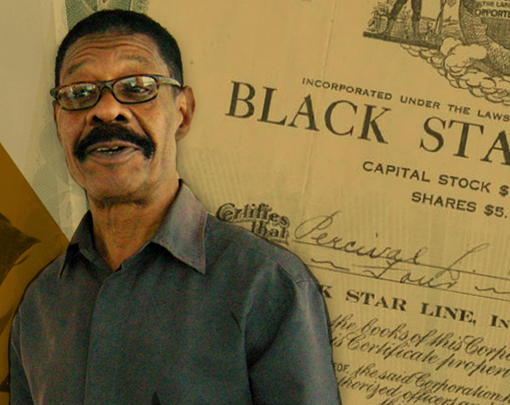

This week on the Next System Podcast, Dr. Andrew Cumbers sits down to discuss his work on public ownership and how such paradigms can pave the way for democratic controls over the economy. The Democracy Collaborative’s Director of Research, Thomas Hanna, joins the conversation as well.

Subscribe to the Next System Podcast via iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, or RSS.

Adam Simpson: Welcome back to the Next System Podcast. I’m your host Adam Simpson. Today I’m joined by a special co-host, Mr. Thomas Hanna, the Democracy Collaborative’s Director of Research. Thomas has written extensively about public ownership in the United States, which is our topic of conversation today in addition to the public ownership in Europe and the UK. Additionally, Thomas has a book coming out on the subject in 2018.

Thomas, thank you for joining me.

Thomas Hanna: It’s my pleasure.

Adam Simpson: And we’ll be interviewing Dr. Andrew Cumbers about alternative ownership models and economic democracy.

Andy, welcome to the Next System Podcast.

Andrew Cumbers: Thanks for having me. It’s lovely to be here.

Adam Simpson: As an introduction to our listeners, Andy is a professor in regional political economy at the University of Glasgow, in Scotland, and a leading expert in alternative forms of ownership. He’s the author of Reclaiming Public Ownership: Making Space for Economic Democracy, Repossessing the Future: a Common Weal Strategy for Community and Democratic Ownership of Scotland’s Energy Resources, and a paper for the Next Systems: Possibilities and Proposals Series titled Diversifying Public Ownership.

Recently he helped produce the British Labour Party’s Alternative Models of Ownership report, which lays out the case for increasing worker and public ownership as a way to combat inequality, political disenfranchisement, underinvestment, and create stable economies. Andy, we’re very glad to have you.

Andrew Cumbers: Great to be here.

Adam Simpson: So, just to start by defining the problem. Andy, you’ve done a lot of work on alternative models of ownership but before diving deeper on this I wanted to ask the obvious question—about the traditional forms of ownership. How has the traditional political-economic system failed and what role does ownership play in that failure?

Andrew Cumbers: Okay. I think there’s three interlinking things I’d say there. If you look at the broader, global political economy, I think there seem to be three critical issues. First is this massive widening chasm in inequality between the elites, whether you want to call them 1 percent [or not], and everybody else. That’s a global phenomenon, it’s not just something that is happening in the US it’s happening everywhere. Of course, it’s more complex than that but I think if we’re thinking about economic democracy and questions of ownership, I think this is critical. You’ve got an elite class increasingly making most of the key decisions about the economy, that inform and shape our lives. So for me, ownership is first and foremost about that decision making process. Who owns and controls it?

The second thing that comes out of that is a sense in which we’re living in an age where democracy is itself being downgraded. Perhaps devalued is the wrong word. But there’s a sense in which anything that reflects a really important issue around the economy, is increasingly something that is no longer open for public debate or the democratic domain.

Jacques Ranciere, talking about the political system in which the key decisions that affect our lives are being dominated by the elite, refers to the term “the Partition of the Sensible,” which when the big sets of policy decisions are far too important to be left to masses of people; they need to be technocratic; they need specialist expertise. And that’s code for “We need to take control of the economy, away from any democratic agency.” It’s basically that decisions are taken on behalf of private corporate vested interests. I think that’s the key point there.

And I think there’s a closing down of public debate around the economy and what it’s for that goes with that— you see whenever a popular government is elected, there’s straight away an attempt to close down their options. We saw this with Greece, it will be interesting to see what would happen if in the UK if the Labour government got elected. They would have control of their own currency, which would be an important thing.

But nevertheless,I think there is a “post-democratic,” as Colin Crouch puts it, or “post-political” turn going on in terms of how the economy is ruled and governed. You could say, “Well, capitalism has always been governed and ruled by elites.” But I think there’s been a ratcheting up of that undemocratic elite control of key economic decisions affecting our lives. That’s why ownership, in a broader sense, is important, why ownership of the economy and the democratization process of the economy is important—and what we want.

But the third critical thing, the key problem of our time, of course, is climate change. And climate change and getting it right from the point of view of social-ecological justice is again, all about ownership. Who is owning the decision-making process around dealing with climate change? Now I know in the US you’re having a big problem in public policy terms, in getting any kind of policy initiative on climate change to be mainstream. But I think that even in Europe—where tackling climate change is a mainstream public policy concern that cuts across the political divide—a lot of the debate on the strategies and policies are once again driven by an elite, which is proffering market-based solutions, which quite clearly are going to come up short.

And so there’s a third pillar of why we need to talk about democratizing ownership, it is really about who controls decision-making processes around dealing with climate change. And I think that needs to be done in a much more democratic way that involves a broader sense of community around that decision making process. Because I think we have a very liberal elite view of how you deal with climate change, which leads to market solutions. Which I think, even when they are effective, are really very inefficient ways of kind of dealing with it, and then of course they often create all kinds of market failures by developing markets for carbon and so on. And actually often have detrimental effects from what’s intended.

And I think a lot of that reflects the fact that the whole climate change mitigation business is still a growth project for the elite. Rather than a serious problem about “how do we transform our planet, community and society?” And that takes us into the key issues that the Next System Project is concerned with. For me again, it comes back to [an economy that’s] democratic, deliberative, shared. We need those active debates, and we need those antagonistic debates, to come back in. Rather than pretending there is some faux consensus over climate change in particular, or any other situation.

And I think all those things together lead to sort of an alienation for a lot of people. Particularly when they see living standards falling. They see the next generation is going to be worse off than them in loads of ways. I think even people who wouldn’t necessarily see themselves as left, progressive people. But they care about what’s happening. Or are angry about these things. And that takes, of course all kinds of forms. Trump here, Brexit in the UK, and so on.

Thomas Hanna: Two terms that you’ve used to explain or address the failings of the current system are “economic democracy”

and “democratic economy.” Can you talk a little bit about economic democracy and a democratic economy and what those terms mean?

Andrew Cumbers: Well, conventionally, we thought about economic democracy usually as meaning two things. Firstly, employment relations and relations between employers and the work force. Issues around unionization and encouraging more distribution of economic decision making by bringing trade unions and labor unions into the equation.

The other side of traditionally thinking about economic democracy is to think about that in terms of cooperative organization. Collective ownership. Employee ownership of the workplace. So I think the traditional concern with economic democracy has been about thinking about it as a collective project around the workplace, and around a particular a set of actors, if you like—a kind of old industrial, largely white, working class, constituency. And the kind of economic democracy I think we need to be talking about actually moves towards a much broader conception of what economic democracy is. It goes beyond traditional collective forms of agency and action in the workplace, whether it’s around trade unions or whether it’s around mutualization and cooperatives. Perhaps [we should be talking] about the democratic economy rather than economic democracy.

[It’s important] to actually beginning to think “what should economic democracy really be about?” For me, it’s about empowering and tackling social justice and inequality, on the one hand. But it’s also about individual empowerment. And I don’t mean that in a negative sense, thinking about the individual and their rights in the way that mainstream economists would, as sort of selfish rational individuals. I mean about thinking about the individual as part of society, and its ability to deliver what some heterodox economists have called “choiceworthy lives.” I don’t like that phrase. But it’s about peoples ability, whatever background you come from, to have some kind of control or autonomy over your life and your work and your conditions of work. But also to be able to prosper and flourish.

I think that’s often been left out of a lot of leftist discourses around economic democracy. So it’s about prosecuting individual economic rights, but also when you begin to talk about it in those terms, it’s also about people’s rights to participate in the economy, as individuals. And if you accept, as I do, that we’re not a collection of individuals, but basically that individuals are firmly embedded in society and communities—when you begin to talk about individual rights in this way, it doesn’t lead you down a mainstream economic path or even the neoliberal version of what the individual is. It’s a way to say “Well actually if we’re really concerned with individual economic rights, those are fundamentally also about community rights.” Thinking about the individual, for me, leads to thinking about the collective as well.

So that’s the first part of how I would see economic democracy, differently than what’s gone before. The other thing I think that’s really important, the other side of it, is really the whole terms of public engagement around the economy. Coming back to what I said in the beginning, I think one of the big problems isn’t just that ownership is increasingly privatized or corporatized or financialized, but it’s also that the control of decision making that goes along with that has becomes corporatized, financialized, etcetera.

So I think one of the big issues that we have to confront is: how do we get more public control over the decision making? And even deliberative economic debates, discussions and so on, about how the economy works. So the second, sort of, broad part of it, which I think is new, is to think about public participation and engagement, and how we motivate new forms of that happening, so that we can have a more broadly democractic ethos.

Those ideas need to come back into the thinking about how we think about the economy as a more democratic entity. So for me it’s moving from those older conceptions of economic democracy to really asking questions about how to democratize the economy in fundamental ways.

Thomas Hanna: I think we’ll come back around to the rights and the role of individuals within the economy a little bit later on, but for now I know that some of your colleagues at the University of Glasgow, you’ve devised and index to measure economic democracy and to compare performance internationally. Could you speak a little bit more about this project? And specifically what’s strong and weak performance on the index tells us that traditional economic comparative measures like GDP can’t tell us?

Andrew Cumbers: Well the index really is an attempt to measure the kinds of things I’ve just been talking about. So we’ve constructed an economic democracy index, as far as we know it’s a new attempt to do this. Our model was really the human development index that the UN created, which is obviously a global analysis of national performance against human indicators, so we’re trying to do the same. Our ambition is the same for economic democracy, so we started with the OECD countries, most of those in the global North, but that’s a pragmatic decision—we want to extend it beyond that, but decided to go [first] for those countries where the data’s available to do the kind of thing we want to do.

What we’ve done with the index is to create a composite measure of these different facets of economic democracy that I’ve been talking about. One component is these individual rights—mainly around the workplace and what rights does an individual have in relation to work, in relation to employment, welfare rights, those kinds of things.

Second component of it is the traditional conception of economic democracy around collective bargaining and the significance of cooperative and employer ownership forms.

The third and fourth components are quite difficult to get a handle on and they’re the ones we struggle with. Our index—we’re not putting this forward as a definitive view or statement—but it’s really there to kind of prompt debate in many ways.

So the third and fourth. The third is really an attempt to get a sense on how the distribution of economic decision making happens across geographical space and across sectors. So we’re looking at things like the concentration of industry. We view indicators on the level of public spending, which is a quite useful indicator of the relation between public and private in an economy.

And then the fourth indicator is really trying to get to grips with how the macro economic governments of different countries operate. You know, what’s the role of the Central Bank, how independent is it? We’ve looked at things like corruption and the role of indexes around corruption. We’ve brought some of those things in. We’ve looked at the extent to which different social partners are involved in economic policymaking at the national level. That happened in certain Nordic countries. It doesn’t happen to, at all, in the US, or happens to a very limited extent in places like the UK.

So it’s those four things and we bring them together to construct one index.

What does it tell us about economic development? Well I think the first thing it says, is it does reinforce the things that we already know. That in some ways economic democracy in government is strongest in the Nordic countries. It’s weakest in some of the Anglo American countries—the US is second bottom of our index. We weren’t particularly surprised by that. If you look at the other countries down at the bottom in these areas they tend to be Eastern European countries. They score very poorly and we think that’s because an active civil society and active set of institutional government structures around the economy is probably relatively absent in those countries, partly because of the collapse of communism and the failure to put any real serious institutional structures in place.

The one exception is Slovenia, which I think is interesting—we’re doing more work on that in qualitative terms to find out what’s going on there. There might be a legacy of older forms of Yugoslav of decentralized self-management and cooperative systems that’s coming through in there. And Slovenia is often seen as a more social democratic version of an Eastern European state than some other countries.

The other countries that don’t do so well, especially since the crisis, are some of the Mediterranean countries in Europe, where I think some of the labor market and some of the regulatory changes that have been introduced after the financial crisis downgrade the conditions of work. Places like Greece and Spain is relatively poor position.

How does it match up with GDP? I think I would say there’s no clear, strong, positive statistical relationship either way. You can’t say countries that have strong levels of economic democracy perform badly in economic or GDP terms or that they perform well.

What we have found, though, is quite striking. What we found is that statistically there is a really strong relationship between inequality and economic democracy. We found very strong relationships or correlations between economic democracy, poverty, and even productivity with the index. So countries with high levels of economic democracy tend to have lower levels of poverty and lower levels of inequality. But there’s even some evidence that countries with high levels of economic democracy do very well in productivity besides.

But the really strong statistical relationship is with inequality. It seems that economic democracy is a very good predictor of whether a country has high levels of inequality or not. So we think that in itself is a quite interesting and important finding.

Thomas Hanna: And just to clarify that, high levels of economic democracy correlate to lower levels of inequality?

Andrew Cumbers: Correct. Very strongly and at a highly statistically significant level. I’m not a statistician but I can tell you that’s one thing we can say definitively.

Adam Simpson: So often in your work when you’re defining public ownership, you’re talking about including cooperatives and worker and community owned enterprises. What are the benefits of that approach and in the current political economic context, how do you think about scaling up these alternative forms of ownership?

Andrew Cumbers: If I go back a step to thinking about when I started to write the book and what was motivating me, one of the things I was concerned about was—and this might reflect the UK context more than the US—that public ownership up until very recently had a very bad reputation, not just with conservative commentators, but with new Labour in particular in the 1990’s. Well, right up to the financial crisis when it suddenly rediscovered the merits of naturalizing the banks.

New Labour was very anti anything to do with public ownership. It was discursively portrayed by that kind of Blairite project as part of an old way of doing things. Public ownership reeked of state intervention. It was something that was seen as passé by a lot of people on the center left, across Europe, actually, as well.

One of the reasons I think it was easy to just dismiss it in those terms was because public ownership in the UK was associated with a particular model: a centralized, very bureaucratized state owned model. Which is what we had in the UK for the heyday, the last big public ownership wave in the UK, which happened at the end of the second world war in the 1940’s when the first huge majority Labour government was ever elected. They had a huge nationalization program. And that program, although it had its merits, what it did was nationalized huge swaths of Britain industry. Coal mines, most of the utility sectors, even the Bank of England was nationalized. And many people on the left saw that as a very good thing and a step forward.

But actually the model that was chosen was a very centralized bureaucratic model. It basically took whole sectors of the economy under state control, but it didn’t really open them up to democracy or any kind of real citizen engagement either. Either by the workforce or by the ordinary citizen, or user of those services.

There was a distrust, by the hierarchy that introduced this form of nationalization, of anything that smacked of allowing a kind of grassroots democracy or any semblance of bringing people on board. There was a kind of elite, even though it was a liberal elite, trying to modernize the British economy and deal with social justice issues, and they were distrustful of anything that could be portrayed as kind of syndicalist, you know? So that whole model—it was called the Morrisonian Model after Herbert Morrison, who was the minister responsible for the framework—was very top down. Actually, most of the people running the new nationalized industries were from the commercial private sector—there was very little involvement with trade unions. And no real semblance of government structures that would encourage any level of democracy.

So the nationalized industries that we had in the UK were these very centralized entities. They didn’t really generate any kind of engagement with the broader public in these sectors in the way they might have done. And so by the time you get to the 1970’s, the British economy is experiencing a crisis, as part of a broader economic crisis at the time. When the neoliberals come along with their solutions of privatization, they’re very easily able to caricature all these naturalized industries, as a kind of heavy state infringement on the true workings of private enterprise. And if only we can lift the burden of state control we can unleash the economy to enterprise and market forces and entrepreneurialism.

That whole dynamic, that whole rhetoric was very powerful. I don’t know that the broad masses of the British public completely bought into it, but nevertheless there wasn’t the kind of identification or sympathy with these old nationalized forms of industry that you might have had in different circumstances.

I think this time around, if we are going to see a big project of renewed public ownership in the UK, one of the things I’ve been keen to emphasize is that we need to think about very diverse and varied models. We need to move away from a very centralized state model in the first place.

Another important thing is to encourage diversity, more localized forms of ownership that are closer to citizens, wherever possible. But we do need a mix. You asked about how things get scaled up: I think that’s the wrong question to ask, actually. Because I think we need to decentralize where we can, but we need a multi-scalar approach whereby there are clearly some big solutions to our problems that need national, even transnational regulation. And probably do need some level of state bodies overseeing them. So if you’re going to tackle climate change, what ideally, what you would have is some sort of nationalized public entity across the whole of the European union, for example, that runs the grid.

Within that, then you can have localized forms of producing power. But you’d still want centralized state forms of ownership to control them. But those can still be democratic by having multistate models.

Public ownership is being dismissed by a lot of anarchists—there’s often been a bit of a split between social democratic top-down state vision of the world and a kind of grassroots, anarchist, cooperative model. And I think that kind of division is very unproductive. The point was valid about creating these nondemocratic structures that were still other ways of running things by the elite. They were spot on, but I think in a complex, global society we can’t move to just these nice, very decentralized forms of economic government without broader state structures.

So for me using a broad definition of public ownership was a deliberate, slightly provocative challenge to that kind of anarchist tradition to say “I think we still need the state, but we can have a diverse state.” One of the terms I quite like is the idea that we should be looking at ways of ‘commoning the state.’ So for me, I like the term public ownership because it sets itself up in opposition to private ownership and that’s the key. That’s the key thing we need to think about. But we need to think about the public as not really inseparable from the commons. The public needs to be about creating democratic collective structures. Public is a useful term to use if it encompass all these diverse things.

So the public becomes both state and non-state forms of collective ownership.

Adam Simpson: I want to come back to the idea of reclaiming the individual, especially reclaiming it from the political right. In the United States there’s this conception of individual liberty as very much tied in to private ownership of productive assets. But you suggested earlier that economic democracy needs to be reconceptualized for the 21st century, where the right of the individuals to participate in the economy, supersedes the rights associated with ownership. Can you talk a little about what kind of liberty and freedom means in the context of ownership and participation?

Andrew Cumbers: One of the ways of looking at this that I really like—this goes into the realms of philosophy that are probably beyond me—is the distinction between negative freedom and positive freedom.

A negative view of freedom is—and I think this is where the right comes in, is a view of freedom that’s almost anti state, or anti-anything that touches the individuals right to do what they like.

Whereas a positive view of freedom, which I think is the one we want to emphasize, is thinking about your individual emancipation. Your rights to do things. Your rights to have self-governance. I think that’s a fundamental distinction there because one of the people I’ve been getting into more is a guy called David Ellerman, he’s very influenced by John Stuart Mill. And they developed the idea that the individual should have the right to decide what they do with their own labor, as a fundamental right.

And that takes precedence over the individual rights—for example, over property rights. And I think that’s a really important place to start in trying to reclaim this sense of the individual. Because a lot of the debates about the individual and liberty are, in the US but also in the UK, about property. You know, “Get off my property.” “My property.” “I’m an individual I own property therefore you’re infringing on my property.” And that extends into the firm. “Hey, it’s my business.” “It’s up to me what I do with my business.” Even if I’m employing 20 or 30 people in really poor working conditions, that’s my fundamental right as an individual.

That’s just tied up with property rights, with your sense of property. But if you take a step back from that actually and say “Well, yeah we believe in individual rights but it’s actually the individual’s right to have control over their own labor” these kind of positive rights become paramount. They take precedence over property rights.

And when you start thinking of it in those sorts of ways, in the workplace, that leads you into cooperativism and employee ownership, given that we don’t have a society where everybody works for themselves. We might move to that, or more towards that, with the gig economy and everything, but when most workplaces remain collective, then it really becomes, “Well, how do you protect an agenda of individual rights to your own labor when you’re working collectively with other people?” It means you can expect a certain set of standards. I think this is where things like the idea of a basic income comes in, because that gives you a bit of freedom in how you sell your labor.

But Mill and Ellerman would go a lot further and say “Well, actually, if you accept individuals are the ones who should have ownership of their own labor, then that takes you in the direction of employee-ownership.” And that links back to the individual I think, in a really nice productive way. I think the left needs to jump on this kind of argument.

So I think employee ownership, which I think is a big thing that you have been pushing here, if it is connected to a narrative of the individual and liberty, in that kind of way, can broaden the tent a little bit here. One of the things I’m quite keen to do is develop new sets of identities and associations and go beyond the usual suspects to develop bigger sense of economic democracy.

So I think that’s why these terms are important. And the left has neglected them. Somewhere around the the end of the 19th or the beginning of the 20th century, the left began to get too much tied up with collectivism and forgetting what that meant, for actually thinking about the individual and liberty and so on.

Adam Simpson: Somewhat in the same vein, and going back to something that you had said before: you’ve argued against centralization and top down models of public ownership and this has a lot to do with liberty, and the individual, and self-management and the rights of people within enterprises. But can you talk a little bit more about decentralization, both in terms of enterprise design, but also in terms of politics more generally. Britain and the United States have very different political systems and in some ways United States is more decentralized in the political system and that allows for certain experimentation with ownership forms and different collective models than may be possible in the British context.

Andrew Cumbers: I think I take the view that you would want to encourage decentralization of public ownership on democratic grounds that clearly the more decentralized and localized things are, the more they are connected to citizens’ everyday lives. And you feel you have more control.

Of course, there’s lots of sectors of the economy where decentralized forms of diverse public ownership make a lot of sense. Take renewables—the whole way that the renewable sector needs to be reconfigured is around local diverse forms of energy. We’ve had a very centralized energy system. Big power. Whether that’s carbon or nuclear. And if we move away from that it does offer the opportunity to actually allow for more community based decentralized forms of ownership.

But I think you have to be a bit careful here what you wish for. The US is a really good example of both the possibilities of federal decentralized systems can give you, but also the kind of dystopias. If you think about the history of the South, and not being an expert on these things, it seems to me you need to kind of somehow recognize the tension between encouraging decentralization but also you still need some sort of universal set of principles and rights around that don’t allow things to get out of hand in a particular place.

For the reasons I talked about earlier, there are clearly some areas of public policy where you need bigger scale solutions and overall energy grids. Again you’d want those to be nationally run and in state control. But I think there’s certainly a lot of scope for much greater decentralization of ownership that we’ve had in the past. And I know here at the Democracy Collaborative, you’re very committed to get community based solutions and I think that’s really important. Particularly in plugging in employee ownership to the broader community. And certainly, I think, you would want the kind of localized forms of public ownership that can help to sustain local economies. You don’t get to that at the moment, except perhaps in certain places.

So I think that’s all very important—but I think you’ve got to maintain universal principles. I’m actually keener on something called—maybe I’ve still got to find the right word for this—de-centering rather than decentralization. De-centering is actually shifting decision making away from its concentration in elite groups. By making sure that you have different institutions, different organizations that contribute to economic debate and decision making more broadly.

And the example that I use in the book is Norway. When they discovered North Sea oil in the 1960’s they set up a pretty standard centralized state oil company, the kind I would be critiquing. That was their response to trying to have some sort of national public policy control over oil and not just allowing those nasty American multinationals just to come in and exploit their oil without any local benefit.

So they set up a state oil company, and it was a very conventional company, run by bureaucrats, and lead civil servants, people absconded in from private business.

But the other thing they did was they encased that oil company within various institutional structures and democratic process that meant that knowledge and awareness of the oil industry and how it works was shared through broader society. So the oil company, Statoil, was always having to report back to different committees of the parliament—not in a way that stifled its ability to operate efficiently, because the day to day control and the management of operations was still in the hands of the management. But nevertheless it had a requirement to report to all these different committees of the Norwegian Parliament. That meant, effectively, the goal setting happened through democratic government processes.

And the other thing they did, is they created another institution called the Petroleum Directorate, which was tasked with making itself knowledgeable about all the areas of research and development, about oil. So you had a kind of countervailing centers of power and knowledge I think, in that situation.

Germany does this quite well, if you look at the country as a whole in the sense that it doesn’t allow geographical concentration or decision making in one place, but it’s kind of scattered. They have the supreme, they have the federal court in one city, the financial sector’s in Frankfurt, the capital is now in Berlin. But there’s been a determined policy to spread national centers of decision-making power to different cities. So that kind of de-centering for me is just as important as decentralization.

Adam Simpson: That brings up an interesting question related to energy. And obviously the Norway example is a good transition here. I know you’ve been studying energy democracy and remunicipalization in various places. So given the imperatives of climate change and the intransigence of many traditional energy companies, maybe you could just speak a little bit more about public ownership in the energy sector on various places, I know in Scotland just this week the SNP proposed a national publicly owned energy company.

If you could talk a little more about that and maybe what you see are the greatest possibilities for advancement when it comes to public ownership or collective ownership within the energy sector.

Andrew Cumbers: I think this is some really exciting things happening around energy in Europe in particular, but also in the US where you’ve got a place like Boulder, Colorado. It’s a very uneven patchwork, though, in terms of what’s going on. You’ve got some places where you’ve clearly got radical groups mobilizing and agreeing, leftist alternative groups, mobilizing around community energy and doing some really interesting things. Often in rural areas actually because urban areas, big machine politics is bigger. I think that’s true of the US and probably European cities as well. In a way in a nice rural area of Vermont you can probably develop nice, easy models of energy democracy with less difficulty than you can in a city like Hamburg in Germany, which has got massive vested coal and trade union interests that are against taking things into public ownership, and indeed even against a postcarbon transition.

So I think the politics are very different around energy democracy in different places and different context. But nevertheless, there’s a lot of interesting things going on. In Germany, you’ve had this massive remunicipalization process where over 100 formerly privatized local energy and electricity utilities have been brought back into local public control. Germany has a very decentralized energy system, a bit like the US in some ways. So it’s been possible for, in particular cities, for movements to mobilize and reclaim these utilities for the public sector.

The biggest problem we have in the UK around energy and energy democracy is that we have a very centralized system, in the energy sector in particular. When the nationalized companies were deprivatized, basically created these national privatized oligopolies or monopolies. And the grid for example in the UK, the national electricity grid, is owned by a private company. One company that owns the whole grid. It’s very difficult to have local success stories in the UK where you can create fully integrated energy democracy systems.

So, what’s been happening in the UK is that cities are setting up their own electricity supply companies. There still operating off the same privatized grid, but under the UK system, anybody can set up an electricity company and supply customers. It’s still the same power, same source of power. But that has kind of encouraged or fueled, if you pardon the pun, an interesting attempt for the public sector to get back into the energy sector. But you’re quite constrained in the UK, without national government change and that’s what a Labour government would do differently. It would allow for re-nationalization of the whole grid and sector.

Whereas in Germany where you have much more decentralized grid systems, it’s been possible for a place like Hamburg, for campaigns that have basically reclaimed the whole of the energy system from privatization. And there’s an interesting mobilization around that.

Scotland announced a new public electricity company—but as I understand it at the moment it will only be an electricity supply company because the Scottish government doesn’t have the power to reverse privatization in Scotland. Energy does not devolve, it can only be done on the UK level. The only way you could get a fully integrated public energy company in Scotland was if you were able to create your own local grid. And that’s a massive undertaking of course.

So that’s, you know, there are a lot of constraints on energy democracy. People are very celebratory of it but I think some places it’s easier to do than others. And I think you need probably different solutions in different places. But at least in Scotland I think the public debate has shifted quite significantly. The party in power is the Scottish National Party, which is a kind of a middle of the road party that has very cleverly occupied the center ground. It claims the democratic aspirations when it suits it, but it also in the past has been advocating a kind of low-tax Celtic Tiger model of Scottish independence, a tax haven kind of model. And the previous head of the Scottish National Party, for a brief moment, was very favorable to Donald Trump, which probably tells you a little about the ambiguity of their whole project.

But nevertheless I think they felt the need to move to the left around public ownership in particular and around setting up a national investment bank. Partly this is because of the the broader shift to the left in the UK and the realization that public support for what used to be seen as radical outlandish solutions a few years ago, is now actually increasing and becoming more mainstream.

Adam Simpson: Thanks so much for sitting down today and talking about this. And thanks as well to Thomas for joining me today for this conversation.

For our listeners, we’ll see you next time on the Next System Podcast.

Andy thank you so much.

Andrew Cumbers: Thank you.

Thomas Hanna: Thank you.