliberations of the large assembly due prominence in the communicative resources it controls.

Once new articles of instruction have been published, all candidates for chief executive will be interviewed by one of the RD&Ps’ assemblies, which will send a confidential note to the large assembly. The large assembly will interview the candidates it wishes to consider. It will then appoint a chief executive to a new four-year term. Past service to the public and a plausible agenda for the future will count for more in this selection process than a talent for office politics.

The large assembly responsible for appointing the chief executive will meet once a year during their term to receive a report on progress, hear representations from the workforce and the public, and to publish their own findings. During this time it will also confer honours on employees and citizens nominated by the various other assemblies.

If the first oversight assembly decides that the BDC is failing to pursue its articles of instruction with sufficient vigour it will be able to begin recall proceedings against the chief executive. If the move to recall is confirmed by the large assembly, the chief executive will be removed and the workforce will elect a replacement for the rest of that term.

Funding the British Digital Cooperative

The BDC will be established with a grant from the National Transformation Fund. It will also be responsible for administering the revenues from any charge on broadband or mobile internet access.

Infographic: What is the British Digital Cooperative?

Conclusion

A reforming administration in the UK will only succeed if its aims and methods are understood by the public. It is therefore vital that we transform the emerging, digital terrain on which the social and political spheres become available as objects of thought. This is not to argue for state control of the media or anything like it. Indeed, the first task of the British Digital Cooperative will be to establish the conditions in which broad-based and consequential participation in public speech become possible - precisely so that citizens can hold the government to account.

The BDC is intended to operate as a vanguard institution in a number of other ways. It will provide an opportunity to establish new working cultures, new partnerships between the technology sector and the wider public, and new opportunities for civic excellence. It will create digital resources that help the public sector to become more dynamic and responsive, and it will ‘spin out’ technologies and organisations that combine democratic, cooperative and public service values in new ways. Its structure will provide a template for other public sector and civil society organisations.

The BDC is intended to bring the insights and experience of large numbers of people into contact with skilled workers who are motivated to serve the interests of the citizen body as a whole, rather than an opulent or well-connected minority within it. We cannot predict in detail what it will achieve. But it will give us the means to make what is now necessary possible, before it is too late.

- 1I would like to take this opportunity to thank some of the people who took the time to help in the preparation of this paper. They include Joe Guinan and Sarah McKinley at the Democracy Collaborative, Jan Baykara of Common Knowledge, Nick Srnicek at King’s College, London, Leo Watkins of the Media Reform Coalition, and Mat Lawrence of Common Wealth. The policy seminars convened by James Meadway and Archie Woodrow in the summer of 2019 provided a welcome opportunity to discuss the broader issues of media and communications reform. I am particularly grateful to Tom Mills of Aston University and the Media Reform Coalition for his comments on the draft.

- 2Paul Sweezy and Paul A. Baran, Monopoly Capital (Harmondsworth: 1968).

- 3By manipulation here I mean successful efforts to exercise covert control over the actions of others. In the taxonomy for understanding power offered by Morton Baratz and Peter Bachrach ‘manipulation is an aspect of force, not of power. For, once the subject is in the grip of the manipulator, he has no choice as to course of action.’ See Morton S. Baratz and Peter Bachrach, Power and Poverty: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970), p.28.

- 4Stuart Thomson, ‘Internet advertising to surpass 50% of total ad-spend in two years’, Digital TV Europe, July 8, 2019 - https://www.digitaltveurope.com/2019/07/08/internet-advertising-to-surpass-50-of-total-ad-spend-in-two-years/

- 5Jasmine Enberg, ‘Digital Ad Spending 2019, Global’, eMarketer, March 28, 2019 - https://www.emarketer.com/content/global-digital-ad-spending-2019

- 6Tara Deschamps, ‘Google sister company releases details for controversial Toronto project, Guardian, June 24, 2019. Kari Paul, Libra: Facebook launches new currency in bid to shake up global finance’, Guardian, June, 18, 2019.

- 7See Shoshanna Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: 2019). Zuboff provides a detailed account of the surveillance-and-manipulation business model.

- 8The idea of a digital regime is adapted from Bruce A. Williams and Michael X. Delli Carpini, After Broadcast News: Media Regimes, Democracy and the the New Information Environment (Cambridge: 2012). Here it refers to a particular arrangement of technology, legislation, institutional forms, and social norms that combine to both permit and produce accounts of real and possible worlds.

- 9The debate about the shortcomings and excesses of the digital platforms largely ignores the extent to which the major media have always staged a production of diverting half-truths and mystifications that keep the fundamentals of political economy safe from sustained scrutiny.

- 10See Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA and the Surveillance State (London: 2015).

- 11C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York : Oxford University Press, 1956), p.302

- 12The relative importance of the individual’s social milieu and the structures of the media is much debated in media studies.

- 13This is increasingly obvious on Youtube where the algorithms’ bias towards compelling content favours the outrageous, the scandalous, and the extreme.

- 14Jim Waterson, ‘UK newspaper industry demands levy on tech firms’, Guardian, September 25, 2018 - https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/sep/25/uk-newspaper-industry-demands-levy-on-tech-firms

- 15Jaron Lanier, Who Owns the Future? (New York: 2013).

- 16US-UK defence manufacturers are often highly unionised. But for the most part workers have not been able to prevent their products from being used for the purposes of internal repression or external aggression.

- 17Elizabeth Warren, ‘Here’s how we can break up Big Tech’, medium.com, March 8, 2019 - https://medium.com/@teamwarren/heres-how-we-can-break-up-big-tech-9ad9e0da324c Even the modest benefits of increased competition and consumer choice that Warren wants to secure depend on regulators behaving with superhuman virtue.

- 18These principles are sketched in the next section. I have explored the relationship between the state form and the communications system in more detail elsewhere. See Dan Hind, ‘The Constitutional Turn: Liberty and the Cooperative State’, The Next System Project, September 7, 2018. https://thenextsystem.org/learn/stories/constitutional-turn-liberty-and-cooperative-state

- 19Ajuntament de Barcelona, Barcelona Digital City: Putting Technology at the Service of People (2015-2019) - https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/sites/default/files/pla_barcelona_digital_city_in.pdf

- 20See Dan Hind, The Return of the Public: Democracy, Power and the Case for Media Reform (London: 2011) and Leo Watkins, ‘Democratising British Journalism: A Response to Jeremy Corbyn’s Alternative MacTaggart Lecture’, New Socialist, September 12, 2018 - https://newsocialist.org.uk/democratising-british-journalism/

- 21See Tom Mills, ‘The Future of the BBC’, 15 September, 2017, IPPR; Media Reform Coalition, ‘Draft Proposals for the Future of the BBC’, 3 December, 2018 - https://www.mediareform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MRC_flyer_20180312_WEB-1.pdf. The socialist agenda for digital technology outlined here is intended to complement, and sometimes take direction from, the needs of a reformed BBC and the public sector more broadly.

- 22It is particularly important that people who are currently marginalised in the emerging digital communications regime have the means to find common cause with others and to build political power.

- 23A public platform designed on explicitly egalitarian lines, that does not need to enlist the infuriating allure of celebrity, might be intrinsically less troll-generative, who knows?

- 24I am indebted to Leo Watkins for this point. For an extended conversation about the politics of sociability, see the excellent #ACFM series from Novara Media: https://soundcloud.com/novaramedia/acfm-collective-joy

- 25Ajuntament de Barcelona, op. cit.

- 26Much of what is needed already exists in some form or another. See Alex Parsons, ‘Digital tools for citizens’ assemblies’, Mysociety, June 27, 2019.

- 27The need to constitutionalise co-operative forms on democratic lines cannot be stressed enough. Without robust defences against collusion the sector simply cannot play the part its advocates claim for it in a post-capitalist economy.

- 28See Keir Milburn and Bertie Russell, ‘Public-Common Partnerships: Building New Circuits of Collective Ownership’, Commonwealth, June 27, 2019 - https://common-wealth.co.uk/Public-common-partnerships.html

- 291. Juozas Kakiukenas, ‘Amazon Marketplace is the largest online retailer’, Marketplace Pulse, December 3, 2018 https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/amazon-marketplace-is-the-largest-online-retailer 2. Melissa Fares, ‘US retail sales expected to top 3.8 trillion in 2019: NRF’, Reuters, February 5, 2019 - https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-usa-retail-outlook/u-s-retail-sales-expected-to-top-3-8-trillion-in-2019-nrf-idUKKCN1PU1YM

- 30In fairness we should note that this is something that Warren’s regulatory reforms seek to address.

- 31This free software architecture could also encourage the manufacture and recycling of hardware.

- 32Applications available on this publicly maintained platform could be awarded prizes and ‘adopted’ by their users according to a clearly defined protocol.

- 33See Jonathan Grey, ‘It’s time to stand up to greedy academic publishers’, Guardian, April 18, 2016.

- 34See Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths (London: 2018); Erik Reinert, How Rich Countries Got Rich and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor (London: 2008).

- 35See Jeremy Gilbert, Common Ground: Democracy and Collectivity in an Age of Individualism (London: 2013) for an illuminating discussion of the relationship between agency and affect. If inequalities of power are experienced as higher rates of mental distress and illness, the other, not explicitly clinic, kinds of egalitarian organisation proposed in this paper will have considerable therapeutic value. See Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-being (London: 2018).

- 36This approach, and indeed the entire socialist agenda for technology, rejects the neoliberal notion of ‘government as a platform’, in which state investments in digital technology are intended to create ‘a more robust private sector ecosystem’. See Tim O’Reilly, ‘Government as a Platform’, Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 2011, vol. 6, issue 1, 13-40

- 37There are precedents here. The New Deal administrations created a host of new organisations, the so-called alphabet agencies, which ranged from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to projects to support the arts under the aegis of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). New technologies and industries, and the need for public intervention in existing sectors, spurred institution-building. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the Securities and Exchange Commissions (SEC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) all date back to this period.

- 38Ralph Miliband, Class War Conservatism and Other Essays (London: 2015), p.99-100. See Christine Berry and Joe Guinan, People Get Ready: Preparing for a Corbyn Government (New York: 2019) for a detailed discussion of the difficulties the existing bureaucracies present to an administration intent on serious reform.

- 39Political theory fans will recognise that the distinction here is between the Machiavelli of The Prince and the Machiavelli of The Discourses on Livy.

- 40Jan Baykara has pointed out that corporate product design is often characterised by very close collaboration between engineers and proxies for the end users. The needs of the commodity form limit the radical potential of this approach in the private sector; it need not do so in public development projects.

- 41John Gall’s warned in 1977 that ‘a complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that works. The inverse proposition also appears to be true. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be made to work. You have to start over with a simple working system.’ He is quoted in Tim O’Reilly, op. cit.