This week Nishani Frazier sits down to discuss her book Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality and the Rise of Black Power Populism. Nishani is a fellow at The Democracy Collaborative and an Associate Professor at Miami University of Ohio. You can learn more about the project at https://harambeecity.lib.miamioh.edu/.

Subscribe to the Next System Podcast via iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, or RSS.

Adam Simpson: Welcome back to the Next System Podcast. I’m your host, Adam Simpson. Today, our guest is Dr. Nishani Frazier. Nishani is a new fellow at the Democracy Collaborative and an associate professor of history at Miami University of Ohio. Her research interests include 1960s Freedom Movements, oral history, food, digital humanities, and black economic development. Nishani’s recent book publication, Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism was released with an accompanying website, also titled Harambee City. Without further ado, Nishani, welcome to the podcast.

Nishani Frazier: I’m very pleased to be here. I’m excited to be a part of a group that’s actually interested in thinking about how we can create the city in which every person and everybody both serve and be a part of, so I’m excited about that.

Adam Simpson: Absolutely. My first question: The project of Harambee City—and perhaps even the Congress of Racial Equality more broadly—are not historical precedents that all of our listeners will be aware of. While obviously I would refer our listeners to your book for the full story, how would you describe Harambee City to someone hearing about it for the first time?

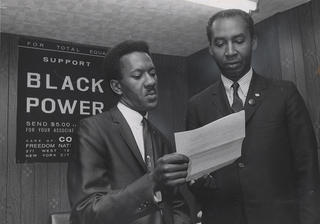

Nishani Frazier: Sure. This is what we call the elevator pitch. Effectively, my book traces the rise of Black Power within the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and it focuses in particular on the emergence of the Cleveland chapter as playing a central role in that rise in Black Power. The books begins with the origins of CORE and it questions the idea that CORE started off as a non-violent, direct-action organization. It’s actually a lot more complicated than that. As CORE developed toward Black Power in the latter 1960s, it takes a turn toward economic development as their approach to Black Power, which is unique compared to other civil rights organizations.

The [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] (NAACP) continued to focus on our legal presence; [The Southern Christian Leadership Conference] (SCLC) was mostly a Christian-based, religious-based organization, continued to do protests. [The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] (SNCC) actually turned fully toward Black Power, but began to decline in that same period. CORE was also in decline, but it was searching for new avenues by which to survive as an organization and continue uplift of the Black community, moving from integration to this idea of community organization and uplift and economic development.

Adam Simpson: There’s an interesting tension in the book, around this notion of economic development as a pathway to Black Power, juxtaposed, in particular in the 1970s, with this Nixonian version of Black capitalism. How do you separate these two concepts?

Nishani Frazier: CORE got in a lot trouble for this one. Part of it was because members of CORE had actually met with campaign members and persons associated with the Nixon administration and had talked about economic development; however, what CORE was explaining and what the Nixon administration campaign heard as ‘Black capitalism’, there were two different things going on. Black capitalism effectively mirrored American capitalism, just in Black, right? The same labor relationship of owner versus labor, that remained intact.

The only difference was that there was a Black owner. It was presumed that this was still helpful to the Black community, because if you had Black owners, they would be more inclined to hire Black laborers, and they would be more inclined to serve the Black community in which their businesses operated. There was an assumption that there would be some sort of philanthropic element to Black capitalism along with building Black wealth. The problem with that, of course, and many people pointed this out, was that it was individual.

You’d have one individual owner, and laborers—especially if they were low-income laborers—would remain in place. The problem with that is that that didn’t break the back of the poverty and the economic inequality that African-Americans literally had dealt with from slavery up and to the 1970s. CORE was actually offering something else. It was offering what they termed a kind of group ownership in the form of economic development. That took multiple forms. The first one had to do with who was going to own a business.

If you had a business, for example, a McDonald’s, the laborers would serve as owners of the McDonald’s. The manager would have a larger portion of ownership, but if you were a cashier, if you were fry cook, whatever you were doing in McDonald’s, you would have some sort of ownership. The intent was to move you from one income, which is the wage labor income, to a second level of income having to do with ownership. The idea was that that would give you access to capital instruments, right? You would move beyond this notion of the one person who owns it.

The other thing is that you could have a group of people in the community who could also have part ownership in the business through some form of stock. What was interesting about CORE’s approach was that it wasn’t something that you had to pay for alone. Like some people, if you could afford it, you could certainly pay, but if you didn’t have the money, you could use ‘sweat equity.’ That means you do some sort of work on behalf of the organization, or the business, that would contribute toward your stock ownership.

The whole point was that you would not have concentrated power and concentrated wealth in the individual. You’d have it among the community and the group, and then hopefully by extension, that would then allow for the whole community to begin to emerge out of poverty. This is not a quick process, obviously. Nobody was going to be filthy rich, once they got ownership in a McDonald’s. The hope was that you could start through some path to break through this poverty; break through this bottom that African-Americans were confined to in terms of economic and financial well-being.

Adam Simpson: I recently attended a symposium that was connected to a group called ‘The New Abolitionism’, which is about rethinking monetary policy, and in particular as it relates to Black economic power and inclusion in the economy. One of the speakers pointed out that a dollar in the Asian community stays there for 28 days. In the Jewish community, a dollar will stay there for 19 days, but a dollar spent in the African-American community, tends to stay there only six hours before diverted to some other part of the economy. The speakers were advocating for, in addition to banking with Black-owned banks, advocating for Black economic power in the sense of creating these communities where the dollar would stay there. Is that, in your mind, connected to this notion of a traditional business owned by an African-American versus other economic models or firms within the economy? Does that make sense?

Nishani Frazier: Yes. In fact, it’s interesting that you noted that because part of CORE’s approach to economic development, of course, is that we’re talking about broad community development that would allow for the money to circulate for a longer period of time, compared to the normal experiences of African-Americans when the money goes straight out. If you take the Target City Project that CORE had in mind, what they initially envisioned was housing, a shopping center, an export business for Africa, electronic business where they would import TVs from Japan, which to me, is probably the most fantastic thing, right? The 1960s, they’re talking about Japanese TVs.

This is all normal now, but this is something that’s unique at the moment. All of it is designed to create a kind of economic structure that would allow the community to purchase within this framework. Purchase a home, purchase their food, purchase their businesses, and it all would circulate within the community.

Of course a lot of people had a lot of fear, particularly in the Nixon Administration on the conservative side, about the nature of such a financial economic space, because their fear was that it would lead to not just a financial empowerment of the community, but it would serve as a mini-municipality where things like how the community is run, services, things like that—that at some point it could possibly challenge outside businesses from being able to come in and develop in areas. They were afraid it would mess with free market competition and things like that.

But the whole idea of economic development was that you would be circulating the funds throughout the Black community for quite a bit before it would go outside of that community. As one of the critiques was that that program or that project would not necessarily last very long because the moment that money started to circulate within the Black community, economic competition from the outside would likely want to have a piece of the pie, as you will. That would disrupt this whole process of circulating money.

That’s not necessarily a far-fetched criticism. A member of CORE on the west coast later developed African-American dolls and the people in the community, particularly women who had been in the welfare system, went to work for this doll company. They had Tamu, they had celebrity dolls. They had produced the first African-American dolls with all the African-American features and things like that. Mattel took one look at that and thought, “Oh! Turns out Black people like dolls and toys. We should do something like that.”

Mattel honed in on their business and of course they did not change the features of their [white] doll. They just sort of dipped it in a brown color and then all of a sudden, you had the Black doll. There is absolutely the problem and the potential of outside forces coming in, but I do think that there’s something about creating a kind of … I don’t want to say a ‘protective space’, but a space where you have the potential for money to fluidly move throughout the community before someone is coming in to snatch it.

Adam Simpson: You mentioned that this got CORE in a lot of trouble in the 1970s, but it’s apparent when reading your book that this controversy was very much personal in your life and your family. I want you to feel free to express your own story here, but also what was that kind of conflict like within CORE about which direction the group should be moving and what the priorities should be?

Nishani Frazier: Part of my approach to the study of CORE actually comes from my personal experience. My mother was a member of CORE in Cleveland, Ohio and then she later joined the Hough Area Development Corporation, which is an organization that was filled with CORE members and was one of the most well-funded organizations from Lyndon Johnson’s OEO Office, Office of Economic Opportunity. They funded a number of community development corporations. She later on in North Carolina worked to establish the Southeast Raleigh Community Development Corporation.

She took a good portion of the ideas from CORE and the HADC into her for economic development and that included housing, day care, looking at exports and creating economic relationships with African countries. It was a very complicated process. It got particularly complicated when in an effort to obtain funding, she would go to various foundations. Then she also had to go to the state of North Carolina. They also provided funding for CDCs. This is where CORE also kind of got caught up is that, for a lot of people, going to these outside parties in the form of the Ford Foundation for CORE, or any of the other organizations, there was this fear that these organizations were more inclined towards Black capitalism and that their influence would be undone.

It would disrupt CORE’s really more radical approach to financial uplift in the Black community. That’s where the fear came in. There was a lot of internal conflict between CORE and its local chapters with regard to this whole question of where they got their money and the expectations. This turned really sour when CORE decided to go to the Nixon Administration. That was a no-go for many people within CORE. Their fear and their issue was that this was a person who had won by the “Southern strategy” where you appealed to segregationists of the South, using this language of “law and order” as a back-handed commentary on protests in the streets as a tool to obtain the presidency.

Setting aside racist comments, setting aside his election in terms of this administration, all of these things made the Nixon Administration a no-go. Persona non grata. You don’t go to them for nothing. CORE’s position was we’re going to anybody and everybody who’s going to give us the money to do what we want to do in the form of economic development. It didn’t always play out that the intention of the money giver would translate into their own mission or goals for that money. CORE had its own mission and goals and often it was the exact opposite than the money giver.

It played out, for example, in the Nixon Administration, CORE is pushing this idea of economic development; the Nixon Administration is pushing this idea of Black capitalism. They moved to create a bill called the ‘Community Self Determination Act.‘ This bill never gets the support of the Nixon Administration, but it does circulate in the White House, and among both liberal and conservative policymakers. The bill effectively was a national attempt to create a community development structure. This was going to be a meta, mega-structure for community development corporations that would take money from the federal government and then try to funnel this down to various communities to then create this idea of group ownership or community ownership.

This concept and this idea, for a lot of people, they just could not understand it as broad wealth ownership because in their mind was Richard Nixon, Black capitalism, and you’re going to Richard Nixon. In the book what I say is there’s this moment in The Cosby Show where they reflect upon this character who was brought to them in a really kind of funky way. They noted that the character may be the embodiment of steak and potatoes, right? The greatest thing you’ve ever had. If you serve it on fine China, that’s great. It’s even better, right? But if you serve it on a trash can lid, nobody’s going to eat it.

The Nixon Administration was the trash can lid, and the steak and potatoes was economic development and this community development corporation idea, but nobody was going to eat that. Nobody was going to accept that as long as the Nixon Administration was tied to it. It created a lot of conflict. Some chapters broke off over this issue of going to the Administration. It wasn’t just the Nixon Administration. They broke off also as a result of getting money from the Ford Foundation. There are a lot of people who just felt like CORE was acting as the middle man for Black capitalism.

Adam Simpson: The way you were describing Nixon in that particular moment seems very familiar at this particular moment. I wanted to ask, you had a recent piece in Truthout discussing some new Black mayors today. You were discussing kind of a more generally this concept of a radical city. I wanted to ask first how you might define what a radical city or even community. What are the components in your mind of that? Also, what do you think for people that are trying to articulate such a vision, what do you think they might learn from Harambee City and CORE’s project?

Nishani Frazier: Well, I was really excited to see all of these mayors. I want to be very clear when I talk about the rise of the Black mayors. There are many Black mayors. What I’m referring to when I say “Black mayors” are a certain group that have an affinity towards 1970s rhetoric, in terms of the focus on the Black community, in terms of language related to economic development, around housing inequality issues. If you look at places like Atlanta, on the other hand, a good portion of the conversation about housing insecurity, that’s coming from the community, that’s not coming from the Mayor’s office, which is still associated with the process of gentrification.

So there’s a distinction I want to be clear in making when I say the rise of Black mayors. I’m talking about a particular kind of Black mayor. Some of that has embodied by Ras Baraka and Chokwe [Antar] Lumumba in Jackson, Mississippi. He’s the one, of course, who coined the idea of a radical city. I thought the concept was really exciting and I was fascinated by this return, if you will, to kind of a 1970s milieu when it comes to how do we build a city? How do we create a city? We certainly have a history of that. You have Soul City in North Carolina. This is this Utopic city that was supposed to Black-led, interracial, that was going to have businesses and be technologically advanced and have housing, right?

There was, to me, this great affinity that I could see between 1970s Black activism and the language that you hear coming from some of the current Black mayors and some of the mayoral candidates. Unfortunately, a couple of my people lost. I was disappointed. It does beg the question how will these issues be resolved. I like the idea of the radical city as a concept, but I think that each space is going to different in what constitutes a radical city. I think there are some general things that we can say about what constitutes a radical city. When you have a city where only rich people can live, that is not a radical city.

Any city that is designed to prevent people from keeping up with the expenses around housing, any city where you can’t access food—and healthy food, certainly doesn’t fall within what I would consider to be a radical city. I can probably say what isn’t a radical city more than what constitutes a radical city. If I were to say what is my Utopian vision of a radical city, what I would hope is something that is environmentally sustainable and is inclusive of various economic levels.

It is not my intention to run the rich people out, but to insist that in creating a space for wealth in the city, that it doesn’t have to exclude everybody else in that process. In a radical city, everybody has got to share in that wealth and I mean wealth in a broad sense. I don’t mean just money. I mean like city services. Same trash pick up in this neighborhood, I should be getting in that neighborhood. Same educational opportunities in this neighborhood, I want in that neighborhood. A radical city should seek to aggressively create equal circumstances, regardless of your economic background.

Chokwe Lumumba, it seems, has really embraced this idea of environmental sustainability, more so than even Ras Baraka. There was a new study that came out about the economic impact of climate change in the South. One of the things they immediately said was that you can expect higher expenses around health and health services. With the kind of heat in those places, they’re expected to have more high blood pressure, heart attacks, all these kinds of things.

To me, that seemed to present a moment that Chokwe Lumumba could step in in terms of focusing on health and hospitals. Hospitals provide both jobs, but they also provide services to communities that could fit to and speak to the potential issues that we expect to see around climate change. Things like considering what elder care is going to look like, because those are most of the folks are be most affected by climate change. Thinking about how to give services that is not dependent on money exchange. If we talk about the use of solar panels, those are really big. Solar farms are huge in North Carolina now.

As much as Duke has been dumping its coal ash and doing all these other things, even they know the writing is on the wall and they’ve been surreptitiously and not so surreptitiously purchasing wide tracks of land and investing in solar farming as an alternative and electric source. I think that’s something, again, that he could also plug into providing jobs around green technology and then again, the sustainability. I think a radical city can talk about creating an equal relationship among its citizens where we’re all considered citizens and then being environmentally considerate and it doesn’t have to work in a negative way. You can do some things with it.

Adam Simpson: What would you say to people who are trying to articulate and trying to imagine a radical city? What do you think that they could learn specifically from Harambee City and the CORE Project?

Nishani Frazier: One of the things that I think is best to learn are what things that succeed, but even better, the best, is what fails? Here’s the problem. When it comes to funding sources, all of these funding sources run out. Whenever you create any of these businesses or you do any of these projects, at some point, you’ve got to figure out a way to pivot so that it is generating enough income for itself and whatever business it is, so that you don’t have to go through the Ford Foundation or to the state or federal government to continue to feed the organization and its operation—and it works the same way for a radical city.

Cleveland had Carl Stokes, and he depended greatly on federal funds for the Cleveland: Now! project, and that was really important. The problem of course, is that federal funds are not infinite. They will go up and down—and so the question is: how to create a sustainable institution and organization that will help bring the community toward economic uplift while not being dependent on external funding? That is a key problem to look for. I didn’t get a chance to talk about that in the article, but that would be one thing to think about with regard with to Harambee. I think that was why the economic broad wealth idea was so appealing to me, because the organization could invest in businesses, and that would also serve as income for the organization.

It wasn’t always going to be funds that they had to go after. I think the other thing is institutionalizing these ideas and this was something I briefly mentioned in the article. With the case of Coleman Young in Detroit, he’d done a lot of work to try and move Detroit toward some sort of financial stability working with different businesses and things like that. But you have to get it in the head of the businesses and companies that are coming in that they have to then be in a part of a circular relationship where they are feeding back into the city.

That’s what I mean by institutionalized. You can’t just sort of bring these companies in and say, “Okay, finally we’ve stabilized the city.” The problem is those companies can go anytime that they want to. They have to learn to be, what are they called … Citizen companies, right? You have to learn to be a citizen of the city, and their expectations that come along with your being a citizen of the city. How many jobs are you providing for working-class people, poor people? How are you helping to provide training and education for those who are on the lower levels to move them up to middle management?

You have to move these people away from profit-driven modalities, profit-driven sensibility to being part of a broader community. Then you’ve got to think about developing, and I think this is one thing was successful, developing the city as a whole. I think that’s probably one of my criticisms of Ras Baraka is that he started off with the city and getting in companies and businesses that helped to provide funding tax based for the city. These kinds of approaches should be done equally with surrounding communities and neighborhoods, because if you don’t do them at the same time, what happens is that the city builds up, people come, and they think, “Oh, the city’s gotten nice. I’ll come into the city.”

Then you have the process where people are now pushing into the city and developers are looking at this interest, and they’re looking at who’s around that they can push out. You have then, an uneven development in which the city is fine, but all the poor folks, the working class folks, they still don’t access to jobs. They still don’t have education and now they’re being pushed out because the city is now a city we all want to live in. You’ve done the great job of creating this fantastic city and so many people love it, they want the rest of you people to get out.

They’ve got to do this in a way that allows for a kind of equal balance of development. Otherwise, displacement happens, and it’s happening in Detroit. Coleman Young complained about Negro removal, that his father has fought for all of this development of the city, and it’s slow, but it’s moving. In the process, the interest that Detroit has generated has now led to more of a pushing out of those folks who are working class and poor and purchasing homes that could be renovated for someone who’s working class, but now they’re being taking over by developers.

If I were to say three things and sort of summarize: one, the failure of CORE was its inability to institutionalize. They tried to do that through the Community Self Determination Act, but wasn’t able to do so. Second, that you want to be able to be economically independent from outside sources, so that if a company just picks up and leaves, all of a sudden, the city is undone. Then finally, I think one of things that CORE did right was to think about how to build a city as a whole, not as a part. Not about companies and how much tax you can get, but how the whole of the city can survive and be effective.

Adam Simpson: Right. In the Truthout article, just moments ago, you were talking about how leaders like Ras Baraka and Chokwe Antar Lumumba, and what sets them apart from other mayors and from “the Obama era and neoliberal post-racial orthodoxy about municipal development.” In your analysis of the current system and why it’s failing, how did that neoliberal order fail to provide economic development, in particular for Black Americans and other marginalized communities? Both at the city level, and more generally?

Nishani Frazier: Right. I can tell you looking at Newark as a prime example, the previous mayor, Cory Booker had gotten a great reputation for being willing to work with the business community. I think anytime you start having a conversation with the business community in that way, that’s a conversation by its very nature that doesn’t include city residents. Those are folks who always assert this notion that they’re about building up the city broadly and if I build up the city broadly, it helps everybody.

It will all magically appear and make improvements for all in this one fell swoop. That’s this neoliberal notion where you don’t have to think about focusing projects and programs on systematic inequality. There are systematic financial process where people are locked at the bottom, and these won’t magically disappear if you work with the business community. That’s how I’ve seen this neoliberal Black mayor play out, where they’re playing the financial business game without speaking directly to the community and that’s different from say, Baraka and Lumumba.

Adam Simpson: Right. It’s funny, it sounds very much like trickle down economics, which most Democrats would immediately distance themselves from that phrase, but that’s exactly what your characterization leads me to believe.

Nishani Frazier: Right and I think there’s an insistence on not dealing with race, right? That this is not something that is a race issue, it’s just economic. It’s this claim that if you can create an economic layer of prosperity at the top, this will come down to the bottom—but it ignores the systematic way in which racism and discrimination has acted to leave behind and lock out.

You’re first left behind and then locked out from the whole city space and structure. I think that it’s inherently dishonest to have this conversation as if race has been irrelevant to how it is that Black community has gotten in the position that it’s in when you talk about places like Detroit and Cleveland and Newark, which is why I find the new mayors to be distinctive in that they’re very clear about grappling with that issue.

Adam Simpson: Right. I want to ask also about the issue of trade. In your book, you’re talking about Black populism. The conversations about trade during the previous election cycle, trade was referred to as a populist issue that was focused on by Trump, and it was focused on by Bernie Sanders. First of all, the phrase ‘populism’ was kind of dismissed as this negative thing, but it occurs to me in your book that CORE had thought about trade and had a plan for making trade work for the local community. I was hoping you might be able to elaborate on that a little bit.

Nishani Frazier: Thank you, actually for asking me that question because that was one of the things I also didn’t a chance to flush out in the article—and also one of the things that I thought was a successful idea. I don’t know why we are locked in this notion that trade has got to be within the United States just because you are a local group, right? One of the things that I thought was really fantastic was Cleveland was talking about creating the individual trade relationships from cities to whole countries and companies and things like that.

I think you have to break out of the box of assuming that you have to create an internal relationship when it comes to the question of trade. I think that any nation that would be open to economic development, you can have conversations about what that economic development will look like. That’s not to say that there are not nations who won’t engage in some process by where they try to take advantage. Certainly there’s be that attempt among some groups of people, but I think that’s the case for all and I think you can set the standards for how you expect a company to operate.

Whether you go to Scandinavia, whether you go to China or whether you go to some place in Latin America, the question is: are any the companies at any place in the world producing anything that would be of use to your own community, in which your community could participate as both laborers and partial owners in that production if it comes to your city? I do think we have to think outside the box and I think we also have to think the ways in which mayors assume that they have one relationship and that relationship is to the city in which they are working.

I think it would be really powerful to create a network of the radical Black mayors, but I want to be very specific. Those who are thinking about ways of broadening wealth access or economic access within in the community and perhaps trading between each other. For example, in Newark, they have the Vertical Garden. Who’s to say that the Vertical Garden can’t ship food to Jackson, Mississippi if Jackson, Mississippi is producing an item like hemp, for example? Hemp is beginning to emerge as a very popular item in a lot of Southern states because of its many industrial uses.

If I have hemp produced in Jackson, Mississippi, can I send that to manufacturing companies in Newark? We have to think about ways of creating relationships with each other based on our spaces and the ways in which we could serve each other, based on the nuances on what we can bring. I want to also be clear, populism is defined multiple ways and I do make it clear when I define populism, I talk about the history of populism from the 1890s. I’m very clear that there’s a distinction between populism as an economic way of being, of people being able to broad access to the economic system within the United States versus a populism that translates as simply wide appeal.

With Donald Trump, we’re simply talking about someone who is creating and generating a great deal of interest and has wide appeal; he certainly doesn’t have any kind of economic program to speak of, but even if that economic program existed, none of it entails this whole question of shared wealth or broad wealth ownership. This is about controlling the trade and these business relationships where there’s still an individual owner.

Adam Simpson: Right. That brings us my final question, which is about Trump. What lessons do you think community development practitioners in our current age under Trump can learn from predecessors experience under Nixon and Reagan?

Nishani Frazier: Well, I have to tell you, Nixon is different from Reagan. Reagan is different from Donald Trump. As much as I refer Richard Nixon as a trash can lid, there is no comparison between that trash can lid and Donald Trump, where you are in the dump itself. Within the Nixon Administration, I always refer to the Nixon Administration as a kind of a hydra. Multiple heads and the problem with the Nixon Administration is you had the conservative hydra. You had the liberal hydra. You had people like Len Garment, who used to work for the Kennedy Administration. You had James Farmer who’s a former director of CORE. He’s working in the Nixon Administration and they’re doing things separate from this other head, which is including people like Donald Rumsfeld, of course, extremely conservative. You have some folks like George Romney who was, not like his son, on the liberal end. There was actually a liberal side, people where you could have conversations about this idea of group wealth. In fact, although the Community Self Determination Act is not successful, it does lead to a huge conversation about what they call ‘expanded ownership’.

That expanded ownership conversation takes place only among the George Romneys, the Len Garments, the James Farmers—it’s not able to break in on the conservative side, because for those folks, that’s fundamentally communist and they can’t get past that. So at least within the Nixon Administration, there was a person or group of persons whom you could have a conversation with about this idea, even if the ideas effectively did not go anywhere or would be translated into something very different. With Ronald Reagan, by the time he comes in, he has twisted the idea of expanded ownership into something that is not reflective at all of this whole idea of community-based broad wealth ownership.

His version of expanded ownership is expanded capitalism. By the time we get now to the Trump Administration, we’re looking at a person who has no liberal wing, if you will, within the administration. You have only the right and the far right and those persons are heavily engaged in socially regressive policies with regard to African-Americans, Latinos, gay people, that kind of thing. Political policies that are designed to undermine the political power of those groups. The economic components of this administration, unfortunately are not very far ranging or visionary at all.

They have a promise for poor White Appalachians in the coal mining areas to bring back coal, for instance. In fact, that has led to the opening of a number of coal mines. What the left hand giveth, the right hand taketh away. They did that by dumping all the environmental regulations. Yeah, you have a job, but don’t drink the water because they have fundamentally given up on what it means to have a citizen company be responsible for what it does within the community. These folks have policies that are geared toward the fastest outcome possible without the vision of what it could mean broadly for the community in the long-term because ultimately, coal is gone.

And it was already on the decline, even without the regulations. Instead of thinking about transitioning to hemp or some other product that might grow well in a mountainous areas or finding some kind of alternative economic engine, they simply turned back the clock. I think that is fundamentally problematic. They don’t articulate a vision for any kind of economic development, or of capitalism, for that matter. They don’t even have a vision for capitalism, straight out. I think that for an organization that’s operating in this period, the focus has got to be: one, looking at foundations again if you’re getting started as an organization, and then two, finding ways to make that money work for you over the long-term.

You cannot go these foundations and say, “I want to do this program,” and then come back, “I want to do this program.” These programs in one way or the other have got to feed back into your economic stability as an organization. It’s got to do so on a long-term basis. There’s a bank called Self Help in Durham, North Carolina. It distinguishes itself partly through the communities that it chooses to loan to as a way of serving the community. (They’ve actually declined in terms of their Black loan services, so there’s some push back on that.) One of the elements that I thought was interesting about Self Help is that they have what they call a 10% path.

That means that are they are getting funding and doing the work that they do, there’s 10% that goes to a kind of an endowment, so that at any time that there was a problem with political pressures, with issues that they made around funding development projects and things like that, they could withstand those pressures and financially remain stable. I think at this point, it sounds very archaic, but we need to think about broaching this idea of tithing to oneself, paying oneself, institutionally, organizationally, as a city so that you can stabilize not just for today, but for the future.

Adam Simpson: The one bright spot today seems to be that there is a lot of energy in particular around local organizing at the city and the state levels, given the absence of partners at the national level.

Nishani Frazier: Honestly, I think that was similar to the 1970s and the Nixon Administration. Not as bad, certainly as currently, but the truth be told, for most of these cities then finding partners was quite a difficult feat. Even the federal government. When New York City has its problem in the 1970s, as it said in the newspaper headlines: ‘Ford to City: Drop Dead!’. New York City is under financial crisis and they’re not getting help from the federal government. It’s the state that eventually stepped in. So I think that where we are is actually not historically new, but it’s not ever been this extreme either. I think that absolutely feeds into the energy that we’re seeing now.

Adam Simpson: Right. Well Nishani, that’s all the time we have today. I just want to recommend to our listeners again, the book Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. Again, thanks for the conversation. I can’t wait to share it with our listeners.

Nishani Frazier: All right. Thank you so much. This was fun.