Introduction

Climate change is an unprecedented global social, political, and economic crisis. Without drastic action, the United States will likely experience rising sea levels that will regularly flood major cities, more intense weather patterns that will destroy homes and businesses, longer and deeper droughts that will disrupt agricultural production, and an increase in disease that will put stress on the healthcare system. Domestic and international climate refugees will have to be resettled and the effects of increasing global strife contained. In both human and economic terms, the costs will be unlike anything the country has previously faced. Moreover, the economy is facing a significant problem of stranded assets—specifically fossil fuel reserves and infrastructure, the full value of which simply cannot be realized if the world is to avoid the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

In order to navigate these intersecting ecological and economic crises within the necessary (and shortening) time frames, we will likely need to take over and decommission the large fossil fuel extraction corporations that are both one of the leading causes of climate change and one of the primary institutional impediments to addressing it. On its face, this seems absurdly radical and improbable in the type of capitalist system that exists in the United States. However, the United States actually has a long and rich tradition of nationalizing private enterprise, especially during times of economic and social crisis. Importantly, this approach has often been deployed when private companies are hindering national efforts to address a crisis (either through obstruction, incompetence, or incapacity). This history of nationalization, along with other robust government economic interventions, suggests that far from being a non-starter, a public takeover of the fossil fuel industry should be considered an eminently plausible and viable policy option for dealing with the forthcoming climate crisis.

As does all countries around the world, the United States government regularly plays a variety of active roles in the functioning of the economy, including direct interventions on behalf of certain firms and sectors. For instance, the fossil fuel industry itself receives around $26 billion a year in government subsidies. The government also routinely provides financial assistance to strategically important companies that are experiencing financial difficulties. What makes these types of more regular economic interventions different from nationalization is the question of ownership and control. Nationalization is the process of bringing previously privately controlled assets (businesses, land, real estate, services, natural resources, etc.) under public authority. While a shift in control is often associated with a transfer of ownership, as will be documented in this paper, this is not always the case. In some instances, the government has taken legal and operational control of an enterprise or asset without taking an official ownership position. This results in some blurred lines when it comes to determining when a government intervention does and does not amount to nationalization. In what follows, I have attempted to only include examples where there is a clear shift in either ownership or control (or both).

I have also endeavored to only include examples of nationalizations at the federal government level. This is because, perhaps paradoxically, government seizure of private assets at the state and local is ubiquitous in American history and contemporary experience. Through the process of eminent domain, state and local governments take over private land and other assets for a variety of purposes every day. For instance, recently it was announced that the city government in Washington D.C. plans to acquire (and then knock down) a Wendy’s fast food restaurant in order to conduct some much-needed traffic improvements. It would be simply impossible to document the millions (if not tens of millions) of instances of public takeover of private property in American history. Lastly, what follows is intended to be merely an illustrative history of nationalization in the US with a focus on the mechanisms and processes by which it was effectuated.

While I do not pretend that I am not generally sympathetic to public ownership, by and large this paper attempts to avoid judgements on the merits for or against nationalization in each case, or its successes or failures.

Read and download

Video: A (brief) history of Nationalization in the US

Jacobin: “Nationalization Is as American as Apple Pie”

In Jacobin, Thomas M. Hanna writes, “Today, we are facing intensifying ecological, social, and political crises: the steady erosion of workers’ rights, pervasive racial injustice, ballooning inequality, ever-rising health care costs, growing disillusionment with democracy, and catastrophic climate change, to name but a few. It is critical we use every policy tool at our disposal. And while nationalization is certainly no panacea, and not universally applicable, it should be destigmatized and seriously considered as the solution to a variety of social ills.”

Read the full article in Jacobin.

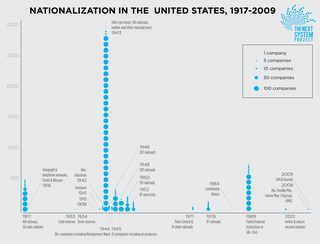

Interactive timeline: Nationalization in US history

Infographic: Frequency of nationalizations in US history