California’s large investor-owned utility, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), announced it would be filing for bankruptcy by the end of January after being faced with $30 billion in damages related to a series of fires over the past two years, including last fall’s deadly Camp Fire, which was allegedly sparked by the utility’s old, faulty transmission lines.

That fire killed 86 people, destroyed 14,000 homes in the town of Paradise, and stands as the deadliest and most destructive fire in the state’s history.

PG&E’s bankruptcy forces a critical choice for new California Gov. Gavin Newsom and other state leaders. They could opt to bail out PG&E or break up the gargantuan company into presumably more manageable pieces.

Or they could do the right thing and take the utility into democratic, public ownership.

A public takeover is not outlandish, but rather, is a common-sense proposal for the future of Californians. With the company’s value dropping precipitously, this is a key moment for the state to step in, take over, and design a utility system that centers affordability, reliability, resiliency and leadership on climate change. Public ownership could also help secure the priorities that bankruptcy puts up in the air — such as pensions, union contracts and renewable energy investments — that the for-profit utility might not value saving as much as it would CEO bonuses.

The idea of public ownership is getting traction. California communities are tired of dealing with the consequences of a company designed to deliver maximum shareholder returns, constant growth and big-dollar CEO paychecks rather than safe, affordable power that does not put people and the planet at risk.

As an Oakland attorney of a group suing PG&E describes, “Rather than spend the money it obtains from customers for infrastructure maintenance and safety, PG&E funnels this funding to boost its own corporate profits and compensation.” The utility has been under scrutiny for its safety culture for years, including a gas explosion in 2010 that killed eight people.

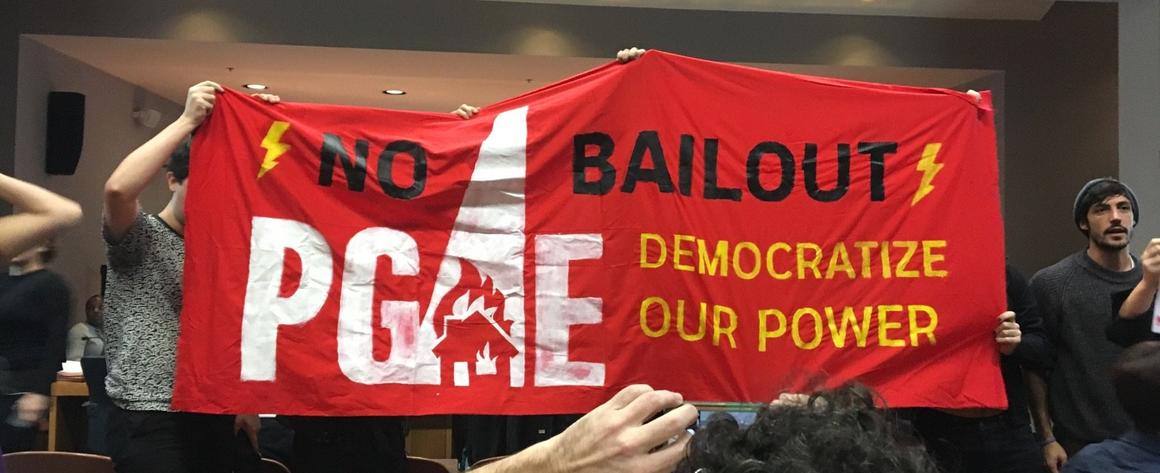

In November, protesters shut down a California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) meeting, calling for a public takeover of the company and to reject a bailout that puts the brunt on ratepayers (for which PG&E has lobbied hard). After the protesters were escorted out, CPUC President Michael Picker said that the commission is investigating the company, leaving all options on the table — be it bailout, break up or even public takeover. In the investigation, CPUC even names the option: “Should some or all of PG&E be reconstituted as a publicly owned utility or utilities[?]”

State Senator Scott Wiener from San Francisco announced a proposal for San Francisco energy municipalization in reaction to the bankruptcy news. “As disruptive as it is, PG&E’s bankruptcy creates an opportunity to form a comprehensive publicly owned electric utility in San Francisco,” he said. State Senator Jerry Hill, an outspoken critic of PG&E, has championed a call to hold PG&E accountable for its actions and is now also considering a public takeover option.

California already has a flourishing form of quasi-public power ownership, called Community Choice Aggregation (CCA). This program allows local governments to pool electricity customers from their jurisdiction and take over the procurement of energy generation for their communities. There are already 19 CCAs operating in California, serving a total of 2.6 million customers. Advocates for CCAs argue that they allow their communities to transition to 100 percent renewable energy more quickly, enable more community control and charge lower rates.

So how could a state-owned utility work?

California could take over PG&E and build a fully reimagined energy utility system based on 21st-century grid realities and community needs, with any money made reinvested back into the grid or the larger community rather than shelled out to shareholders. State-owned regional grid operators could manage the energy delivery throughout different regions of California, focused on keeping the grid safe, investing in modernization and accelerating the electrification of new sectors of the economy, such as transportation.

Local government CCAs could take on building or procuring energy generation, prioritizing locally owned renewables and so-called “non-wires” alternatives to create a more climate-resilient energy system, such as solar panels and battery storage, that doesn’t require the kind of transmission lines implicated in the Camp Fire and other large fires. The CCA could also take on reducing energy burdens — particularly for low-income residents who are often people of color — by integrating plans for energy efficiency with local plans for affordable housing.

East Bay Community Energy’s CCA serves as a clear example of how public ownership can be democratically governed and its benefits distributed, as well as a testament to the power of grassroots organizing by Local Clean Energy Alliance to keep the CCA centered on climate justice. For example, the CCA adopted a local development business plan to promote local renewable energy projects and jobs. It is also democratically run, with a board of directors consisting of accountable elected officials from the different jurisdictions, and monitored by a community advisory committee of rotating community stakeholders.

Utilities across the US are faced with a business model that is insufficient for the challenges of the 21st century and for delivering a public good. Taking over PG&E is not just crisis control; it is a pathway to a more democratic energy system that values local workforces, spreads the wealth and accelerates the energy transition.