Following is a complete archive of the materials produced for the 2016 Next System Teach-Ins as well as highlights from some of the dozens of teach-ins that took place, from New York to California. While we are updating some of the teach-in materials and working to provide new popular education materials, we’re making all of the materials from past teach-ins available for your use including videos, curricula and facilitation guides. If you organize a teach-in at your school or in your community, or if you use any of the materials below in a class or workshop, we’d love to hear about it! To get in touch with us, please send us an email.

Table of Contents

Our Vision: Expanding the Teach-Ins Tradition

Are you tired of business as usual? Want to help millions of Americans learn about the real alternatives that already exist and how to be a part of them?

We know the current system does exactly what it was designed to do: line corporate pockets at the expense of real people’s health and livelihoods, destroying the environment and fueling the war machine at the same time. But we also know that another world is possible. Many models for more economically and ecologically sustainable societies exist and as the ills of the current system become more apparent to the country at large, people are hungry to know what viable alternatives exist. The Next System Teach-Ins aim to help communities and campuses across the country engage in that debate and start exploring the alternatives that work best for them.

The teach-ins can be a powerful component to a growing national debate about what this country really needs and how we get there. In a time of political stalemate, we have to take responsibility for the important conversations and build the community needed to transform this country.

Host a teach-in at your school or attend one near you to find out more. We’ll provide sample curricula, agendas and workshop ideas based on existing alternatives, burgeoning initiatives and cutting edge research in order to help you create an engaging and effective teach-in that brings your community’s work to the next level.

50 Years: The Roots of the Next Major Teach-In Wave

By Ben Manski for The Next System Project. December, 2015

Over each of the past five decades, those seeking an expanded and intensified political debate have organized waves of coordinated events they have called “teach-ins.” Beginning in the mid 1960s with the teach-ins on the war in Vietnam and continuing on through the 1970s and 1980s with the use of teach-ins by the environmental, women’s, anti-Apartheid, and anti-nuclear movements, into the 1990s and 2000s with the Democracy Teach-Ins and Tent State Universities, and most recently with Occupy and Black Lives Matter, activists have periodically revived the tradition of campus teach-ins.

Teach-ins transform college and university campuses into political fora in which students, faculty, and community members take collective responsibility for matters of community, national, and global import. They usually involve large scale gatherings combined with smaller, more intensive workshops. One thing that makes a teach-in different from a conference or an academic seminar is the teach-in’s focus on producing knowledge for use by participants as members of an organized, politicized campus community. Another is the use of a “wall-to-wall” organizing approach in which every member of the community is challenged to engage in discussion and debate on the question at hand. The major waves of teach-ins of the past 50 years have gone beyond the choir to inspire large numbers of people to expand their sense of the necessary and the possible.

In the early months of 1965, what was to become a wave of teach-ins on the Vietnam War began at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, spreading eventually to 120 campuses in 35 states. This first teach-in wave was inspired by the use of the sit-in tactic in the civil rights organizing of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). At Michigan, over 200 faculty and 3000 students participated in what psychology professor Anatol Rapaport called an effort to, “establish a counterforce to the engineering of consent.” That counterforce emerged rapidly out of the teach-in process, greatly expanding the reach of the anti-war movement and deepening the questioning of long-held assumptions about the the role of the United States in the world system. As social historian Staughton Lynd said at the teach-in at UC Berkeley, by the end of the Spring 1965 college term it was clear that, “if you are worried that the natives all over the world are restless, we want you to know that the natives here at home are restless too… .”

The restlessness Lynd spoke of meant that this first teach-in wave quickly transitioned to more confrontational direct action organizing against the Vietnam War, and as a result, the next major wave of teach-ins focused on a different subject and did not take place until 1970. Proposing the first Earth Day as a “national teach-in on the environment,” Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson teamed up with organizers based in Santa Barbara, California to mobilize 20 million people for teach-ins, festivals, and marches. This revival of the mass teach-in as a movement-building tool was soon carried forward throughout the 1970s and 1980s in other social movements, including the women’s movement, the anti-nuclear movement, and the out-of-apartheid in South Africamovement. In the 1970s, some of these teach-ins were quite large and numerous ﹘ with 151 campuses taking part in anti-nuke teach-ins in 1981, for example ﹘ but by the later 1980s the size and number of teach-ins was significantly reduced, reflective of the more limited capacity of progressive social movements at that time. Alongside this reduction in scale came a more generalized and amorphous use of the word “teach-in” to apply to all kinds of educational events, regardless of scale, participation, or purpose.

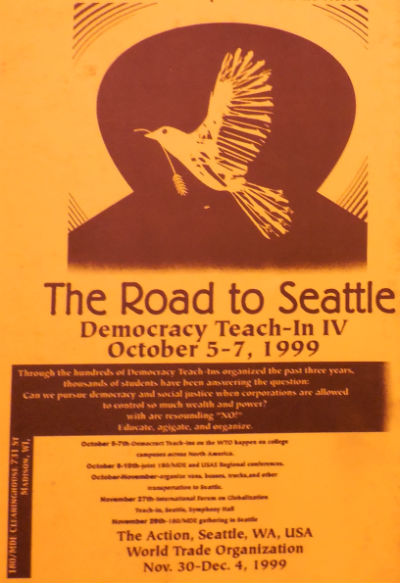

This began to change with the next major waves of college teach-ins, which took place in five rounds beginning in 1996, under the slogan, “Teachers are not tools, students are not products, the university is not a factory!” These “Democracy Teach-Ins” took on the corporatization of the university and society, reviving the mass organizing approach and structural critique of the late 1960s and early 1970s by asking students on over 400 campuses the question, “Can we pursue democracy and social justice when corporations are allowed to control so much power and wealth?” The first rounds of the Democracy Teach-Ins built the networks and analysis through which the student anti-sweatshop movement emerged and they played a critical role in educating and mobilizing students for the mass protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle in late 1999. Later rounds of the Democracy Teach-Ins gave rise to the pro-democracy campus organization 180/Movement for Democracy and Education (180/MDE), which, together with the Students Transforming and Resisting Corporations (STARC) organized further teach-ins and actions leading up to the Books Not Bombs! student strike of 2003, which mobilized mass walkouts on college campuses around the world.

Immediately following the Books Not Bombs! strike, students and faculty at Rutgers University organized an outdoor encampment they called “Tent State University,” modeled on the popular universities and teach-ins of the 1960s and 1970s and prefiguring in many respects the Occupy Wall Street process of 2011-2012. The Rutgers organizers joined in the following years with the Democratizing Education Network, which in turn helped to nationalize Tent State University to campuses in other regions of the United States and eventually to other countries.

More recent use of coordinated teach-ins on a mass scale took place first with the Wisconsin Uprising of 2011, in which sociologist Frances Fox-Piven of the City University of New York led efforts to nationalize that uprising through national teach-ins held on April 5th, the national student labor day of action. Occupy Wall Street and the Occupy movement soon followed, making extensive use of teach-ins on hundreds of college campuses and community spaces, as well as at Occupy encampments throughout the Autumn of 2011 and into 2012. In keeping with Occupy’s culture, these teach-ins were often distinguished from earlier waves of teach-ins in that they were more participatory and open in their formats and subject matter.

Most recently, beginning in 2013 with the Ferguson Uprising, the Black Lives Matter movement has organized college teach-ins to, “help bring the national movement into the community and onto local campuses,” and to, “inform, inspire and mobilize people to combat racism and racially motivated violence, and generate a sense of solidarity that can lead to future activism for social change.” Those teach-ins, in turn, are credited by some with helping to prepare the way for last month’s National Blackout and Student Blackout actions, alongside the mass protests at the University of Missouri against racism on campus.

On December 8th of 2015, a coalition of several dozen national and statewide student, faculty, labor, and community organizations issued a call for a first wave of Next System Teach-Ins, scheduled for the Spring of 2016. What social change will these teach-ins bring?

Inaugural Teach-Ins unite students, activists, and visionaries from New York to Madison

By Michelle Stearn for The Next System Project, March 22, 2016

The beginning of March brought a wave of connections and developments for students, community activists, economists, and visionaries of all kinds at the Next System Project Inaugural Teach-Ins. What in the world is a “teach-in,” you might ask? The word hearkens back to the nonviolent direct actions that took place at universities in the ‘60s to organize and educate against the Vietnam War, and have taken a myriad of radical shapes and forms throughout history. The Next System Teach-Ins are taking the “Teach-In Tradition” to new heights by cultivating platforms for people of all disciplines and communities to come together to envision what the next political-economic system might look like in our society, and how we can build towards that system collaboratively, starting in our own communities.

The energy was certainly swelling from the moment The Next System Project launched the teach-ins in December 2015. Hundreds of people registered to get involved from Detroit, MI to Seattle, WA to Tuscan, AZ and beyond. And now, our inaugural teach-ins have given a whole lot of life to the growing calls for changing the whole system.

Questions and visions about intersectionality and unity buzzed through the windows and doors where the workshops were going on, from New York to Madison, WI at the inaugural teach-ins. What does participatory budgeting at the municipal level have to do with workplace democracy? How can the technology sector provide the tools to democratize knowledge, power, and wealth? What are ways we can shape our institutions – governmental and otherwise – to guarantee a system that espouses racial and gender equality? How can students change the structure of their colleges and universities to fight against exploitation of low-wage agricultural workers? Participants and presenters at the inaugural teach-ins delved into these questions and so many more at our inaugural teach-ins.

In Madison, a student panel kicked off the two weeks of inaugural events with a powerful message about the need for interconnectedness and unity across all movements for change. Danny Levandoski, a Student Labor Action Coalition member and one of the students on the panel, highlighted his experiences that fueled him to work to change the status quo on transgender and transsexual discrimination. Danny situated his struggle within a larger systemic arena: “Once we start drastically altering the economic and political system, then we’ll see true change.”

The sentiment among the students was one of urgency, as the depth of the problems society faces only seems to be trumped by the power students and activists ignite in the fight for systemic change. Kaja Rebane, a graduate student and climate activist who also served on the panel, remarked, “Like the climate system, human social systems don’t change gradually, and that can be a good thing!” Her confidence in the power of students and communities to make those grand systemic shifts reflects the resounding ideals and determination of the Teach-Ins community: together, communities are already building the future.

-Deepak Kumar, a participant from New Jersey, reflects on the The Next System Project NYC Convening

Fast forward one week to the opening plenary at the New York City Convening (a.k.a. The New York Inaugural Teach-In), where a similar sentiment of people power had a packed auditorium at The New School a-buzz about alternatives to the current system. “When the system collapses, we must have tangible alternatives already in place,” said Autumn Marie, a Black Lives Matter activist who spoke on the plenary amongst distinguished speakers such as CUNY Graduate Center’s Frances Fox Piven and Fund for Democratic Community’s Ed Whitfield. Autumn went on to call for a unified paradigm shift: that “capitalism should actually be seen as the alternative to the next system we are creating.” The conversation at The New School delved into a multitude of these necessary paradigm shifts – from the de-commodification of housing to the notion that public banks can serve as a building block for an economy oriented towards human well-being – setting the stage for two full days of workshops held at the Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies.

At the opening events of both the Madison and New York City Teach-ins, it was clear that the events were providing a much-needed platform for people to unite and share ideas and strategies for shaping the next system. What followed the opening nights were two jam-packed weekends, filled to the brim with workshops, debates, panels, interactive plenaries, and most of all, collaborations and connections amongst what might have otherwise been disparate groups. In Madison, for example, activists from the Young, Gifted, and Black Coalition were able to share strategies and visions with organizers from the 350.org fossil fuel divestment campaign. Ed Whitfield, co-founder of the Fund For Democratic Communities, put it succinctly in a New York workshop entitled What’s After Divestment? Investing in a Just Transition: “We must re-integrate our life and community so that our economic life matches up matches up with our needs as humans – and that’s what this work altogether is about.”

The conversation in New York City continued from sunup to sundown, as our friend Laura Flanders of The Laura Flanders Show hosted WBAI’s Morning Show on FM Radio, with a focus on new systems and practices for a more inclusive future. Laura invited visionaries Aaron Bartley and John Washington of People United for Sustainable Housing (P.U.S.H.),” plus Sarah Leonard (senior editor of The Nation) and Bhaskar Sunkara, (Founding editor of Jacobin Magazine) co-authors of “The Future We Want, Radical Ideas for the New Century,” and finally, in order to highlight the Inaugural Next System Teach-In: Dana Brown (National Teach-Ins Coordinator) and Gar Alperovitz (author of What Then Must We Do? America Beyond Capitalism and Next System Project co-chair). Laura also attended the Teach-In later that day, as one of her guests on the radio show Piper Anderson led a workshop called The Mass Story Campaign: A Public Reckoning with the Impact of Mass Incarceration.

In NYC, Brooklyn-based Octavia Project guided workshop participants to envision the next system using cognitive techniques like free science fiction writing and map-making.

As the Next System Project National Teach-Ins Coordinator Dana Brown observed, “People traveled from around the state and also from nearby states to participate in the Madison teach-in, and their response was resounding: we need more events like this! Educators, students and community alike made it very clear to us that they are committed to system change and to bringing this conversation to communities across the region.” Other presenters and participants agreed.

There’s such a need to drive this different thinking and paradigm shift. For us, it really becomes imperative to open up access and space to allow people to define their place of value within this Next System and this new ecosystem of social change.

-April De Simone of Designing the We, during a workshop at the NYC Convening she co-led called Building the Voice and Power of Business for a Sustainable Economy

Students at University of Wisconsin-Madison watch the closing ceremony of their teach-in after a weekend of workshops, discussions, and debates about the Next System. (Photo: Michelle Stearn)

So, what’s next for the teach-in movement? These inaugural teach-ins were just the start of a nationwide wave of community-led teach-ins from Detroit, Michigan to Santa Barbara, California. “I can’t keep up with the requests for more information, ideas for follow-up and individuals who want to host teach-ins at their school or in their community,” said Dana, who as the National Teach-Ins Coordinator, reaches out on an individual basis to those who are interested in hosting their own events and have heard about the Teach-In model. The inaugural teach-ins this month also added fuel to the fire, inspiring students to take the Teach-In idea back to their communities and schools. Deepak, a college student from New Jersey who traveled to New York City for the weekend to attend the event, told us:

“Every session has been a spark for me… I’m always thinking in my head, what are ways we make things better, and how can we change systems? Coming here, and hearing about what people are actually doing, my head is spinning! We learned about community land trusts, worker cooperatives, alternative currencies, decentralized forms of organizing – all these radical ideas. So I’m just letting my imagination run wild thinking about all the future possibilities.”

See more photos on our Flickr:

Check out our social media storm around the NYC Convening at #WhatsNextNYC:

Resources and Literature

FAQ

What kind of support can I expect from you in organizing my teach-in?

The Next System Project will provide:

- a full curriculum and modular pieces of curriculum to be used as each group desires including articles, videos and discussion guides, and more

- one-page summaries of various system models for download and use

- templates for flyers, publicity items and evaluations

- a list of potential speakers if universities would like to invite outside speakers

- sample RFPs for those that want to solicit workshops from the community

- the website infrastructure to receive RSVPs, post agendas and interact with participants (which we can link to Facebook events if you’d like)

- taped greetings from a couple of high profile NSP supporters addressing teach-in participants around the country

- a closed Facebook group for all local teach-in hosts that want to share ideas or ask one another questions

- staff support for questions, requests for new materials, etc

- we will publicize your teach-in and help attract participants

Why just college campuses? What about community teach-ins?

Don’t let us limit you! If you’d like to host a teach-in at a community center, place of worship, union hall or park, we’d love to hear about it and will support you as much as possible. We’re encouraging students, staff and faculty to host teach-ins on campuses because we believe the university should serve the public good and should be a place where deep and broad debate on pressing issues can occur—and that doesn’t seem to be the case with many US universities at the moment. However, that doesn’t mean our communities shouldn’t also host these conversations. We’re a small operation and chose to start on college campuses.

Do you have funding for these teach-ins to help us bring great speakers and resources to our campus/community?

Unfortunately we do not. We are a small operation and that’s why we’re focusing on producing and pulling together the best materials possible and making those available to you. We’re also happy to provide advice and help you find ways to fund your teach-in activities through co-sponsorships on your campus or in your community. We also offer several low-budget ideas (film and Q&A, student-run workshops, etc).

Where do I download the teach-in packet?

We have decided not to produce a one-size-fits-all packet for the teach-ins because we think different materials and approaches make sense in different places according to resources available, but also the interest and focus of the students and staff. However, make sure you check out the Teach-Ins Toolkit and Guides below where we have information for facilitators, sample workshops, documentary films to screen and more.

What should the outcome of our teach-in be?

We propose two primary goals for the teach-ins: Nationally, we’d like the teach-ins to serve as a first step towards engaging people in discussion and debate about alternative political-economic models. Locally, we’re encouraging each teach-in host to come up with a further local goal or two (for instance, there might be a pressing issue on campus that you want to build a campaign around, or perhaps you’d like to start a discussion group. Maybe you’d want to ask the Economics Department to include alternative models into a course or help create a new initiative in your community that follows one of the system change models you discussed at your teach-in…there are many possibilities and we’re happy to talk through them with you).

After the teach-ins, we will provide a forum for hosts and participants to share their experiences and ideas for next steps as well as upload and share video or audio of panels, keynote speakers, debates or workshops so we can begin to create a repository of Next System materials that can help people all over the nation start this discussion

How do I find other people in my community/campus that might want to help organize or attend a teach-in?

Once you’re registered to host a teach-in, we will set you up with a page on the website and we can direct anyone in your geographical area to your teach-in page. We’ll encourage them to RSVP for your teach-in and/or volunteer their time to help you pull your event together. You can also create a Facebook event, and if you let us know, we can link the two event pages so you don’t get duplicate RSVPs.

Teach-In Curriculum

Facilitator’s Guide

System Change Guide

David Schweickart Reading Guide

Read David Schweickart’s essay. Economic Democracy

Jessica Gordon Nembhard Reading Guide

Read Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s essay, Building a Cooperative Solidarity Commonwealth

Marvin Brown Reading Guide

Read Marvin Brown’s essay, A Civic Economy of Provisions

David Bollier Reading Guide

Read David Bollier’s essay, Communing as a Transformative Social Paradigm

Hans Baer Reading Guide

Read Hans Baer’s essay, Toward Democratic Eco-Socialism as the Next World System

Riane Eisler Reading Guide

Read Riane Eisler’s essay, Whole Systems Change

Robin Hahnel Reading Guide

Read Rabin Hahnel’s essay, Participatory Economics and The Next System

Lane Kenworthy Reading Guide

Read Lane Kenworthy’s essay, Social Democracy

The Pluralist Commonwealth Reading Guide

Learn more about Gar Alperovitz’s vision for a Pluralist Commonwealth

System Change: Key Principles

Case Study: Murray Bookchin, Communalism, and Rojava

Read Thomas Hanna’s essay, Kurdish Women Struggle for a Next System in Rojava

Indigenous Declaration Facilitation Tool

Teach-In Toolkit

Climate, Energy, and Environment: System Change, Not Climate Change!

Climate change is one of the central challenges of the twenty-first century. While many have begun to make worthwhile and important changes in their personal consumption habits, solving the problem at scale will require tackling the underlying power relations that are blocking overall solutions. Adoption and implementation of certain principles will be needed to move to a next energy system that actually sustains and restores the natural world, including the climate regime that has existed throughout human history.

We must envision the economy as nested in and dependent on the world of nature, its resources, and its systems of life. We must recognize the rights of species other than humans and nature generally and otherwise transcend anthropocentrism. We must recognize that environmental success depends on correcting the underlying drivers of environmental decline and working for deep, systemic change outside the current framework of environmental law and policy. We must respond to climate change – and associated global-scale challenges like food security – through far-reaching and innovative approaches.

>Urgent action must be taken within the context of the current system, but we also need to promote deep change in that system. We will never go far enough and fast enough as long as the effective priorities are ramping up GDP, growing corporate profits, increasing the incomes of the already well-to-do, neglecting the half of the population that is barely getting by, consuming endlessly, focusing only on the present moment, helping abroad only modestly, and other dominant features of our current system. As climate demonstrators have urged, what is needed is “system change, not climate change.” The climate actions that are now urgently needed must have the effect of driving a vast transformation of energy production to renewable energy.

Essentially all US power production will need to be from renewables by 2050. So the question is: will the ownership and control of the vast new investment and the new facilities be by the same entities and done in the same ways as always? Or will this new renewables sector set the model for industrial and manufacturing development in the next system, with the goal of decentralized, locally-financed, -owned and -operated power production?

Some great resources to help you put on workshops in this area

- Movement Generation’s Body Earth workshop

- Toward a Climate Justice Energy Platform: Democratizing Our Energy Future, December 2015

Lays out a vision, political framework, strategies, and principles of democratized energy development as the basis for a proposed platform to advance energy democracy in the U.S. Includes model policies and programs and snapshots of climate justice energy advocacy from around the country.

Equity and Justice for Oppressed Communities

It is abundantly clear to many oppressed communities that we face a systemic crisis not only in connection with the economy, but in connection to the institutionalized racism and discrimination ingrained in every aspect of our society. With a judicial process built to serve and protect a small elite, rampant violence against people of color, immigrants, women and LGBTI communities and persistent economic exclusion from the wage gap to redlining, the inequality and prejudice inherent in the system are painfully clear.

The facts tell a grim story—one that needs to change. Currently, African American and Hispanic American men are incarcerated at staggeringly higher rates than whites. Violence against women is endemic and institutionalized with a woman assaulted every 9 seconds and a full 20 percent of women raped during their lifetime. Transgender women, especially trans women of color, are being murdered at a rate so high that some have called it a state of emergency for the transgender community. Native Americans are the victims in 1.9 percent of police shootings, despite making up just .8 percent of the population—a rate higher than any other ethnic group. Growing Islamophobia has fueled hate crimes, attacks on freedom of religion, harassment and profiling. And despite well-publicized advances, LGBTI people and immigrants continue to face varying degrees of legal, political, and cultural persecution.

These realities stem from an ongoing history of white supremacist and patriarchal power structures that have been reinforced in reaction to the economic and political demands of those oppressed by the system. Vibrant and visionary struggles of oppressed communities throughout American history have, for the most part, been met with a paralyzing mix of repression and inadequate reform.

Any truly transformative next system will have to address the persistent structural barriers to equity and opportunity faced by oppressed communities and figure out how to move way beyond formal inclusion in political and civil life to real equality and opportunity.

There are alternatives, both in theory and practice. The “alternative traditions” of African American and immigrant communities based on cooperation, mutualism, and self-help, have been well-documented. Their lineage can be traced to African mutual aid societies, Hawala and trueque networks, through to today’s efforts by groups like the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement working to rebuild the economy of Jackson, Mississippi.

Furthermore, communities across the United States are experimenting with and advocating for community control of police, alternative sentencing and restorative justice policies that significantly shift the balance of power in the application of law and order.

Such traditions, born of the necessity of finding strategies aimed at delivering independence, solidarity, and community self-preservation, offer models and inspiration for alternative developmental paths that rooted in long histories of political struggle and the everyday experiences of ordinary people grappling with systemic problems.

Some resources to help you put on workshops or activities in this area:

- Policy Link and the Center for Popular Democracy’s Building Momentum from the Ground Up: A Toolkit for Promoting Justice in Policing

- The Catalyst Project’s Catalyzing Liberation Toolkit: Anti-Racist Organizing to Build the 99% Movement

- An oldy-but-goody, Critical Resistance’s Prison Abolitionist’s Toolkit

From Economic Crisis to Economic Democracy

The economy is stagnating. Communities are in decay. The lives of millions are compromised by economic and social pain. For decades now, virtually all the gains to the economy have been captured by the very rich, while the vast majority have received a declining share of increasing productivity. For more than forty years there has been virtually no change in the percentage of Americans living in poverty—if anything, there is evidence of a worsening trend.

Student debt is exploding, now surpassing a trillion dollars, mortgaging the prospects of future generations. Traditional strategies to achieve equitable economic outcomes simply no longer work. The government no longer has much capacity to use progressive taxation to achieve equity goals or to regulate corporations effectively. Corporate power dominates decision-making through lobbying, uncontrolled political contributions, and political advertising. Union density, historically an important measure of countervailing power, has fallen from a post-war high of 34.7 percent in 1954 to just 11.1 percent in 2014—and a mere 6.6 percent in the private sector.

The good news is that the inability of traditional politics and policies to address fundamental challenges has fueled an extraordinary amount of experimentation in communities across the United States and around the world. It has also generated increasing numbers of sophisticated and thoughtful proposals that build from the bottom and begin to suggest new economic possibilities beyond the failed systems of past and present. Unbeknownst to many, literally thousands of on-the-ground efforts have been developing. These include cooperatives, worker-owned companies, neighborhood corporations, and many little known municipal, state, and regional efforts. Even experts working on such matters rarely appreciate the sheer range of activity. Practical and policy foundations have been established that offer a solid basis for future expansion. A body of hard-won expertise is now available in each area, along with support organizations, and technical and other experts who have accumulated a great deal of direct problem-solving knowledge.

Thus we encounter the the caring economy, the provisioning economy, the restorative economy, the regenerative economy, the sustaining economy, the collaborative economy, the participatory economy, the solidarity economy, the gift economy, the resilient economy, the steady state economy, the new economy, and many, many more. There are calls for a Great Transition, or for a reclamation of the Commons. Although precisely what “changing the system” means is obviously a matter of debate, certain key points are clear. The new movements seek a cooperative, caring and community-nurturing economy that is ecologically sustainable, equitable, and socially responsible — one that is based on rethinking and democratizing the nature of ownership at every level and, along with this, challenging the growth paradigm that is the underlying assumption of all conventional policies. In short, these movements seek an economy that gives true priority to people, place, and planet. Such an economy, so different from our own, requires a radical redefinition of terms beyond a narrow choice between “capitalism” and “socialism.”

Some resources to help you put on workshops or activities in this area

- The MIT CoLab and the Bronx Cooperative Development Initiative’s Economic Democracy Training Series

- Movement Generation and People Organized to Demand Environmental and Economic Rights’ half-day workshop Building Economy for People and Planet

More Online Resources

Formats for discussion and engagement: You can engage your campus in conversation about system change and next system models in any of a number of different ways—get creative! Here are just a few ideas to get you started:

- Ask student groups, faculty members and community groups to put on workshops or give talks on a variety of issues related to the system change you’d like to see. Issue areas could be: education, economic democracy, justice systems, law, local governance, finance/credit/currencies, ecology and climate, and more!

- Host a debate between two or more individuals or groups with different opinions about the type of system we need

- Get an improv troupe to play improv games with your group that help you imagine what the components of a new system would look like

- Play system change games like those laid out in: The Systems Thinking Playbook

- Map out the institutions and biases of the current political-economic system with your group, then spend time discussing and mapping the institutions and biases of the system you’d prefer to live in (See examples like the US Solidarity Economy Network’s map tool)

Workshop and facilitation ideas: A few fun ideas for how to run a successful workshop and different methods for engaging people in discussion and debate

- How to hold an Open Space meeting/conference: Open Space is a technique for holding meetings or events focused around a particular topic or purpose, but which begin without a formal agenda. For more ideas on how to hold an Open Space type teach-in see: http://openspaceworld.org/wp2/

- World Café tools for facilitating dialogue in large groups: Events hosted using the World Café process are broken into multiple short discussion sessions. During each session, participants meet around tables in small groups to discuss a question posed at the beginning of that round, and then move to a new table with different people before the next round of discussions. At the end of the meeting, insights from the many discussions are shared with the entire group. For more, see: http://www.theworldcafe.com/overview.html which includes a free toolkit you can download to help you host an event of this style: http://www.theworldcafe.com/tools-store/hosting-tool-kit/

- Graphic Facilitation: Graphic facilitation is the process of translating complex concepts into a visual language of words and pictures and recording them in real time. This strategy can be a very effective way to summarize and communicate complex ideas and to allow participants to see and internalize the big picture of a discussion or presentation. For more ideas about how to incorporate graphic facilitation techinques into your teach-in, see: http://graphicfacilitation.blogs.com/

- Tips for facilitators: check out the great tips from our friends at 350.org. Andthese games, warm-ups and energizers.

Systems thinking resources: Want to change the system? It helps to know how systems work and understand their functioning before designing a model for change. Here are some places to start:

- Linda Booth Sweeny’s work: which includes a great list of resources for teaching, learning and working with systems:

- Free introductory readings/courses on systems thinking: https://www.leveragenetworks.com/learn#systems-thinking

Further Inspiration

- Beautiful Solutions: “the most promising and contagious strategies for building a more just, democratic and resilient world”

- Yes! Magazine: Powerful Ideas/Practical Actions

- The Eco Tipping Points Project: Models for Success in a Time of Crisis

- System Dynamics Society

- Systems Thinking World

Draft Agendas

Here are some sample agendas for different length teach-ins. There are many more possibilities for how to organize your teach-in, and already people around the country have taken the Next System inspiration to organize all sorts of great events. Some include music and theater, others include thesis presentations of economics students studying alternative economic models. Organize the teach-in that makes sense for your campus/community. If you’re interested in hosting a teach-in, we’re happy to connect you with the other hosts to share even more ideas and materials.

Generic Teach-In Request for Proposals

1-page Guide for Teach-In Hosts: How to hold a Next System Teach-In

1. Decide on a format for your teach-in: Your teach-in should meet the needs of your campus. While one teach-in might be a 3-day event full of workshops and plenary sessions, another could be a simple film screening and discussion, a debate, or a single workshop. Do what makes sense on your campus and what you know will be engaging to your audience! We’ll provide plenty of materials to choose from: sample curriculum, workshop ideas, a documentary film you can bring to your campus and more.

2. Reserve a space: Talk to central booking on your campus and/or community centers, places of worship or local unions. Don’t wait until the last minute because you might have to fill out forms in advance and wait for approval to make your reservation.

3. Publicize your teach-in: how will you publicize your teach-in? You might wantflyers/quarter cards, a Facebook page, announcement bulletins, sidewalk chalk, plugs on campus radio, post your event on the student activities calendar or in a local paper, make announcements at meetings of relevant groups and more!

4. AV equipment needs: What do presenters and facilitators need? A projector? Sound system? Do they come with the room(s) you reserved? Do you have someone who knows how to operate all the equipment?

5. Registration: How do you want people sign up for the teach-in and get any materials they need like an agenda? How do volunteers sign up to help you out? Sign up now to have a page on our website to centralize all that! Just click here.

6. Materials: What materials do you need for the teach-in itself? Likely you’ll need things like markers, white boards or flip charts, tape, scissors, sticky notes, sign-in sheets, nametags, you might also want to offer refreshments if your teach-in is a full day or more.

7. Speakers/Presenters: You might want to ask local professors or organizers to present on a panel, engage in a structured debate, or facilitate a workshop as part of your teach-in. Remember to contact them early on to make sure your top choices are available. If you’d like to bring outside speakers to your university, there are plenty of great choices and you might be able to fund their trip through student activities and/or departmental co-sponsorships. If a speaker can’t make the trip, consider asking them to present over Google Hangouts, do a webinar, or even pre-tape a message for your teach-in.

8. Get help covering your costs: Ask for donations from local businesses: paper, pens, poster board, paint, photocopying services, etc. If you want to serve refreshments, grocery stores often have donation programs and local businesses may sell you refreshments at cost or donate in return for a mention at your event. Many colleges also have funds reserved for invited speakers, for which registered groups are eligible to apply. You can put in formal requests to departments like political science, sociology, history, ethnic studies, gender and sexuality studies, environmental science, etc. Local organizations in your town or region may also be interested in co-sponsoring: unions, immigrants’ rights groups, environmental groups and social justice organizations, just to name a few.

9. Keep the conversation going: Set goals for your teach-in and clear next steps. We suggest having specific actions you’d like students, faculty and/or communities to take that help move us towards system change. That could be anything from a) asking your university to divest from fossil fuels and reinvest in sustainable energy to b) asking your political science or economic departments to offer classes that examine viable alternative political economies or c) connecting with your local credit union, cooperative movement, debt strikers or #Blacklivesmatter group to see how you can contribute to the local struggle.

Template Flyer

Generic Poster

Return to Table of Contents

Teach-In Film Trailers

Looking for more stimulating and innovative content to feature at your Teach-In? These films can provide a great starting point for fora and discussion at your college or university. Listed here are trailers for our partner films available for screening at any Teach-In nationwide.

Boom Bust Boom

Terry Jones (Monty Python) presents a new documentary in support of the global post-crash movement to show the link between our unstable economy and how economics is taught. Boom Bust Boom features high profile advocates for change such as John Cusack, journalists Paul Mason and John Cassidy plus leading experts including Andy Haldane, the Chief Economist of the Bank of England and Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman, Robert J Shiller and Paul Krugman. A mix of live action, animation, puppetry and song, Boom Bust Boom charts the ancient cycle of boom and bust and offers the world a solution. To bring this film to your campus, please contact Lisa at lisa (at) culturalfrontproductions.com.

The Next American Revolution

While there’s been no shortage of commentary about the structural crisis plaguing the American economic and political system, from wage stagnation and chronic unemployment to unchecked corporate and state power and growing inequality, analyses that offer practical, politically viable solutions to these problems have been few and far between. This illustrated presentation from distinguished historian and political economist Gar Alperovitz is a rare and stunning exception. Pointing to efforts already under way in thousands of communities across the U.S., from co-ops and community land trusts to municipal, state, and federal initiatives that promote entrepreneurship and sustainability, Alperovitz marshals years of research to show how bottom-up strategies can work to check monopolistic corporate power, democratize wealth, and empower communities. The result is a highly accessible look at the current economy and a common-sense roadmap for building a system more in sync with American values. Please contact judder (at) democracycollaborative.org to screen this film.

Shift Change

At a time when many are disillusioned with big banks and big business, and growing inequity in our country, employee ownership offers a real solution for workers and communities. Shift Change is a new documentary (to have its world premiere on October 18, 2012, in Oakland, CA) that highlights worker-owned enterprises in North America and in Mondragon, Spain. The film couldn’t be more timely, as 2012 has been declared by the U.N. as the “International Year of the Cooperative.” If you’d like to bring this film to your campus or community, click here.

Teach-ins focused discussion guide on Shift Change

This Changes Everything

Directed by journalist and filmmaker Avi Lewis (The Take) and produced in conjunction with Naomi Klein’s bestselling book of the same name, this urgent dispatch on climate change contends that the greatest crisis we have ever faced also offers us the opportunity to address and correct the inhumane systems that have created it.

To bring this film to your campus, please visit http://www.rocoeducational.com/this_changes_everything.

External Blogs and News Articles

What Comes After Capitalism? Upcoming Teach-Ins Can Show a Way Forward

By Gar Alperovitz and Ben Manski. April 22, 2016

Originally published in Truthout on Thursday, 21 April 2016.

An extraordinary process of change is about to explode this month on campuses and in communities across the United States. Thousands of Americans are coming together in dozens of locations to take on the question of what kind of system should replace capitalism. The process is called the Next System Teach-Ins.

Teach-ins to address the fundamental question of how to move beyond capitalism will be taking place oncampuses as well as in community centers and correctional facilities — most between Earth Day (April 22) and May Day (May 1), following kickoff events this month at the New School and the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City; and the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The largest teach-in is planned for the University of California, Santa Barbara, between April 26 and 28. Major sessions from that campus will be live-streamed into classrooms, house parties and workplaces across the world.

The idea that capitalism as a system may be coming to an end, that something new must ultimately be created, is no longer restricted to groups on the political left. Survey after survey has found millions of Americans embracing ideas far different from business as usual. A January 2016 poll of likely Democratic caucusgoers, even in a state like Iowa, found that 43 percent described themselves as “socialist” — a higher percentage than those who self-identified as “capitalist.” Eighty-four percent of Democratic voters under the age of 30 voted for the self-described “democratic socialist” candidate Bernie Sanders, and one-third of all Sanders supporters have told pollsters they will vote for the Green Party’s Jill Stein in the general election if Sanders is not the Democratic Party nominee.

Nor is the understanding that the current system is not the be-all and end-all of history restricted to progressives in general. Long before anti-capitalism found mass expression in the Sanders campaign, four years ago, in 2012, Klaus Schwab, chairman of the World Economic Forum — the annual gathering of corporate and financial leaders in Davos, Switzerland — declared: “Capitalism in its current form no longer fits the world around us.”

When the next crash comes, will we be ready to offer a clear, workable and compelling vision of how to reorganize society?

And three years ago, the Academy of Management, an august body of 29,000 business school professors and corporate advisers, met for their annual meeting in Orlando, Florida. The theme: “Capitalism in Question.” Some of the questions: What kind of economic system would a “better world” be built upon? “Would it be a capitalist one? If so, what kind of capitalism? If not, what are the alternatives?” Economist Thomas Piketty’s book on the inequality and instability endemic to capitalism was number one on both Amazon and the New York Times hardcover nonfiction list.

But what kind of system might one day transcend the traditional 20th-century models of corporate capitalism on the one hand, and state socialism on the other? And what can those who insist that the next system produce democracy, justice, equality, ecological sustainability and a culture of community do to build understanding of the kind of political and economic system and society that we want and need?

What can we do to move forward in a positive way? How do we engage the question, both practically and theoretically? How do we move beyond abstract rhetoric? These questions at the heart of the teach-ins matter to all of us, but they are particularly urgent to those born after the 1960s.

We’ve seen that urgency expressed repeatedly over the past five years, first with the immigrant rights mobilizations, then in the Wisconsin Uprising and Occupy Wall Street, next with the climate justice movement and Black Lives Matter, and today with the powerful generational justice politics expressed in the support for Bernie Sanders among millennials and Generation X. Generational politics are increasingly class politics.

Teach-ins as a strategy for helping catalyze serious change have been part and parcel of progressive change for more than five decades. Beginning in the mid-1960s with the teach-ins on the war in Vietnam and continuing on through the 1970s and 1980s with the use of teach-ins by the environmental, women’s, anti-apartheid and anti-nuclear movements, into the 1990s and 2000s with the Democracy Teach-Ins and Tent State Universities, and most recently with Occupy and Black Lives Matter, activists have periodically revived the tradition of campus teach-ins.

Teach-ins transform college and university campuses into political fora in which students, faculty and community members take collective responsibility for matters of local, national and global import. They usually involve large-scale gatherings combined with smaller, more intensive workshops. One thing that makes a teach-in different from a conference or an academic seminar is the teach-in’s focus on producing knowledge for use by participants as members of an organized, politicized campus community.

Another is the use of a “wall-to-wall” organizing approach in which every member of the community is challenged to engage in discussion and debate on the question at hand. The major waves of teach-ins of the past 50 years have gone beyond the committed choir to inspire large numbers of people to expand their sense of the necessary and the possible.

Each teach-in wave produced something powerful and new. The teach-ins on the Vietnam War greatly expanded the reach of the antiwar movement and deepened the questioning of long-held assumptions about the role of the United States in the world system. Earth Day 1970 helped launch the modern environmental movement. The teach-ins of the women’s liberation and out-of-apartheid movements transformed lives and built and expanded those movements throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s.

The Democracy Teach-Ins of the 1990s cohered, radicalized and mobilized the student anti-corporate and anti-sweatshop movements that fed into the 1999 shutdown of the World Trade Organization meetings in Seattle. The national wave of teach-ins on the Wisconsin Uprising churned movements across the country in the months prior to Occupy Wall Street, which in turn inspired its own teach-ins around the world. Similarly, Black Lives Matter inspired campus teach-ins, which then fed into mobilizing for the first National Blackout Day of boycott and protest.

Though colleges and universities are hardly the only places where the challenge is intensely felt, they are critical arenas for this debate. They have been in crisis since the 1990s. And the problems confronting students and would-be students, as well as faculty and staff, are worsening most places one turns. The University of Wisconsin system has eviscerated faculty tenure, and prominent professors are fleeing the state. Chicago State University — an institution that disproportionately serves low-income students and students of color — has closed its doors for lack of state funding. Faculty and graduate student unions have been compelled to authorize strikes in the California State University and CUNY systems. And everywhere the burden of student debt, combined with precarious labor markets, has produced two generations of Americans indentured to the failings of modern capitalism.

All of this is the result of over 30 years of deep cuts in public funding for public higher education (as a proportion of overall costs), huge increases in student tuition and student debt to make up for those cuts, and the concurrent and related corporatization of university research and services. This past year’s campus mobilizations — from the Million Student March, to the mass protests in support of Black students at the University of Missouri, to the new campaign by the United States Student Association for free higher education and student debt forgiveness — show an understanding that the crisis in higher education is part of the broader systemic crisis.

The good news is that the Next System Teach-Ins are only beginning and are only one part of the important work of many hands in preparing the way for a new society. From the New Economy Coalition to the US Solidarity Economy Network to the upcoming 2017 Democracy Convention to the Black Liberation Collective, the constitutional reform efforts of Move to Amend and more, a movement for economic and political democracy is underway in the United States.

We’ve seen state socialism and know it’s not a workable alternative. We’ve experienced corporate capitalism; it has proven itself inequitable, unstable and ultimately unsustainable. Over the coming decades, and especially when the next crash comes, will we be ready to offer a clear, workable and compelling vision of how to reorganize society?

Copyright, Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

Participant comment by Craig Alciati:

I just returned from the Teach-in at the University of Minnesota put on with the School of Nursing there. As a Nurse since 1994 it gave me a very wonderful feeling to see Nursing as a profession stepping in to help create a healthier system. If you have hope for a better future don’t wait come listen and contribute. Silence is golden, but participation is needed.

The Next System teach-in was both welcoming and very positive. A huge breath of fresh air. I am not a big one for the doomsday idea. Personally I see humans a bit like dandelions. The odds of us all going away anytime soon seem small. At the same time I seem humans as orchids too and I really love the mix of dandelions and orchids and all the other flowers so the project of fostering a beautiful Eco-socio-environment is an exciting activity and reason to get out of my comfort zone. I do think health care providers are in a special place in that for the most part the general public has a good level of respect and trust in us as a group. It is safe to say our political and legal counter parts has lost much of that. We have a real sweet opportunity to bring all the right players together, clear the air and uncover a better path for today and the generations to come.

The facilitators and organizers at the Katharine J. Densford International Center for Nursing Leadership did an excellent job of creating an open atmosphere where everyone was free to speak and did. People listened and engaged in a very respectful and humble way. Beautiful, really.

Maybe part of why it seemed so refreshing was due to the function I attended the previous Saturday. I am not a political party person. I always voted even when I lived out of the country for 12 years. Of course I always expressed my opinion and listened to others when it came to ideas about our social, legal and political state, but I never engaged in the parties. Last weekend I was a delegate and I was quite disappointed to say the least. Let me simply say it did not create in me a welcoming or hopeful atmosphere. After six hours to make one meaningful decision I had to leave to pick up my daughter. So I had to leave before the most important process had even started. Not only that by maybe 50% of the other attendees had left before me. I understand the bigger and older an body gets the slower it moves, I see the same thing in the mirror everyday. But that should be motivation to act not dig our heals in. I can really see how the Next Step project can be an incubator of many new and “renewed” ideas and solutions. I look forward to the unfolding.

Return to Table of Contents

Rethinking Prosperity on UW Seattle Teach-in

by Caterina Rost, May 11, 2016

Originally published March 8, 2016 by Rethinking Prosperity.

SEATTLE, WA – The realities of growing inequality, political stalemate, and climate disruption just scratch the surface of global issues we face today. It is clear that the current system doesn’t work for the vast majority of people on the planet, and we need to work toward something better.

At the same time new ideas and movements are challenging long held boundaries of what’s politically possible, illustrated by the success of Bernie Sanders, the resonance of #BlackLivesMatter, and campaigns to block the fossil fuel economy.

In order to build a world that puts people, communities and the planet first, we need to imagine what’s possible. We invite you to help us build a learning community for realignment of the economy, environment, and democracy so that all three systems work better for people and the planet.

Read the full article from Rethinking Prosperity for video and photo archives of the University of Washington-Seattle Teach-In.

Next System Teach-in Participants Call for Real Democracy, Equitable and Green Economy

By Caterina Rost, May 27, 2016

Originally published in Rethinking Prosperity

On April 25, students, community members, faculty, and staff came together for the Next System Teach-In at the University of Washington. The event was attended by hundreds of voices united in their common cause of creating a more equitable, democratic, and sustainable world.

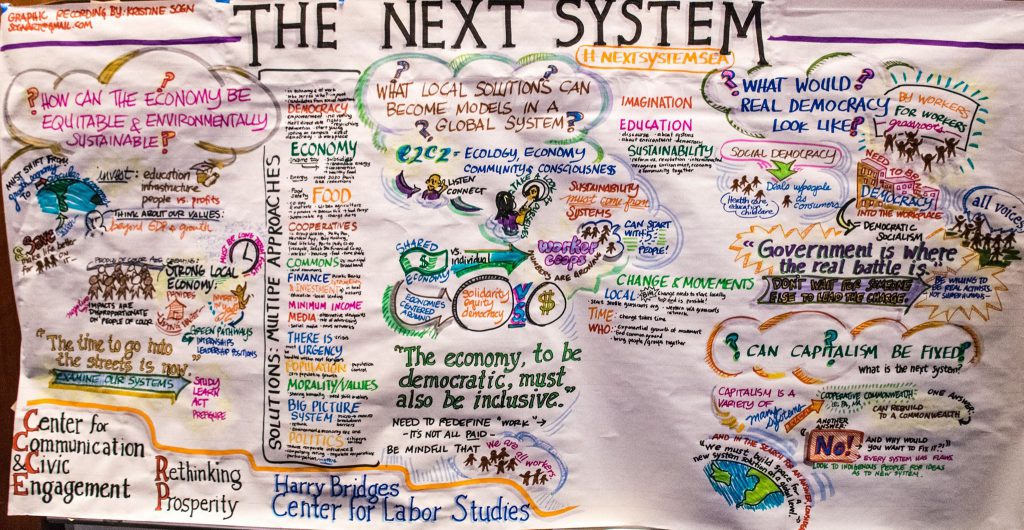

The Teach-In was structured around a series of short panels, made up of three provocateurs—speakers who provided short and thought provoking answers to the central question posed to each panel [Watch the Videos]:

- How can the economy be equitable and environmentally sustainable?

- What local solutions can become models in a global system?

- What would real democracy look like?

- Can capitalism be fixed?

- How can we move beyond “Economy vs. Environment” and “Democracy for the Few”?

The provocateurs’ included local thought-leaders like Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and Washington State Labor Council President Jeff Johnson, students and alumni like Nate… and Sarra Tekola from Women of Color Speak Out, and Rethinking Prosperity’s own Professor Lance Bennett.

After the panelists shared their thoughts, the audience participants got a chance to discuss their answers as well as the broader question in small roundtable discussions where they could record any key insights from their discussions on sticky notes. The sticky notes were then incorporated into the graphic art recording of the whole event (above). Here is a visual representation of the main points of interest to participants:

The audience comments centered on problems that are contributing to the system failure, questions, and possible solutions or steps towards the next system. The key questions that audience members brought up were:

- Should we pursue reform of the system or system change?

- How can we change the incentives for the rich and powerful?

- What is growth and poverty?

- How can politicians of the City of Seattle improve the local economy so that we can replenish all of our natural resources and use green-only energy alternatives?

- How can we make changes that don’t further alienate people who marginalized?

- How can we set things up so that the easy and efficient thing to do is also the sustainable and equitable thing to do?

Comments from Audience Discussions

Two of the central problems that received a lot of attention from the audience were the current U.S. political system and the global economic system. One audience member noted that the top “1 percent have way too much political power.” Possible reforms that were mentioned ranged included:

- Decentralizing power

- Pushing for campaign finance and electoral reform

- Organizing direct actions

- Running social movement candidates in elections,

- Establishing local neighborhood councils

- Public banks

- Make voting easier and more impactful (e.g. by making election day a paid holiday, lifting voter restrictions on felons and prisoners, supporting national direct vote movements, simplifying voter registration, and providing voting places on campus).

The character of the global economy underscored the need to rethink the current system. As audience members noted, while more wealth leaves poor countries every year than enters them, 40 percent of the world’s wealth is housed in tax havens. Also, one comment stated that the “economic crisis is linked to [the] ecological crisis because [the] economy is all about making money” and not about the sustainable use of our environment and natural resources. To address these challenges, the audience suggested that we need to:

- Include externalities in our economic equations

- Increase the democratic control of economic production, for example by establishing work councils.

- Pass a Green New Deal

- Increase the income tax rate on high earners and provide a guaranteed or minimum income.

- Similarly to the Panama Papers, publicly list the names of the 62 people who own as much as the bottom 50 percent of humanity to encourage better values.

Most importantly, however, we need to build a network to bring together and link groups that are working on the same or complimentary projects and issues (e.g. youth, labor, people of color, environmentalists, etc.) and to encourage solidarity and collaboration between them.

When considering whether system change is possible, one audience member wrote, “big change is possible, but it needs to start at the local level.” Many other commentators seemed to agree as they discussed various types of cooperatives and listed specific examples as possible change agents. These cooperatives can be instrumental in the quest to “reclaim the commons” (e.g. municipal broadband) and to “keep lands from being corporatized.” Some of the examples of cooperatives and “hyper-local decentralization” that were mentioned are the Buy Nothing Group, the Nextdoor app, the Beacon Hill Food Forest, Local Investment Opportunity Networks (LIONS), and the Northwest International Communities Association (NICA.NWCommunities.org). One comment suggested that there should be a reality TV show about cooperatives to make them more popular. Finally, an audience member noted, “local development should prioritize local companies and socially responsible business when possible.”

UW community gathers for The Next System Teach-In

By Madelyn Reese,Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Originally published in The Daily of the University of Washington

More than 100 students, professors, and community members gathered in the Walker-Ames Room of Kane Hall on Monday afternoon for one of many panels featured in “The Next System Teach-In.”

The event, which ran from 1-8 p.m., gathered activists and experts to discuss a wide range of questions like “How can the economy be equitable and environmentally sustainable?” and “What would real democracy look like?”

The teach-in was organized by the Center for Communication & Civic Engagement, the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, and Rethinking Prosperity as part of “The Next System Project.” The project is a multi-year initiative “aimed at thinking boldly about what is required to deal with the systemic challenges the United States faces now and in coming decades,” according to the project’s website.

The questions the event aimed to discuss were difficult to grasp in their entirety, which was acknowledged by many of the panelists. Some proposed their own solutions, while others suggested that in order to find the way to a solution, the problems needed to be broken down to their basics.

“Can capitalism be fixed?” was a particularly divisive question. John de Graaf, co-author of the anti-consumerist book “Affluenza” and “What’s the Economy for, Anyway?” spent his allotted 10 minutes on what he believed was a concrete solution.

“There are enormous differences between capitalisms,” de Graaf said. “It’s not one system, it’s a variety of systems. We need a different model. And we have a historical one here in the U.S.”

De Graaf cited the Cooperative Commonwealth, modeled after the Washington Commonwealth Federation, that was established in the 1930s and ran through the Washington state Democratic Party, successfully electing candidates to seats in the legislature and in Congress.

“I think the next step for the Bernie Sanders people is to rebuild the Democratic Party as a commonwealth federation,” de Graaf said. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel, we have a lot of ideas here.”

Sarra Tekola, a climate justice activist from Women of Color Speak Out,took a different stance.

“The system of capitalism always hurts people,” Tekola said. “Should capitalism be fixed? We’re asking the wrong question when we ask that. We’re not going to reform our way out of this.”

While Tekola did not present suggestions as to what might be an alternative, she affirmed that she was not interested in any pre-existing system.

Those at the teach-in also heard a variety of perspectives from speakers who took on the question of “What would real democracy look like?” Michael McMann[CQ], director of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, put forward the idea that democratic activity cannot be limited to the public realm.

“Democracy has to involve ourselves as workers, as producers in society,” McMann said. “If you’re not participating in democratic activity in the rest of your life, how are you going to take part in democracy in the public realm?”

He argued that since most of our time is spent at work, the first place to start would be to bring democracy into the workplace, involving workers at the grassroots level.

Meanwhile, former Seattle city councilmember Nick Licata struck a compromise between McMann’s workplace idea and that of Reagan-era politics.

“It took workers to go out and protest. … But in the end, it was the law that changed,” Licata said. “If you don’t have a government that can change your working conditions, then what you do is you shrink the sphere in which you can live in a democratic society.”

Shrinking the sphere, Licata elaborated, means shrinking the government.

“There’s only one government, so it’s an easy target,” Licata said.

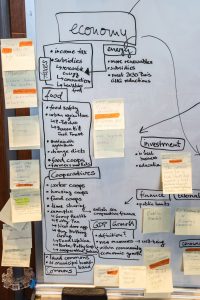

To cope with the variety of ideas and opinions drifting around in the room, the teach-in was organized to allow 10 minutes of discussion after each panel. Students and community members gathered around to discuss the speakers, their thoughts, and any further questions. They wrote their key takeaways and questions on sticky notes after, which were then organized on a white board near the front of the room by volunteers.

Devon Gonzalez-Yoxtheimer was one of those volunteers, as well as a student of Lance Bennett, the director of the Center for Communication & Civic Engagement and a UW professor of political science and communication, as well as a key organizer for the event.

“Our job is to create order out of the chaos,” Gonzalez-Yoxtheimer said.

He and other volunteers created flow charts of questions and answers from the table and began organizing them by topic. Audience members could then come up to the front of the room and see the ideas of other attendees.

Other students of Bennett’s were present at the teach-in, including sophomore Hayden Kazmark and junior Cassidy Buchholz.

After the third panel about imagining what a “real democracy” might look like, the two reflected on their impressions of the speakers.

“It was interesting; there were perspectives you don’t hear much of, especially the immigrant or native perspective,” Buchholz said, referring to the presentation by Edgar Franks, the civic engagement program coordinator at Community to Community Development.

“I think it’s great to see how many types of people have come together for this,” Kazmark said.

Return to Table of Contents

The Next System Project sparks debate with inequality workshop

By Kathryn Cargo, April 21, 2016

Originally published in The Shorthorn of University of Texas Arlington

Capitalism and other systems were discussed during an inequality workshop.

CAPPA Ph.D Consortium, a student organization for doctoral students in the College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs, hosted the workshop Thursday.

The workshop is part of a national initiative called The Next System Project, which has encouraged university students to discuss issues they are concerned about, said Ali Adil, president of the consortium and urban planning and public policy doctoral student.

“We need to think about post-capitalist society and what might that look like,” Adil said.

Adil said he hoped the workshop encourages the UTA community to start conversations about issues that concern them.

“The idea is to create momentum for some student-led organizing, which invites the attention of the larger community to issues that concern all of us,” he said.

Adil used climate change, ecological degradation and fracking in Texas as examples of issues that need to be addressed, he said.

“Why not talk about it and build strategies to overturn those practices, because it concerns homeowners, it concerns people who are living here,” Adil said. “All these issues are tied with the larger issue of political economy.”

The workshops introduce a new framework of problems in systemic thinking, Adil said.

The students discussed various systems that exist in society during the workshop, such as the United States prison system, said Flora Brewer, urban planning and public policy doctoral student.

“The idea that we’re trying to get at is we all live inside of systems, political systems, economic systems, social systems, environmental systems,” Brewer said. “We’re not always conscience of the operation of those systems all the time.”

About 30 percent of the U.S. population has a criminal record, Brewer said, which hurts society. The percentage is high because there are too many ways for an individual to be criminalized, she said.

U.S. society follows the broken window theory, history doctoral student Robert Caldwell said. The theory states that every small crime has to be policed or major crimes will come from them, he said.

After the workshop, the documentary “Boom Bust Boom” about the financial crash in 2008 was shown.

The Next System Project workshops will continue from 3:30 to 6 p.m. tomorrow in the College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs building Room 201.

Return to Table of Contents

Videos and Media

Produced by The Next System Project

Powered by YOU: Members of UW-Madison community explain why they’re hosting a teach-in

NYC Convening Opening Plenary

The Next System Inaugural Teach-Ins: Highlights from NYC

Noam Chomsky talks to the Next System Project teach-ins on the power of campus organizing

How to host a Next System Teach-in

Other videos, livestreams, radio shows

Next System Project Teach-in, Pinchot Univ. Seattle May 4th, 2016

System Change is Coming: Gar Alperovitz gives Keynote Address at UC Santa Barbara Teach-In

View all of the University of California at Santa Barbara livestreamed videos here.

Edgar Franks - What would real democracy look like? Speech at UW-Seattle Teach-In

View all of the University of Washington Seattle livestreamed videos here.

Worker Co-ops: A Strategy for Building the Next System

Published by Todd Boyle, May 10, 2016

Featuring Alison Booth Gribas, Melissa Young, Tim Palmer, Deric Gruen. Moderated by Syd Denise Fredrickson.

Tufts New Economy Teach-in: Signs of System Shift

Published February 29, 2016

Featuring Neva Goodwin (Global Development and Environment Institute), Alice Maggio (The Schumacher Center), and Carlos Espinoza-Toro (JPNET) discuss the signs of a system shift as part of a “Urban Environmental Policy and Planning Colloquium” and the “Tufts New Economy” group.

National Teach-Ins Coordinator Dana Brown on ACRONYM TV Podcast: “From the Ashes of Capitalism, The ‘Next System’ Seeks To Rise”

Hosted by Dennis Trainor, Jr., April 20, 2016

There is a growing consensus that the crisis facing us across multiple fronts: environmental justice, racial justice, wealth inequality and more are both interconnected and systemic, meaning that Capitalism not only has no answers for these crisis, but these myriad crisis themselves are built into the system.

Dana Brown, the National Teach-Ins Coordinator for the Next System project, joins Dennis for an interview about the end of capitalism and navigates the “reform or revolution” framework during the height of primary season.