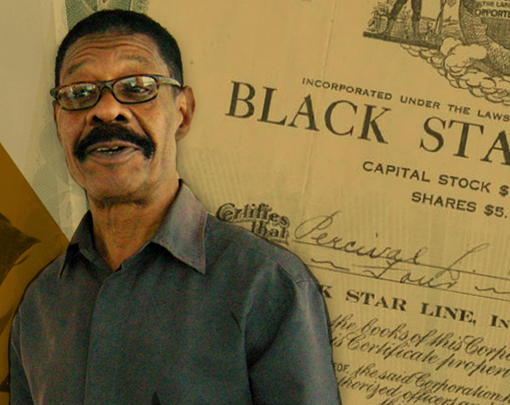

This week we’re looking at building worker ownership in the economy from a policy perspective. Given new policies proposed by a host of Democratic candidates, worker power and inequality are two topics very much on the policy agenda for the 2020 presidential race. Today we’re talking about why worker ownership is a particularly unique strategy for addressing both of those challenges and about the policies thus far that have entered the discourse. We’re joined by Next System Project Policy Associate Peter Gowan, as well as Mo Manklang, Communications Director for the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives.

The Next System Podcast is available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, Tune-In, and Spotify. You can also subscribe independently to our RSS feed here.

Adam Simpson: Welcome to the Next System Podcast. I’m your host, Adam Simpson. A quick reminder that you can get all transcripts of our conversations online at thenextsystem.org/podcast.

Today, we’re talking about employee ownership and, more specifically, a range of policies that aim to increase the number of employee owners in the United States. Our guests today include my colleague, Peter Gowan, a policy associate with the Next System Project. Peter, thank you for joining us.

Peter Gowan: Thank you for having me, Adam.

Adam Simpson: And joining us as well is Mo Manklang, communications director for the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives. Mo, welcome to the Next System Podcast.

Mo Manklang: Thanks for having me. I’m glad to be here.

Adam Simpson: One prominent issue in the public discourse is the widening gap between the rich and the poor, and the intensification of economic inequality. With the United States gearing up for election season, numerous presidential candidates are discussing how to address inequality. Many propose progressive taxation. Businessman Andrew Yang is focusing his campaign around the idea of a universal basic income. Senator Cory Booker has proposed baby bonds, a program that would essentially guarantee a small trust fund for every American. Most recently, though, Sen. Bernie Sanders has emerged by coming out in support of worker ownership in a few different ways that we’ll dig into in a little bit. But I’d like to hear from both of you. No matter what you might think of the other policies, when it comes to addressing economic inequality, is there something in your mind that uniquely sets employee ownership apart from other proposals that candidates might have otherwise suggested?

Mo Manklang: Yeah, absolutely. I think that in this particular political moment, it’s kind of hard to find opportunities where people can come together, no matter what their backgrounds are and what their party affiliations are. Employee ownership lands in this really great spot of being something that’s attractive on both the left and the right because it’s about empowerment; it’s about workers being able to take control of their business, their workplace. In this respect, in the ownership piece of it, I think it’s something that is easy because we’re not regulating anything, we’re not taxing anything. It’s all about creating really strong businesses that can thrive in the economy as it exists right now.

I think that while the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives covers not just worker ownership or employee ownership but also democratic governance, this is, I think, something that’s going to go a long way in helping to raise the public consciousness about what it means to have a voice in your workplace. And I think that it’s something that people are starting to understand, but it’s something that, by and large, people widely agree is good for everyone.

Adam Simpson: Absolutely. And Peter, what effect can worker ownership have on inequality more broadly?

Peter Gowan: I think that one of the really important things is that when you’re trying to address economic wealth and equality, there’s a hell of a lot of things you can do within the framework of boosting people’s rights at work—promoting labor unions, increasing the minimum wage, stuff like that. But ultimately, within the framework of the economy that we have at the moment, firms are primarily managed and owned and run on behalf of a pretty small class of people, people who own shares in companies, who get all of the surplus that comes out of them, and who through shareholder meetings and other things pick the directors who hire the executives. It’s a very, very sort-of top-down system.

I think that one of the exciting things you can do with worker ownership is that you can start to transfer both income rights to workers, like getting a share out of the profits, which the business that you work in produces, and also some of that control so that workers would have a bigger voice in how their work is structured, what the company does, what wages and hours are like, what the working conditions are, the company’s practices in terms of sustainability and diversity. So there are a huge amount of things that more democracy in the workplace would be able to impact on. I think that broadening the number and scope of employee-owned companies can have a really, really transformative impact on the economy for those reasons.

Adam Simpson: I want to dig into the specific policies that Sen. Bernie Sanders has that reemerged in recent weeks. But before I do that, I want to go back to Mo and I want to ask can you describe a little bit about what the current policy landscape in the United States looks like vis-a-vis worker ownership?

Mo Manklang: Sure. It’s actually a really exciting time. For a sector that is relatively small, right now there’s about 450 worker cooperatives and democratic workplaces across the country that we know of. Those are the ones that we’re able to track and understand how they’re functioning. That represents, I think, close to 8,000 workers across the country. It’s a relatively small piece of the pie, but I think when you look at it in tandem with the employee stock ownership plans, then it has a really broad impact.

I think these two different models are able to feed off of each other in terms of number one, the hard numbers that are there in terms of economic dollars that are flowing, and also the idea of a little bit of what Peter was talking about, voice and helping to train people into the idea that they are able to have some sort of say in the work that they’re doing every day.

That was brought really to light, I think, last year in August of 2018. We passed the first-ever legislation that really focused on worker ownership. It’s the first one in 25 years, I think, that’s meaningful around employee ownership, worker ownership, what have you. This was the first one to actually name worker coops in a meaningful way. So that one is specifically around directing the Small Business Administration and its activities to understand why is it hard for people to access loans through the SBA and also to promote the idea of worker ownership writ large across the country throughout their programming so the people understand that it’s an option—particularly in the area of converting their business.

We’re looking, right now, at this really big issue—some people refer to it as the silver tsunami—where you’re looking at huge portions of our workforce owned by people who are approaching retirement age. So they’re not going to be around their businesses forever. We’re starting to look at succession planning. First of all, most people don’t have that. A lot of people are starting to assess, what are they going to do? Are they going to sell it to a bigger business? Are they going to close the doors completely? We’re encouraging people to look at the idea of selling to their workers. That’s what the Main Street Employee Ownership Act is all about. It’s about figuring out ways to fund worker ownership and ways to help raise the public consciousness around that.

That was a really big impetus. That’s not to say that there haven’t been a lot of really strong opportunities for people and initiatives have been going on across the country. There are cooperative allies, like the city council in Boston. The city of Philadelphia just in 2018 added a budget line item around worker ownership in doing development work. That was feeding off of the successes in New York, where there’s I think more than $3 million right now being spent towards, basically towards worker cooperative development. That’s following long-standing successes in Madison, Wisconsin and the Bay area of California.

We’re seeing pockets of initiatives that have been popping off for a little while, and I think the Main Street Employee Ownership Act really was a pivotal moment that helped to just raise people’s awareness. We went from people not necessarily understanding worker cooperatives as a structure to it being featured in the presidential campaign announcement video of Kirsten Gillibrand. That does a lot for helping people to just know what that is and start to grab hold of that as something that is both bipartisan. It’s something that people can talk about when they’re formulating their stump speeches and things like that. We’re getting a lot of inquiries about that and we’re seeing, both at the state level and at local levels, people feeding off of that energy to take worker ownership and formulate legislation that’s applicable at the local levels.

Adam Simpson: As I mentioned, Peter, last week Sen. Bernie Sanders made headlines by advocating for yet more proposals to help expand employee ownership in the United States. Can you tell us a little bit about the content of those proposals?

Peter Gowan: Yeah. The first thing was that Senator Sanders reintroduced a couple of I think very important pieces of legislation. One of them is the WORK Act, the Worker Ownership, Readiness, and Knowledge Act, which would create a new body within the Department of Labor that would provide outreach, technical assistance, to sort of help employees who want to become owners, or business owners who are considering selling to their employees, help them learn about what’s involved in a transaction like that, help the workers understand what they would be taking on in taking over a company. It would make a number of annual grants to workers or companies and generally help provide some assistance for those technical assistance aspects of it.

The other piece of legislation which he introduced is the Employee Ownership Bank Act, which would create an institution similar to the Export-Import Bank in structure. It would provide loan guarantees, subordinated loans, and some more technical assistance to employees who want to buy out up to a majority worker ownership within their firms. So it would have to go up to at least 51% in order to receive funding under the Employee Ownership Bank Act. That would be either through ESOPs (employee stock ownership plans) or worker-owned cooperatives. Those are two pieces of concrete legislation and we have all of the full details on that stuff.

What also came out last week in The Washington Post, who did an interview with Senator Sanders, and asked him about some other ideas that he was considering. One of them was that he is working on a plan for co-determination, which we’ve seen other senators talk about before. Senator [Tammy] Baldwin introduced a bill that would give a third of board seats to workers at publicly traded firms. Senator [Elizabeth] Warren introduced one that would give 40% of board seats at publicly traded companies and a range of privately held companies over a particular size. And Senator Sanders seems to be working on his own proposal on that. That’s not a worker ownership policy, but it is in a sense a worker control policy as broadly within this family of economic democracy.

But the one that really stood out, at least for me because this is something that I’ve been writing about for a very long time, was that he’s considering creating a policy that within large firms, they would be required, over a period of time, to transfer shares of ownership on an annual basis into a worker fund. In the United Kingdom, these are called inclusive ownership funds. They’ve been adopted as Labour Party policy. There’s a bit more detail on that there. The Sanders plan, he’s said that there’s no full details on this stuff yet. I’m very, very excited to see what it actually comes out as in the end.

:In the UK, the proposal is that every single year, firms with over 250 workers would have to put 1% of their shares into a worker fund every year for 10 years, up until they have 10% of their equity within a worker-controlled fund that workers would elect… a board that would vote those shares. Workers would receive an individual dividend. The shares would be asset-locked within that fund so that workers couldn’t sell out of them at any point. They would just receive an ongoing annual dividend. They don’t take on any substantial risk if there’s a share price drop, but they do benefit when the firm is going on at a reasonable level of profitability. I don’t know if the Sanders plan looks exactly like that, but it looks like he’s looking at proposals that are very, very similar.

Adam Simpson: So, Mo. Coming from the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, I’m curious what the reaction was over there. What was your view when you first heard about these proposals? And as Peter said, I think the Employee Ownership Bank and the WORK Act are somewhat preexisting. But what do these policies mean from your perspective?

Mo Manklang: Yeah, the WORK Act and the Bank Act were really exciting and those were a few years ago. I want to say maybe 2017 is when those were introduced, or maybe early 2018. I think this is just building upon that. Bernie comes from obviously Vermont, and they have a really long history of employee ownership. So he has experience in this; it’s not coming out of nowhere. And I think that’s really important. I know that while not everyone agrees with Bernie, you can’t disagree with fact—well, I guess you can—but you can’t disagree with the long history of almost 20 years. There’s been an employee ownership center in Vermont that we’ve worked closely with that has proven that employee ownership is a really strong model for really solid, stable businesses.

We were really excited to hear about these new proposals that are being formulated right now. I think the jury’s still out on the specifics of those. But I think the most important piece of that is really just the idea of talking about this on a national scale. We don’t see that all the time. Right now is the time when we’re formulating the platforms on which people are going to build their presidential campaign. We’re seeing people from all different sides putting out bills around employee ownership in one way or another. And I think that’s really exciting to center workers in the debate who are going to decide our next president. I think that it’s a really exciting time, if only because we get to actually take this moment and craft what the next year and a half of listening to presidential stump speeches, debates, and all of that.

It’s really important to look at this as a moment where we can change the narrative, because people don’t think about business in this way in this country. Right? There’s long histories in Europe that we can point to and say, “This is the base of really strong economies.” But if you’re looking at America, we’re not thinking necessarily about workers within this way, right? We’re not thinking about collective ownership or collective governance. And I think this is an opportunity to change that narrative, and that’s really, really exciting.

Peter Gowan: I totally agree with you on that, Mo. I think that one of the most exciting things about that is that we’re now having multiple presidential candidates talking about worker ownership as an important part of their policy agenda. As you said, we saw Kirsten Gillibrand talking about her achievements with the Main Street Employee Ownership Act. And I think that what Sanders is doing on this is he’s sort of staking out his take on how we get to the next step on this. I’d be really, really excited if we were seeing people standing on a debate stage, talking about how do we make more workers into owners? How do we take this model that we know works for people, that improves people’s wages and conditions, that gives them more autonomy and voice in their daily lives? How do we make that not just something that’s for a few people, but how do we expand that so it is available to most people in the economy, that this becomes a sort of foundational building block of a new democratic economy?

Mo Manklang: It’s a win for everybody, right? How often do you get to see Kirsten Gillibrand cosponsor a bill with Susan Collins and Ben Cardin from Maryland and Todd Young from Indiana and Cory Booker? You’re seeing a lot of different kinds of perspectives that are all bought into this one idea of worker ownership. I think that that’s really, really important. That makes it something that is both a new topic to talk about, and one that people can come out with their different strategies to support. I think that it’s a really transformational moment.

Adam Simpson: It’s also, in terms of a transformational moment, worth noting the ramifications in terms of an Overton window. This is going to be a normal part of the conversation, talking about worker ownership. It reminds me of in the 2016 campaign, Sanders was talking about Medicare for all, and, not that everyone is accepting it, but it seems to be much more acceptable in the discourse now. To suggest that, actually, people should have healthcare—not access to healthcare, but people should have healthcare.

Peter Gowan: Yeah, I think that when you have people staking out very, very clear principles, forthright positions on things, it creates space for people to talk about all of the things, whether up to that, or actually doing these very, very ambitious policies. Up until recently, as Mo said, there hadn’t been that much discussion about employee ownership. And now we’re starting to see that there’s a real debate happening.

We’ve seen similar things happen on the codetermination side, where we had one bill introduced by Senator Baldwin, now we have one by Senator Warren, and now Bernie Sanders is considering something quite similar himself. As these ideas get introduced, and they get put out there and people start talking about them, you actually start seeing that things that people thought— “Oh, there’s never going to be a huge amount of public support for really expanding worker ownership”—well, if people start talking about it, then that support can really come into existence, and people will start caring about it, not just on the federal level, but when people get turned onto this by Bernie Sanders, and then they call up their state legislators or their city councilors and be like, “I want you to make a fund to support coops in my city.” Maybe this doesn’t happen at the federal level immediately, but in a lot of cities, there’s probably a lot of scope for this to happen right now if we start a real national debate about it.

Adam Simpson: Peter, I want to follow up here because, in terms of starting a national debate, the Democracy Collaborative actually did some polling recently testing out the public’s view of worker ownership in different ways. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Peter Gowan: We had some really, really exciting results on this. We tested a few different policies that would radically expand the scope of worker ownership and really put it at the center of what we want the next economy to look like. One of them was the policy that is quite similar to what Bernie Sanders is talking about: this inclusive ownership fund idea, where companies would have to put a percentage of their shares every year into a worker-owned and controlled trust. We tested that both with that trust going up to a size of 10% of the company and up to a size of 50% of the company. So the Labour proposal in the UK is 10%, and then we also wanted to test something a lot more radical than that, so, over the course of a generation, all large companies in America would be at least half-owned by their workers.

In both cases, over a majority of the population supported it, including half of Republicans—a vast majority of Democrats, and more Republicans supported than opposed it. Which I think really speaks to the fact that, while a lot of Americans are a bit skeptical of government owning things, they’re not wedded to the idea that only a tiny percentage of wealthy, extractive, one-percent business owners should own everything. They’re very, very favorable to the idea that workers should own and control the places where they spend the majority of their waking hours, that they actually have some knowledge which could help them to run effective businesses and that they should get a share of the profits. That’s one of the policies.

The other one that we poll tested, which did even better in the polling, was a policy that, again, the Labour Party in the UK has adopted, and they have some really great policies on worker ownership. Which is that when a company is being sold or closed, that the workers would get a right-of-first-refusal period, where they would get some period of time in which they would have the right to match any offer that a third-party buyer has made to purchase out the assets of this company, and that they would get financial and technical assistance in order to do that. Now, that policy polled at 69% of Americans in favor. Majorities in all parties, across all racial and gender and spatial categories, urban, rural and suburban. There’s huge support for this. Now, this is, in a lot less expansive form, in the Employee Ownership Bank Act. That’s one of the provisions that I didn’t mention earlier, where, if a work site is being offshored, the workers would be given the chance to buy that out. That’s one of the components of the Employee Ownership Bank Act. If a company wants to ship jobs to China, the workers in America would get the opportunity to take over their plant.

You see that would have an impact on some of the places in Lordstown, Ohio, where you’re seeing some of the General Motors plants that are closing down. The workers there would have the opportunity to take it over themselves. They could come up with their own business plan, like transform that capital into something that would provide a viable product for themselves, if that business works—which it won’t always. But there is a huge support for giving people the opportunity to decide for themselves whether they want to take over their company and to buy it out at the price that they would otherwise sell to another person.

Our polling has shown that there’s a huge appetite among Americans for employee ownership to be, not just something that happens in exceptional cases, but that we can build into the core of how businesses are owned, run, and sold in this country. I think there’s a huge space for political leaders and candidates to move into the space.

Adam Simpson: Mo, when I hear stuff like this, it actually reminds me—and forgive me because I’m going off script again—of this broader debate going on right now about the future of work, and where people are talking about what the workplace is going to look like in 10 or 20 years or maybe even longer, and people talk about artificial intelligence and automation. There are much more real, tangible things going on right now, like what people refer to as the fissuring of work, more part-time and contract types of labor. But I want to hear from the worker ownership space: In your mind, what should we be talking about? When we think about the future of work, given where the energy is right now, what the public is thinking about worker ownership, can you tell me, what’s your take on the future of work, this debate? And how can we bring employee ownership into that conversation, when people are talking about the future?

Mo Manklang: This has never been a more important moment to talk about these issues. Like you were saying, the future of work looks really different than what it traditionally has looked like. You’re seeing so many people taking advantage of the progress in technology to experiment with all these different services like Lyft, Uber, Fancy Hands, TaskRabbit. Those kinds of things that are farming out work, but they’re not actually giving back the value that people are creating through the work that they’re doing, right? It makes it very easy for people to buy in, which is great for people to be able to go from no job to driving in the space of a day or two. But, it also means we’re not helping people to think about the long term, right? We’re not helping people to think about the longevity of their car, their health insurance, all the overhead that comes along with those things; it’s all being slowly pulled out of the workforce. Whereas, if you looked at your traditional 9-5 job that anyone from my parent’s generation was looking at, they’re providing a lot. They’re the reason that my mom always wanted me to get a government job, because they take care of you. But we’re looking down the barrel of this future where nobody’s taking care of the workers at all.

So we have to start organizing to figure out what that looks like, and how we’re putting into place safeguards to make sure that people aren’t able to just extract all this value out of people who are driving, who are cleaning houses, who are taking care of the infirm. That we’re making sure that these people are being taken care of. There’s a reason why the Game Developers Conference that just happened a few months ago, that a huge push of that conference was just talking about unionization and formulating worker cooperatives: because it’s a flash point. People are worked to the bone and they’re not getting any benefits out of it.

We’re seeing people start to realize, “Oh, wait. We should be fighting for ourselves.” You’re seeing this renewal of the energy that came with the labor movement and seeing people get really angry at what’s being done to them, but they maybe got down in the past where they’ve been working so long in this way, that they kind of forgot that that was even a thing that they used to have access to, like healthcare, and a living wage, and reasonable hours. That’s the kind of thing that we’re going to see more and more. I think it is going to be a centerpiece of the presidential debates. And it should be, because you’re looking at a workforce that’s really increasingly moving towards the gig economy. People want flexibility, right? People, like the millennial generation and younger, are really wanting to have flexibility, but they’re also not able to save for retirement and they’re not able to really take care of their families. I think that it’s a really important discussion to be having right now.

Peter Gowan: I think that it’s really important to distinguish between people saying in surveys that they want flexibility, which is often true for a good number of people, and the sort of things that get sold as flexibility by a lot of these big businesses, which often aren’t. The workers don’t feel like they have flexibility, they feel like they need to be on call all the time. They feel like they need to be driving cars at all hours of the day in order to squeeze out a tiny bit of money because they realize that actually now they’re driving an Uber all day, their car has to go through a lot more repairs, and Uber doesn’t pay for them because they’re supposedly independent contractors.

I think the one really important thing that we need to do is to realize that we shouldn’t sleepwalk into a labor market where we let these companies effectively innovate their way out of labor laws and the basic protections that people have won over centuries. Those things exist for a reason and they’re not outdated, they’re just awkward for business owners. I think that we, especially as we move towards having a more democratic economy, one of the really important things we need to do at the same time is take a long, hard look at overhauling how we categorize workers, how we structure labor rights to ensure that everyone who might want more flexible hours, but also want protections in doing that, that we look at models, like platforming cooperatives for things like ride sharing, where people are able to share in what comes out of it, have similar things to how a lot of individual farmers use cooperatives to market their goods. There are ways that you can use these democratic methods as part of a broader overhaul of how we ensure rights for workers, how we ensure that unions are able to organize in these industries.

I think one other important thing is as we’re designing these broad-based employee ownership policies, things like the right-to-own policy, things like inclusive ownership funds, is that we don’t let workers be excluded from these things because of having a precarious employment status, that we try to make sure to include people who are doing the same jobs that a full-time employee or a contracted part-time employee could do, that they actually get to share in the profits as well and that they also get a say in how the business is run.

There’s a whole lot of work being done by some really great labor economists on how we restructure our labor market so we can take account of the needs of the present, but that we also do it in a way that increases rather than decreases rights. I think that that’s really important for how we design worker ownership policy. But it’s important for how we design economic policy across the board. This touches on almost everything.

Mo Manklang: Absolutely. I was looking at this business journal report and it was a prediction of what small businesses are going to look like in the U.S. over the next several years going into 2021. Their numbers were that there were 3.19 million people in 2016 that were working in the gig economy. But that looks like it’s going to almost triple by 2021. They’re expecting that it’s going to be 9.2 million people working in the gig economy. This is the work that needs to happen yesterday because this is increasingly important. People are just trying to figure out a way to live, right? And that’s really the backbone of a lot of worker cooperatives across the country. There’s not any options, and that’s why you’re seeing the demographics of worker cooperatives moving towards communities of color, women, particularly Latina women, who are routinely worked into jobs I’m sure a lot of them really love—and we all value the work of childcare providers, home care providers—but they’re also very insecure industries. These are the industries that have the biggest turnover, the biggest rate of workers being taken advantage of, of not being able to voice their opinions or needs or having their schedules accommodate the needs of their family. I think that a lot of the workers that are turning towards worker ownership are doing it because they don’t have any other options, right? And that’s why people, it’s a lot of the reason why people find themselves within the gig economy. It’s because they don’t have an option.

If we’re finding ourselves in a place where the solution to unemployment is gig work, then we really need to take care of these people and have the foresight collectively to look at that and iterate just the same ways that the technology industry iterates experiments really quickly. There are some really exciting things that are happening. Up & Go in New York is a network of home cleaning cooperatives, and it’s a cooperative itself. They ensure that the people who are working in cleaning those homes are able to have a say in the platform itself, and get a share of that value that they’re creating. Or Alia, that’s a project of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, that is focusing on portable benefits so that the benefits are actually tied to the person, rather than the job. Because you lose your job, you lose all your benefits. What are you going to do?

So I think that it’s a moment of, yes, we have to raise awareness. Yes, we have to be really thoughtful and smart about the policies that we’re creating. And we have to make a lot of technological leaps and iterate on this work really quickly.

Adam Simpson: We’ve only got a few minutes left, so I do want to bring us back to the policy question. We’ve been all over the map today, really, about the Employee Ownership Bank, the WORK Act. We’ve talked about inclusive ownership funds, an exciting thing going on in the UK. We’ve talked about co-determination. We’ve talked about ESOPs and local energy around organizing worker cooperatives. But I wanted to ask all of you, are there policies that you would want to see policymakers looking at, whether at the municipal level, or at the state level or federal level? Are there policies you would want policymakers looking at, offering for public debate, that would further help give worker ownership a boost? Mo, could I start with you here?

Mo Manklang: There’s a ton of ideas. A lot of the work that we do at the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives is to understand what are the challenges that people are running into and how do we address them, at the federal level and at the state level and at the local level. Some of the things that I think we’re seeing is a focus on conversion. So education is a lot of what the Main Street Employee Ownership Act does, but actually attaching dollars to that because that acts as primarily a directive. We actually need dollars to do the kind of education and workforce training that’s necessary in order to educate people about what it takes to convert your business to worker ownership, because in a worker cooperative, it’s not just the ownership part, it’s the governance part and helping people to understand, what does that mean? How do you understand your books? How do you understand the management structure of your organization? We’re not trained to think that way.

It is an opportunity for people to build skills. That’s why it’s so attractive across the board, because it’s not just about a person going to work and doing their job and clocking out and going home. A lot of it is actually about providing leadership opportunities and skill building, and allowing people to be real entrepreneurs.

I also look to examples from all around the world that have been proven to work really well. In Italy, they have one where they actually take a portion of the taxes from cooperatives and put them back into workforce development. So, we’re looking at opportunities for us to pull out of the taxes that are already happening—not adding taxes or adding some other money that we don’t know where it’s coming from—but actually pulling from taxes that are already being collected and putting that into this education, technical assistance, and the infrastructure that’s needed to promote worker cooperatives and worker ownership as a whole. I think those are two really important things.

Peter mentioned right of first refusal, making sure that people even know that that’s an option. One thing that we don’t talk about enough is data. That’s why I was really excited to see that as part of the Main Street Employee Ownership Act, we’re looking at the data that’s needed to even understand what the issues are. We need to know how much money actually goes into cooperatives and know how many jobs are being stabilized and saved. In Italy, they passed the Macora law that was specifically aimed at supporting worker buyouts, and that created in a very short period of time more than 250 new employee-owned firms and it either saved or created 9,300 jobs. It’s not rocket science. And it’s obviously something that’s resonating with a lot of people. I think, it’s a matter of people understanding what even it is and being exposed to it in a larger sense.

The last piece that I think is really important is creating the tax incentives to actually convert businesses, because there’s no problem and no lack of people looking to start worker cooperatives, and they’re starting to think this way, about collectively creating business together. But the idea of bigger-scale businesses converting to worker ownership, there needs to be an incentive, right? That’s why we see a plethora of ESOPs, because there were incentives in place to make it happen. Helping eliminate or reduce the capital gains taxes for owners that are willing to sell their business to their workers, and thinking about sale incentives, certain kinds of tax incentives, and procurement incentives, I think are really important to the future building out of this infrastructure in addition to the education that needs to happen.

Adam Simpson: Peter, anything you’d like to add in terms of the policy specs on worker ownership?

Peter Gowan: I think that I’d agree with a lot of what Mo said there. The right-to-own idea we’ve been discussing earlier that 69% of Americans support is quite similar in some ways to the worker buyout legislation in Italy in that it would provide a broad range of technical, financial and legal assistance to worker buyouts and would also give workers a right at the point a company is being closed to buy it out.

We go a little bit further and say that also, in the case of a privately held company being sold to a third-party buyer, that they would also get that right of first refusal in that situation as well. I think that a really, really attractive thing there is that the government and the bodies providing financial assistance would be able to focus attention on major buyouts that have a really, really strong chance of success rather than, as is seen in some cases, really only focusing worker ownership policies in troubled firms that are at risk of closure. Instead, you can get healthy companies into worker ownership that might otherwise be bought out by a competitor or a private equity firm that really has no interest in their success, that might be trying to capture the market for a company stocked by workers that are already there.

I think that that’s a good idea. It would make worker buyouts the preferred option in a lot of business transitions and could have a really positive impact on this silver tsunami effect that we were talking about. With the huge number of retiring baby boomers who often have no succession plan, now we give them a default one. There’s financial and technical assistance available for them to sell to their workers. There’s a default buyer there for them. Instead of deciding this at the last minute, like “I’m going to sell to whoever, Bain Capital, who’s the only person who’s offering to buy this from me,” there’s actually a worker buyout that will preserve jobs and build a new democratic workplace, and maintain the thing that the retiring owner actually built, which I think a lot of them will like.

The other one would be this inclusive ownership funds idea, which I think would be really important in generalizing knowledge about employee ownership and participation in governance by creating these worker-elected funds within all large companies. As we’ve talked about, there’s a deficit of knowledge about this in a lot of workers and when they hear about a proposal for worker ownership, they might not even really know what it is or they might only have the vaguest idea. “Oh, I own my company. What does that really mean?” By really spreading it out, so that everyone would at the very least know a lot of worker-owners, if not actually be one themselves who would have some minority stake in their business, then at the point where there’s a possibility for a company becoming a majority employee-owned, there’s already some knowledge there. People already understand the benefits of profit sharing because they get a dividend from the profits in their company every single year, and they already elect people to perform the functions of the minority shareholder, which they would get through inclusive ownership funds. I think that really would massively deepen the level of knowledge across society about employee ownership and help us to move towards an economy where, as I say, the participation of workers in the governance and profits of their company is not something that’s exceptional. It’s not something that’s weird, like, “Oh, he’s a worker-owner in a coop. I’ve never known anyone like that before.” But it’s actually something that you kind of expect. It’s really there across society. Half your friends would be worker-owners. I think that’d be really great to see in a decade or two. We can all dream.

Adam Simpson: Or in a year or two.

Peter Gowan: Yeah, let’s say a year or two. Let’s go.

Adam Simpson: That brings us to about time, but I want to thank the guests today on the Next System Podcast. Mo Manklang of the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, and Peter Gowan of the Next System Project of the Democracy Collaborative. Thank you both for talking to me today about employee ownership.