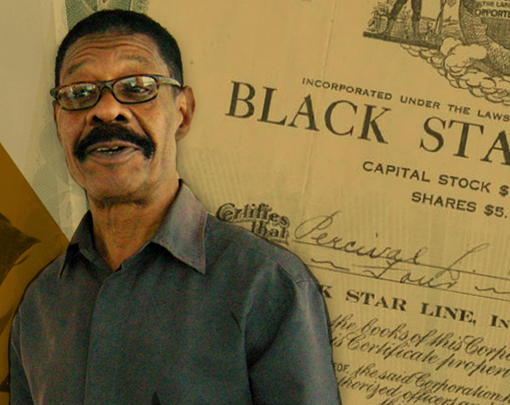

This week we’re talking with Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. The book focuses on how narratives have been constructed to explain the region’s poverty and how those narratives fail to serve Appalachia’s people.

Subscribe to the Next System Podcast via iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, or RSS.

Adam Simpson: You’re listening to the Next System Podcast. Today, we’re talking about the history of narratives, the radical movement history and the radical movement present of Appalachia, and we’ll do so by speaking with author Elizabeth Catte about her new book, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Elizabeth, welcome to the Next System Podcast.

Elizabeth Catte: Hey, it’s good to talk to you.

Adam Simpson: Thank you for being here. By way of further introduction, Elizabeth is a public historian with a PhD from Middle Tennessee State University whose work you can read at www.elizabethcatte.com. Her work has been featured in many places, but to name a few, I’ll say Belt Magazine, 100 Days in Appalachia, and one of my favorite podcasts, Trillbilly Worker’s Party. She’s also the director of Passel, a socially-conscious historical consulting firm. Elizabeth, that’s actually where I want to begin is just asking you to frame the notion of what it means to be a public historian as opposed to a historian and kind of a little bit about this organization, Passel, that you work at now.

Elizabeth Catte: Awesome, so fair warning that there is no consensus about what exactly a public historian is, and a lot of us think that that’s kind of the fun thing about it, but generally speaking, public historians are people who undergo slightly different training in the academy. Our objectives are to, as the title would suggest, work with the public to create better quality historical interpretations, help the public understand history outside of the classroom, so that’s the work that I do.

A lot of public historians end up in museums, or working for the National Park Service, or at historic sites, archives, libraries. There’s a wide variety of venues you’ll find public historians at. Some people are public historians and probably don’t even identify as such. The work that I do, I try to make history digestible, and readable, and vital to the public. I try to help communities utilize their history as an asset to understand their place in the world and the stories they want to tell.

That leads me to talking about Passel, which is the little historical consulting company that my partner and I direct. What we do there is we work primarily with community organizations in Appalachia. We want to help them interpret sort of suppressed or hidden or not visible history, so we work a lot with African-American community organizations, or organizations that interpret labor history, and we try to offer very affordable or free services to them to help them improve historical interpretation, so we can connect them with resources like grant writing, or we can do some of that work ourselves. We can network them to other institutions, like in the federal government, that might be able to help them as well.

Adam Simpson: That sounds great—very meaningful and important work. I do want to turn to your book, though. I really enjoyed reading this book, its critical reaction to the popular narratives that surround the region of Appalachia, and in particular, the final chapter that offers an alternative lens. I just want to begin by asking what was it that drove you to write What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, and what does this book mean to you?

Elizabeth Catte: I wrote the book because I was incredibly angry about a lot of things. Obviously, I was angry at the state of our politics. I was angry at the state of our narrative, both nationally and regionally within Appalachia. I was angry that yet another person, another wealthy, well-connected white man had emerged as a spokesperson of our region. If you read the book, one of the things that I talk about is how J. D. Vance, [author of Hillbilly Elegy] is never just J. D. Vance. He’s everyone who has ever come through the door that has been opened that makes it possible for a single person or a single voice to be emblematic of the region, to be the spokesperson for our misunderstood souls, so I’m angry at that kind of power.

I was angry at the fact that I had recently moved from Tennessee, where I’m from, with my partner to Texas. The place that we were living on the Gulf Coast, Beaumont, Texas, is a place of ongoing, extreme environmental crisis, and I was mad that all the people who had always told me, from the time that I was born to 20, 30 years old, that if you want to be ambitious, if you want to achieve things, you need to get out of Appalachia and go somewhere else, and so I had been slapped in the face with the reality that I always knew objectively to be true, that there is nowhere else you can go where you will not experience poverty, where you will not see racism, or you will not see people exploited, where you will not be under the thumb and under the dominion of powerful companies that political leaders value more than you and your life.

I channeled my anger into this book, which is a brief book, but uses a lot of Appalachian history to push back against 2016 presidential election narratives, but also against this deeper belief that there is just a certain kind of culture, or a certain defectiveness, or a certain innate quality amongst demographics that rationalize all the bad things that happen in our country.

Adam Simpson: One of the key themes of your book is the power of narratives—where their power comes from, and what effect they can have on politics, on economics, and on society. In particular, I wanted to focus on that through the lens of something that you discuss in the book, this trope of using pictures of poverty in the Appalachian region to showcase, in a way, the economic and social problems there. What role do you think these images play in popular conceptions of the region, and what do you think they mean to the people that reside there?

Elizabeth Catte: Oh, I mean it’s a huge deal. The visual archive of Appalachia is very specific, very enduring. What I like to ask people to do, which is almost the easiest thing to kind of get this conversation started, is to Google Appalachian photography (or use some other search engine, I don’t care!). Take a look at what you see and let that reality sit with you—because what you will likely see is images that are almost exclusively black-and-white, even though there’s diversity amongst photographers. We’re talking about photos from different time periods, but black-and-white is the kind of the visual theme to the collection of images presented. The subjects are going to be almost exclusively white. They’re going to be portraits. You’ll see people experiencing poverty and seeming to be suffering because of it.

There might be 20 or 30 different photographers who are the creators behind those images, but the output is almost identical, and that links to the way, I think, that the region started to be consumed and depicted during the War on Poverty in the 1960s when you had photographers and journalists coming to the region to create a narrative that there was a very unique and distressing form of white poverty in the country that had flown under the radar, and that the country (i.e. good, white, middle class people) needed to have its eyes opened and to be shocked into compassion. That narrative persists and exists within Appalachia.

If you looked at some of the articles that came out during the 2016 presidential election, they were almost identical to what I found in Life Magazine during the war on poverty. There was a Huffington Post essay, for example, that said, “This is the America that voted Donald Trump into office,” and there was pictures, black-and-white pictures, of dilapidated trailers, and bars, and older women at bars smoking cigarettes. Those visual stereotypes were very much in play, and it’s important to remember that almost every image that you see in a news article or in your Google search has made somebody some money. There’s lots of amateur photography and creative output, but generally speaking, to be one of the top Google results, to have your photographs featured in a prestige publication, you have made money off of that, and I’m not shy about saying that you have made money by recycling stereotypes.

Adam Simpson: Right, right. You mentioned that, generally, these pictures tend to depict white people, exclusively. There was this tendency, after the 2016 election, to talk about the white working class in different ways, but one of the threads in your book that came up that I thought was particularly interesting was that there’s kind of this pernicious explanation of the lack of economic development in Appalachia that focuses on this presumed shared Scotch-Irish heritage. I wanted to ask you, really, what do you make of the purpose of this argument?

Elizabeth Catte: I have a very specific criticism with the sort of fetishization and fascination with Scotch-Irish culture in Appalachia. The first thing we need to understand, it’s a real culture, sort of. It’s a specific kind of back-in-the-day Irish settler that came over to Scotland as a colonizer and then made their way to the United States. About 1 to 2% of the national population claims Scotch-Irish heritage. White people have been able to self-identify their ethnic heritage on the census for about 30 years, I think, and few other demographic statistic-collecting organizations monitor this as well, so we kind of know, in a general way, how many people say that they are part of this heritage, and it’s about 2% nationally, maybe about 2.2% in Appalachia. So I find it very kind of curious why this particular distillation of white heritage keeps coming up over and over again in modern conversations about Appalachia, particularly this fascination for understanding what “hillbilly culture” is, which is a phrase we get from Hillbilly Elegy.

To understand, I think, my belief why people are so fascinated with talking about Scotch-Irish culture, you have to go back quite a considerable way through a portal that is deep and dark and not pleasant at all, to understand how Appalachia became entangled with the modern eugenics movement. This is not a very pleasant history at all. The general arc of Appalachian history is that it is the story of poor people who have been living on very valuable land, and that’s a history that tracks through forced indigenous migration to things happening in 2018 in the West Virginia Senate about things like co-tenancy laws.

That’s the arc of our history, and the arc of our history is also the schemes that powerful people have used to try to sever us from the wealth of the land. One of the most enduring tactics is to say that the people have a deficiency in their culture, that they’re backwards, that they’re frozen in time, that we must make some kind of intervention in order to help them, help them progress, make them participants in the spirit of American progress. If we don’t, they might keep dragging our culture backwards, and so the exaggeration of Scotch-Irish heritage… Sometimes it’s Anglo-Saxon, sometimes they call it pioneer culture, but generally speaking, the conversation about hillbilly bloodlines, so to speak, has been one that’s been attached to unethical and dangerous schemes to get poor people away from the wealth of the land around them, to blame poverty on the people experiencing poverty, and not on the systemic problems that are ubiquitous throughout the country.

I could understand why somebody who doesn’t know much about Appalachia or know this history might kind of say, “Oh, you know, maybe that makes sense,” but what we also have to understand is that we’ve had hundreds of years of people in Appalachia and in the academy and in social sciences saying, “This is BS. This is bogus. There is no basis for this belief,” but yet it endures. In 2018, I’m super comfortable to say that if you are an intelligent person, if you have a Yale degree, for example, or if you make a name as an expert, then there is no way, shape, or form that you should be kind of spreading these falsehoods about the region unless you are really attached to what they do, and what they seem to do is make a case that poverty is just innate among some people in some demographics.

Adam Simpson: Right. This came up toward the end of your book, that it seems connected, in a way, to the concept you discussed about Appalachia as an “internal colony,” and it seems like a very complex and thorny issue—you wrote in your book that it was, at the same time, both a satisfying way to look at it and both deeply problematic.

Elizabeth Catte: Right, so a lot of people have had much to say about the idea that Appalachia is an internal resource colony within United States. To give this a historical dimension, we can say that the internal colony model developed in the 1970s when there were some pretty specific events happening in Appalachia, namely, there had just been a series of catastrophic floods in the region that were triggered by unethical practices by mining companies—strip mining and that kind of thing.

What happened is when organizations or individuals wanted to bring relief to the region, they had a really hard time finding land that wasn’t controlled by obstructive corporate entities, but also not damaged. This was such a huge dilemma—to have to look so hard to find land that is not controlled by an outside corporation—so this led to a land study, the Appalachian Land Study in 1980 and 1981, and within that, people who were trying to think about ways that they could discuss the region and its problems holistically really seized on the idea of the internal colony model to explain the way that wealth and power worked in Appalachia.

It was tied to the politics of the time, the left’s anti-colonial sentiment, and it also matched what powerful people thought about Appalachia. It is problematic, but let’s also acknowledge that people with power and wealth looked at Appalachia as a colony. When they talked about Appalachia, they made comparisons to countries in Africa. They said, “Oh, you know, the mountains, the jungle, same thing.” Even when they wanted to bring philanthropy to the region, what they were saying was things like, “Well, you know, if we’re helping newly liberated countries in Africa escape from the colonial past, why can’t we help Appalachia too?” There’s this language of colonialism that surrounds Appalachia that’s very much top-down as well.

Like you said, it’s problematic and thorny for a lot of reasons, namely because it gives us no real way to talk about the history of forced indigenous migration in Appalachia. It doesn’t give us a really good way to talk about the way that racism and homophobia and things like that have roots in Appalachia rather than being imported to the region by outsiders. These are the things that we need to be cautious of, but it also helped a lot of people, like me, think about power as opposed to always needing to push back against stereotypes, and talk about reality of Appalachia. It helped me kind of attach what I wanted to say to the way that power worked.

Adam Simpson: Sure, sure. J.D. Vance, his book, Hillbilly Elegy, it’s in a certain tradition of narratives about Appalachia. I can’t remember the author’s name that you discuss in your book who wrote Night Comes to the Cumberlands, I believe it’s called…

Elizabeth Catte: That’s Harry Caudill.

Adam Simpson: Right, Harry Caudill. I know that, during the Great Depression, there were these efforts to kind of construct maybe what you could call public history as part of the job program during the Great Depression. What’s the legacy of this history of constructing narratives for Appalachia? How does J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy fits within that framework?

Elizabeth Catte: Just to be clear, Appalachians aren’t the only people or only demographic that suffers from this problem, but we do have a tendency to have our history and our stories told by an explainer-in-chief. As you mentioned and as I discussed in my book, before J.D. Vance, there was Harry Caudill. Before that, we had photographers and people like Sherman Mandel who were doing sociological studies of the region like Hollow Folk, the story of the Shenandoah Valley residents.

We have a problem in Appalachia that people are very comfortable seeing and understanding Appalachia through only one set of eyes or one perspective. Of course, we have some powerful photographers like Shelby Lee Adams, for example, that do visually what these literary spokespeople are doing, and that really, really irritates me. I think it’s hugely unfair. It’s one of the things that drove me away from Appalachian studies. I’m a historian, but I studied primarily African-American history and public history, and I would pick up books about Appalachian studies on the side, but I always assumed that if—and it was not right for me to think this!—that if I did Appalachian studies, I would have to read these awful books, that this is just how Appalachian studies was constituted. Again, that was not a fair thought for me to have, but this is what happens when your narrative is so strongly attached to the viewpoints of only a small cadre of people.

Appalachian narratives tend to be, in my opinion, often narratives of omission. There are things that the narratives say, but there’s so much that they don’t say. One of the things that I hear over and over again when people come and talk to me about my book is that, “I feel seen.” I’m so happy to do that, but I also think that it is so sad that there are so few books that have entered the mainstream that people can go and get that same experience.

Obviously, I’m going to acknowledge to the end of days that there is a rich Appalachian studies bibliography in the world, that there are thousands and thousands of books, great books about Appalachia studies, but the ones that the media like, the ones that the public like, the ones that accrue wealth for their authors, tend to be these really kind of pitiful stereotypical culture of poverty offerings. Obviously, what I do is I want to think about why that is, and I want to change it.

Adam Simpson: Right, right. My sense, as an outsider, reading your book is that it there must be some sense of being trapped between people on the right, like J.D. Vance, who say that all of this is because of poor choices and then, on the other hand, you have liberals who complain that these people keep voting against their own interests, which seems to be more or less the same critique. Does getting over this apparent disdain for the region demand a more systemic critique involving the forces of capitalism and environmental degradation?

Elizabeth Catte: Yeah. We don’t have many fans on either side of the political aisle, it seems, and especially lately. I’ll use the example of the teachers’ strike in West Virginia that just happened. It does feel like we’re caught in the extremes of the narrative. I describe it as a pendulum that swings back and forth where Appalachians are either heroes or they’re heretics. There’s nothing much in between.

Think about the 2016 presidential election narratives, think about Trump Country pieces, think about all the political analysis that presented Appalachians as prone to this kind of political self harm, that they were complacent, that they were voting against their own interests, this, and that, and the other, and compare that to some of the things that we’ve seen attached to the teachers’ strike where Appalachia is engaged, politically active. They’re poised to lead this broader movement that could really be transformative in politics, and so now we’re like, “I guess people want to hang out with us now.” It’s really weird because nothing—and I mean nothing—has fundamentally changed in the region, and nothing had fundamentally changed in 2016.

It’s really interesting to me that liberals like us now, maybe, so what I see is a lot of people in the region, and me included, using that opening to say, “Well, you understand that Democrats did this to the region, right? That both parties have had their hands in the economic decline and systemic kind of degradation of Appalachia.” We can go ten years down the road, and we can point to a specific point in West Virginia politics when the state was controlled by Democrats—because it was controlled by Democrats, for 80 years—when these corporate tax cuts were instituted that set the West Virginia economy going down this road that resulted in not having the budget, or so they claimed, to pay teachers adequately.

Liberals feel like they’re back in the fold now, but we’re like, “Ah, ah, ah, not so fast.” Now it’s time to have those conversations that you didn’t want to have in 2016 about how there is good reason to feel alienation from both parties, and we have to kind of have a come to Jesus moment about what brought us to this point, good and bad.

Adam Simpson: Right. Well, about the West Virginia teachers’ strike, I’m certain that most people ought to know the very radical labor history of Appalachia. How do the writers in the more conservative and cultural focused tradition we were talking about earlier deal with this notion that there is class struggle going on in this region?

Elizabeth Catte: That’s really interesting. J.D. Vance…he doesn’t have a narrative of class struggle. He has a narrative of class, which is very, very different. One of the reasons that he likes the narrative of class is because it lets him discard race. I mean he says this explicitly. He says it explicitly in the introduction. He’s like, “Well, let’s set aside this racial prism and look at how poverty affects people through this lens of class,” so this makes people like white liberals, for example, that are very fatigued of making everything about race go like, “Oh, yeah! Hurrah! We’re not going to have to talk about these like sticky, uncomfortable topics anymore.”

Other people that have filtered through the region as spokespeople, it’s complicated. Harry Caudill, for example, was a little bit different because he actually did experience some of the effects of this suppression and exploitation along with his neighbors, because he was a resident of eastern Kentucky, which had horrific problems with strip mining at the time. I think the point that I could probably make to tie this together is that people who emerge as spokespeople of Appalachia tend to be, excuse me, people who can be of Appalachia in some way but also above Appalachia, and that has a lot to do with class.

I don’t think it’s immaterial that both Harry Caudill and J.D. Vance are lawyers by training, for example, so they have this [position of privilege] For Caudill, it was a middle class profession. For J.D. Vance, I don’t even know if we have a word to describe the level of venture capitalist kind of stuff that he’s involved in. It was an idea that they had transcended, transcended their backgrounds, and now they could be trusted to talk objectively about the people left behind.

Adam Simpson: When I began talking about the kind of radical history in the region, I was wondering … well, you mentioned the pendulum tends to swing both ways. I feel like I’ve seen that with the West Virginia teachers’ strike recently because it … You have a statewide strike, which was very, I think, exciting for a lot of people on the left and even for a lot of liberals, and then once the deal has been made and the … I think I immediately saw an article that was like the teachers get their raise, but at what cost?

Elizabeth Catte: I think I wrote that article.

Adam Simpson: Did you? Oh!

Elizabeth Catte: Yeah. I wrote that article for The Nation, and I think it had almost the identical take—of course the context was different—as Sarah Jones, who wrote something similar for The New Republic. It’s important to know that we’re both from the region. It’s not about diminishing the power of the teachers’ strike or being pessimistic about the movement that has grown. It’s not about being glum about what teachers have achieved, but it is about acknowledging the real truth that all the evil people that were in the West Virginia legislature are still there.

It is their priority to find a way to save face in a big way. They’ve been knocked off their pedestal just a little bit by this very populist movement that doesn’t have, really, a certain political affiliation. There are Trump voters, Clinton voters, non-voters in the mix. What many wanted to see happen, and what they were connecting it to, is this larger tension in West Virginia and the region about who is most important to the state. Is it people who kind of carry forward this vision of the common good like teachers? I think they’re really emblematic of that, a shrinking common good. Or is it wealthy investors who would gamble away our future prosperity on [tax breaks] and often lose. They’re thinking ”if we give them enough tax breaks and room to reinvent the region that they’ll reward us with new investments!”—and that hardly ever has worked out.

We’ll see some backlash to what the teachers achieved, for sure, and one of the ways, historically, even outside of Appalachia that this has been achieved is politicians pitting workers against workers, so we’re pitting the poor against poor. There are ideas in place, particularly among the state’s Republicans to make up the budget deficit that will be transformed into the teachers’ salary raise from programs like the state fund for Medicaid assistance, or tourism, or community college tuition assistance, or social service programs, and so that might be coming down the pipeline. It’s important to acknowledge that, in my opinion, up front, so we’re prepared for what’s to come because 2018 is an important election year in West Virginia and the rest of the country. There are a lot of politicians very, very intimidated right now in the state, and they’re going to come out swinging against people who have threatened their position.

Adam Simpson: Absolutely. I think it connects to the next question I wanted to ask, which is about power, and how this relates to capital and the extractive economy, in particular with coal.

Elizabeth Catte: One of the things that was particularly frustrating for me about the narratives that emerged, in the 2016 presidential election and beyond, was the idea that coal is dead. Donald Trump was going out with this rhetoric that said, “We’re going to being coal back, clean coal, beautiful coal,” and there’s an endless stream of, particularly liberals, dunking on that saying, “Look, ha, ha, ha, coal is dead. Wise up Appalachia,” this, that, and the other. It is absolutely true that the functional end of coal is coming in our lifetime, but there’s also some evidence that we’re going to get coal 2.0, which would be the natural gas industry, particularly in West Virginia and the Ohio Valley, and in Pennsylvania too. They’re fracking hubs.

All of the people who do their kind of evil machinations attached to the coal industry, they’re attached to the natural gas industry too. It’s half a dozen of one, six of the other, for them where they get their money from. Of course, they’re sad that they’re going to probably have to shut down the coal mines, but they’ve got a pipeline project in development, so nobody’s going out of business. Nobody’s losing their family fortune. Nobody’s getting voted out of office. Our reality, in terms of the extractive industry, is it’s going to be sustainable because now we have industry leaders, and again, particularly in West Virginia, that want to turn Appalachia into a natural gas hub.

You’re from Texas. You know Beaumont and Port Arthur and all those places, and you know that it’s a natural gas hub, but you also know it’s very close to the coast, and we’ve had lots of environmental catastrophes with hurricanes, leaks, oil spills threatening oil production, so why not move them inland? This is kind of the ideas that are floating around to transform Appalachia into a Gulf Coast 2.0 to use it as a center of a pipeline hub.

When people say, “Oh, coal is dead. Invest in clean energy. Make plans for the future. Learn to code,” it really doesn’t accommodate the reality that we’re still dealing with the same people here. We’re dealing with another source of energy, but all of the same problems have a very high risk of staying with the region for another century, and so, again, there’s a chance that our reality won’t shift, and there’s also all the environmental degradation that has come parallel to the coal industry, such as pollution, acid run off, this, that, and the other. We have horrible health outcomes in parts of Appalachia. We’re still going to be dealing with those realities for a long time to come too. We have laws in place that spell out some responsibilities that energy companies have to the environment, that there’s no strong mechanism to hold them accountable.

We’re in a tough situation regardless of whether or not the coal industry packed up tomorrow. We’d still be in a really, really hard place. I mean Rick Perry said recently something like, “Oh, I think, you know, we have a potential to make Appalachia a hub for the extraction industry,” and it was like, holy cow, really? Wow, big if true, Rick Perry. There’s a big risk that there’s just going to be a continuation of the same thing, just a different outlook.

Adam Simpson: Yeah. I also read recently that black lung has had basically had a huge resurgence that, if coal were dead, I assume we wouldn’t be seeing such trends, that it’s still having an effect on people.

Elizabeth Catte: Yeah. The black lung resurgence is kind of complicated. There’s a lot of stuff going on in the background with that. There’s not only the environmental reasons that people are getting black lung and getting black lung younger. There’s this whole story about labor corruption in the background, about doctors who were contracted by the Department of Labor to study black lung and to help diagnose black lung and to make occupational health and safety recommendations, kind of just siphoning money away for the government to enrich themselves, so it is hugely messy.

It’s absolutely true that if people didn’t work in mines they wouldn’t have black lung, but black lung is just one specific occupational illness. We still have people in Appalachia who are very ill from the way that their water has become contaminated from chemical, and mining extraction, and things of that nature, so we’re not going to be a healthy region anytime soon.

Adam Simpson: Well, that’s a rather somber note toward the end of the podcast. Is there anything that we haven’t mentioned or haven’t discussed yet that you think you’d want to share with our listeners before we conclude today?

Elizabeth Catte: Yeah. My final thought is think hard about how our different regions are connected. You and I have talked about so many in this short conversation already, you as a Texan, me as an Appalachian, and things that we have in common and the way that industry, and labor, and politics flow through our regions. If anybody wants to know more about Appalachia, by all means, read, learn, experience, but also look at the things that are going on in your region as well, the way that the power is imbalanced and wealth is imbalanced. Chances are, the things that you have experienced in your backyard are in my backyard too.

Adam Simpson: Right. Yeah, when you expressed that when you went to Beaumont and there were still poverty and things like that, I got a sense that maybe if you’re going to experience environmental degradation, and you’re going to have to see poverty, better to do it at home. Is that just about correct?

Elizabeth Catte: Yeah. I mean one of the things that was crazy to me in Beaumont is people who were business leaders at the university or well-to-do kind of middle class people, they were like, “Oh, it sounds like you have a really hard time in Appalachia with the coal industry, and there’s a lot of poverty there,” and I’m looking across the street at a poor African-American neighborhood that was strategically placed 500 yards from an oil refinery, and I think how are our problems different from one another? How are our problems different? Resist the impulse to indulge in escapism when you look at the problems of Appalachia. Possibly, you’re looking at the problems of Appalachia because you don’t want to see them in your own backyard.

Adam Simpson: Absolutely. Well, Elizabeth, well, thank you so much for joining us today. I’ll say again to our listeners do check out this book, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, by Elizabeth Catte. Yeah, once again, Elizabeth, thanks so much.

Elizabeth Catte: Okay. Thank you for having me.

Adam Simpson: Absolutely.