A leftward shift among Democratic presidential candidates has many pundits arguing that the rise of self-described democratic socialism will fail to appeal to voters in the Midwest, West, and South. This framework is somewhat flawed to begin with: These areas, and rural areas generally, still have substantial populations of women, people of color, working-class people, LGTBQ people, and young people who already support the Democratic Party, and in fact would be more likely to turn out if motivated with an inspirational platform.

However, it is also true that party control is aligning increasingly close to the urban-rural divide. This does not necessarily spell doom for a left-wing party, though. In fact, many red states already have some socialist policies and institutions—and not just socialist in the vernacular social democratic sense, but traditionally socialist: actual common ownership and public provision of goods and services often reserved for private markets. Not only are many of these institutions long-lasting; they’re also both popular and successful.

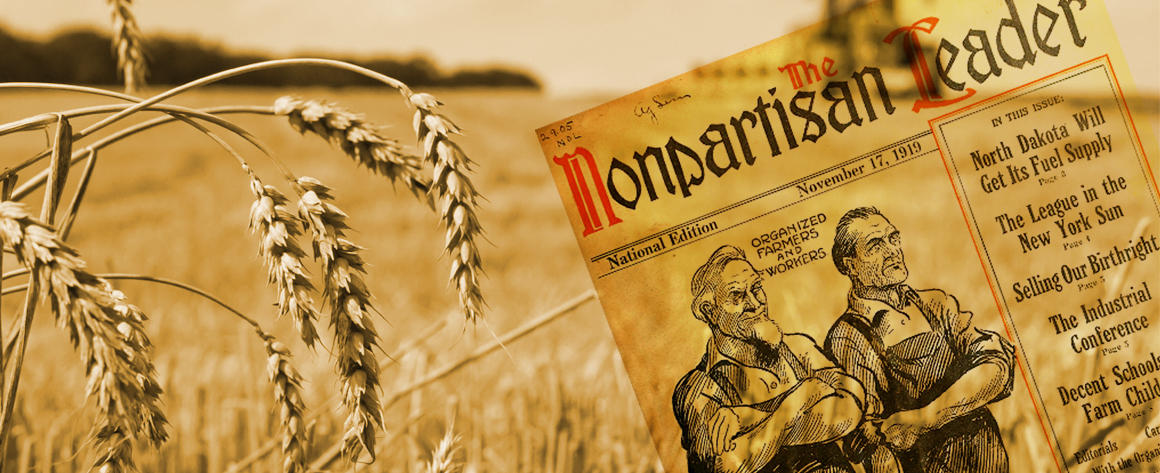

Around the turn of the last century, agrarian populists and progressive groups like the Grange and the Nonpartisan League organized the Great Plains; a multiracial populist coalition took power in North Carolina; labor militancy swept through Appalachia, and Eugene Debs’ Socialist Party presidential ticket won more than 10% of the vote in Arizona, Idaho, Montana, and Oklahoma. The New Deal won over broad swaths of society in the 1930s, and the civil rights movement created powerful progressive movements across the South in the 1960s. These movements left behind political traditions that still exist today, and in some cases continue to be represented by innovative left-wing policies that exist in unexpected places. The left has thrived before in these areas, and though it certainly won’t be easy, there’s no reason it can’t do so again.

Ownership by the people

At the same time that conservatives fear that proposals for a Green New Deal are really about “a massive government takeover of the economy,” there is already a state in the US where the government controls the entire electricity market. Nebraska’s electric grid and utilities are completely publicly and cooperatively run, offering some of the lowest rates in the country, allowing for direct community input and participation in the system, and putting excess funds back into state government coffers. In addition, roughly 20% of energy consumption in the state comes from renewables, putting it at 10th in the country.

Nebraska’s public energy system is largely thanks to the work of Nebraska’s former progressive Republican Senator George W. Norris, the same man who helped create the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The TVA also still exists to this day as a program where the federal government directly provides electricity and community development funds to over 10 million Southerners. Tennessee’s current Republican Senators both actively resist the idea of privatizing it. Though the TVA has a long way to go on its record with clean energy, it will generally be easier to move public bodies through a green transition than private, investor-owned utilities.

Tennessee has several other programs worthy of mention. Though 26 states have bowed to the pressure of cable companies in preventing the creation of municipally run broadband services, public and community internet services exist across a number of red states. Before Tennessee eventually passed such a law, 14 different towns covering roughly 342,000 people in the state’s eastern mountains established high-speed, high-quality internet networks run by local governments. The public internet services of Chattanooga and Johnson City, located in counties where 55% and 69% voted for Donald Trump respectively, were among the first cities ever to deploy 10-gigabit-per-second internet speeds. Right now, Chattanooga’s internet service is the sixth-fastest in the nation. These accomplishments show the power of municipal ownership, especially in regions like Appalachia that have been largely abandoned by private ISPs.

With Republican backing, Tennessee was also the first state to offer free community college for anyone with at least a C average and some community service. As a result, it has seen rising graduation rates and thousands of students getting an Associate’s degree without worrying about debt. Kentucky and Indiana also have similar but smaller programs aimed at educating workers in specific fields, but it’s Tennessee who is closest in the nation to the progressive vision of free college.

Though residents of North Dakota may not have free college, they can get a better deal than most. North Dakota, a state that has not voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in 55 years, is also the only state with a public bank. For exactly a century now, the state-run Bank of North Dakota has been investing in local economic development, providing reliable access to credit, and providing student savings accounts and student loans for state residents. (In fact, it was the first bank in the country to issue a federally backed student loan). The bank continues to earn a profit, most of which is returned to the state government. As part of its economic development mission, the bank also cooperates with community banks and credit unions, so that even while a few big banks have been rapidly taking over the entire banking sector, North Dakota stands out: 83% of the state has their money in either small-or-medium-sized community banks or credit unions, versus just 29% nationally.

A government-owned bank that actively intervenes in private markets seems like a conservative’s nightmare vision of socialism. But the Republican state’s bank is well-managed and serves a vital role in supporting the state’s larger economy, all while benefitting and being accountable to the people of North Dakota rather than corporate shareholders. With the success and popularity of the bank, it’s no wonder that this isn’t North Dakota’s only remaining state-owned business: the largest flour mill in America proudly advertises that they aim to “[g]row the business and provide a profit to our owners—the citizens of North Dakota.”

Credit unions are another example of common present-day institutions that are in fact quite definitionally socialist: a credit union is an organization owned by those saving their money there, meaning cooperatively owned finance. The Cold War-era idea that socialism refers to “state control” exclusively rather than any form of “public control” hides the fact that more than a third of the country already participates in one of these socialist institutions. Credit unions often offer lower rates and fewer fees, along with giving profits back to savers in the form of dividends. Many also specifically aim to serve communities in need.

North Carolina’s Latino Community Credit Union is a highly successful example despite serving a population that is 80% low-income, offering stable credit to underserved Latinos, immigrants, and community institutions. Compare this to private banks, both big and small, which charge people of color higher rates than White people and generally provide them with less access. Here’s the kicker: the top 10 states with the most of these socially-oriented credit unions include Louisiana (first place), Missouri, Texas, and North Carolina. Credit unions broadly also regularly receive support from conservatives and Republicans, including from President Ronald Reagan.

Speaking of, here is Reagan praising worker ownership of the means of production: “I can’t help but believe that in the future we will see in the United States and throughout the western world an increasing trend toward the next logical step, employee ownership. It is a path that befits a free people.”

Along with being linked to higher productivity and better pay, employee-owned businesses are the literal firm-level unit of socialism, especially when worker-owners have democratic voting powers over the business. In the more democratic worker co-ops, workers are paid standard wages and then receive their share of the business’ profit as well: one study of 450 worker co-ops found that this averaged almost $34,000 a year on top of wages.

These socialist institutions, supported by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, are not just limited to metropolitan enclaves. Fifty-one of the worker co-ops in the study above were in rural areas, not including the more than 2,000 agricultural cooperatives in which farmers collectively pool their resources. Employee stock ownership plans, or ESOPs— where workers buy out management and gradually take over a company—are even more widespread. Across just the six states of Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Texas, and Ohio, there are 2.8 million people actively working in ESOPs.

Similarly, institutions like housing co-ops and community land trusts (CLTs) provide cooperative solutions to housing that can ensure stable housing for thousands of low-income people without fear of unaffordable rents or abusive landlords. In the aftermath of the 2008 housing crisis, 4.58% of traditional Mortgage Bankers Association loans were in foreclosure; for CLTs, that rate was 0.56%. Though community land trusts are most popular in New England and the Pacific Northwest, they can be found all over the country, from Georgia to Idaho.

Other states contain their own surprises. Since 1982, Alaska has maintained a state-run sovereign wealth fund that collects part of the revenues from oil production—a natural resource belonging to the commons—and distributes them in the form of a check to every single citizen, no strings attached. (Such funds are sometimes referred to as social wealth funds.) Each year, every Alaskan gets a dividend worth somewhere around $1,000 (but ranging anywhere from $845-$2,070). Not only has this free government handout not reduced employment, but it has helped give Alaska the second-lowest income inequality and the seventh-lowest poverty rate in the nation (though poverty remains highly concentrated among Alaskan Natives, a problem requiring its own solution). Alaska has voted for only one Democrat in a presidential election since it first became a state, 60 years ago. Other red states run sovereign wealth funded by natural resources as well, though Texas puts its funds into education and Wyoming puts its funds into the general state budget.

When socialism and conservatism aligns

Many of these areas are frequently assumed to be unreachable for the American left. And yet, we continue to see conservative states and rural areas maintain policies and institutions that place wealth and enterprise directly in the hands of governments and communities. Even more so, we see that these policies both succeed and remain politically popular across the board. Indeed, the idea to mandate that large companies transfer partial stock ownership over to their workers, advocated for by Sen. Sanders and the left wing of the United Kingdom’s Labour Party, already has 50% support among Republicans.

What is happening here? Why does the right seem to viciously oppose socialism in rhetoric while simultaneously adoring the small slices of it that they have contact with?

Gar Alperovitz, who writes extensively on this topic, makes the point that socialist programs can in some ways align with conservative values better than traditional welfare state measures. Because public banks, public utilities, and sovereign wealth funds all can generate revenue on their own, they reduce the need for taxation. Because they’re run as independent organizations, they have also won support from conservatives as a way to discourage political meddling in public wealth: Former Republican Governor of Wyoming Stanley Hawthorne, when proposing his states’ sovereign wealth fund, argued that it prevents against the possibility that “some legislature at some specific time might get selfish and decide to spend all of that fund at one time.” Though this is a conservative rationale, it was used to justify a socialist strategy of public wealth ownership rather than a liberal strategy of taxation and legislative appropriation.

The case of Alaska suggests some limits to this idea, though. Polling in 1984, just two years after the Alaska Permanent Fund’s creation, found that only 29% of citizens would be willing to keep the fund if tax hikes were needed to keep it running. In 2017, 71% said they would be willing to pay higher taxes for the fund. Though not as scientific, an Alaskan news station also did a recent Facebook poll finding that, with over 10,000 respondents, 75% prefer a full dividend payout rather than directing the money to public services. As the program has become accepted as a part of life in Alaska, support for it has grown in such a way that it has wide approval even if it comes at the expense of lower taxes.

Part of this puzzle can be explained by the fact that the ideas described above are generally popular, but become controversial through being associated with party politics. In 2017, when free college existed only as a fringe proposal among progressives in the Democratic Party, one poll found that Republicans supported the idea 47% to 45%. But now that the idea has increasingly come into the spotlight as a proposal associated with the Democratic Party, polls find its support declining among Republicans, sometimes sharply. Researchers have found that someone who associates themselves with a political party is more likely to oppose an idea if it is framed as an idea from the other party. Kim Dancy, a researcher at the Institute for Higher Education, notes this effect in action in Tennessee: “The way they talk about free college in Tennessee is very different than the way they talk about free college on the Democratic side. It wasn’t as strongly associated with Democratic politics at that time. I would be very surprised if a Republican governor was able to do this today.”

Framing can have very powerful effects. Indeed, it seems likely that part of the reason credit unions and worker-owned businesses have received support from both right-wing voters and politicians is because they aren’t commonly understood through the frame of proto-socialist cooperative institutions, but instead are viewed as businesses, local community organizations, and participants in civil society—all things perfectly coherent with conservatism.

On the other hand, an additional explanation may be that public ownership allows for a sense of community pride. Perhaps the best example of this is the Green Bay Packers. The Packers is the only National Football League team in America which, rather than being owned by a couple of billionaires, is entirely owned by fans through a non-profit corporation. This has allowed the team to continuously remain a staple of the Green Bay, Wisconsin community even as other teams have moved around to chase population centers and tax benefits. As a result, the Packers have by far the most dedicated fan base of all 32 NFL teams while being located in the smallest metro area of any of them.

Public ownership—whether it be through state or local government, community, or a broad organization—gives everyone involved a direct stake in a collective project, generating support well beyond what seemingly distant federal government programs could. A similar effect is in play for such universal social programs as free college or Alaska’s universal dividend: When programs provide universal benefits rather than benefits targeted to just one segment of the population, support for them is much broader.

The final answer to this question is the simplest: people like these programs because they work. Whatever their original justification, these highly progressive approaches have all helped to deliver real, concrete gains to regular voters. Even many of the people with philosophical objections to public ownership or universal social programs have come around to support them when they see their actual results: accessible banking without Wall Street corruption, widespread educational opportunity, high-quality internet service, low electricity rates, or even just a check. Many Americans actually don’t actually have that strong of a coherent ideology and simply take cues on issues from sources they trust, so when a program has a direct and demonstrably positive effect on their life, they’ll generally just support it regardless of ideological convictions. “Conservative folks certainly have conservative identities that they hold dear,” Matt Bruenig has argued, “but that doesn’t mean they will endlessly oppose leftist programs. It just means they will endlessly oppose ‘leftist’ programs. If people really like a particular program (and who doesn’t like checks in the mail?), they’ll just rhetorically rationalize the program as being something more palatable to their nominally conservative political identities.” [Emphasis added.]

Lessons for advancing system change

As we have seen, leftist programs bordering on classical socialism can and have been successful in deeply conservative areas of the country. The idea that traditionally right-wing voters in the Midwest, South, or West will necessarily revolt against a Democratic Party moving to the left, or even against actual democratic socialist policies, is false. But these examples also provide important lessons.

The left must offer real proposals that deliver real progress on real issues. Anyone on the left seeking to reach out to areas often ignored by the progressives in recent decades should first and foremost stress how a genuine progressive agenda can directly improve peoples’ lives. Rural America is facing a devastating opioid crisis, deteriorating infrastructure, stagnant wages, and a secular economic decline at the hands of corporate-driven deindustrialization. Reaching segments of the population in these areas doesn’t have to mean abandoning progressive priorities on other topics, nor does it mean paternalistically talking down to them: it simply requires discussing ideas that give them hope and a chance to improve their lives.

These policies are not panaceas, either. Alaskan Republicans are attempting to use the Alaska Permanent Fund’s dividend as an excuse for deep cuts in other vital areas of public spending. Other institutions have environmental records in serious need of reform: the TVA’s energy generation is currently very dirty, and the Bank of North Dakota has provided financing for dirty energy projects like the Dakota Access Pipeline. Thus, even these public institutions should be strategically viewed not just independently of one another, but in a holistic fashion that takes all of their effects into account. Supporters should organize alongside local groups—like anti-poverty and good government groups resisting cuts in Alaska, or farmers and Native communities protesting environmental degradation in Tennessee. Indeed, supporters of institutions should look for ways to integrate these ideas with existing progressive projects, like using the TVA’s reach to implement low-cost rooftop solar, or having the Bank of North Dakota invest in wind energy and green social housing.

It may also be wise to begin thinking more locally in these areas. While many progressive priorities are clearly best handled on a federal level, these programs suggest that state and local government may be a way to build support for left-wing ideas by illustrating how change can be actualized in everyday life. With public trust in the federal government measured in the teens, creating smaller-scale institutions and policies that can support and build off of one another—what Alperovitz calls a “checkerboard strategy”—may hold great promise.

While even some rather liberal areas have had trouble accomplishing some of these policies, many red states already have real, living examples that we can point to about what a world that places people before profits might look like. Studying left-wing policy successes in otherwise conservative areas makes it clear that positive change can come from a bold progressive program.