The special two-part edition of The Next System Podcast features Clark Arrington, a pioneer in the cooperative movement, an innovative legal practitioner, and a leader in the movement for Black economic empowerment. Listen to Part 2 of the podcast here.) He now works as general counsel for The Working World, which provides creative, nonextractive financing and support for cooperatives. He is also well known in cooperative circles as the person who was instrumental in helping Equal Exchange grow from a small niche coffee roaster to a $70 million business. Arrington has an important and fascinating story to tell about his role in the struggle to build an economic infrastructure that not only empowers workers generally but confronts this country’s history of racism and its economic impact.

The Next System Podcast is available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, Tune-In, and Spotify. You can also subscribe independently to our RSS feed here.

John Duda: I think one of the things that I am really excited to get into is just the way that you have found your way into the cooperative movement, where you came from, how that’s all worked. You were born in Philadelphia. Tell me a little bit about growing up in Philly; what happened?

Clark Arrington: Well, I grew up mostly a single parent, my mother, who, God bless her, very competent responsible mother, woman. I had a great little childhood. My mother went to Talladega College, and I really should start there with my inception. That is because Talladega College would not have been there had there not been the revolt of the Amistad, which they turned it into a movie. They raised money to repatriate the Africans back to Africa, I think to Gambia. The surplus money was used to set up Talladega College. That’s where my mother and father met. I often speculate had there not been that uprising, had there not been that Amistad revolt, there would not have been a Talladega College, and in all likelihood, my mother and my father would not have met.

I was sent to a boarding school, a Black pre-college prep school, I guess you would call it. Palmer Memorial Institute, very prestigious school in its day. It was the school of preferred middle class, upper-class Black folk, diplomats, African diplomats, entertainers’ children. That’s where they went.

Long story short, I realized that going to a Black bourgie prep school also exposed me to certain things. We had an African Day every year. I was exposed to Africa at a very young age, at least while I was in high school. I started there in ninth grade. I also learned about Marcus Garvey in high school. It totally blew me away, but at that age, you’re learning about a lot of different things. You know nothing about anything. It doesn’t surprise you when you learn something. It wasn’t until later, I was at Penn State. From Palmer, I went to Penn State.

Through my undergraduate, didn’t hear anything about Marcus Garvey. This monumental Black guy. At that point, we were debating. This would have been early, late ’60s. I started in ‘65 and graduated in ‘69.

We were debating during that period. I was part of, I guess, the Black power, Black liberation movement, and part of that debate was whether or not you secured political power in order to get economic power or you secured economic power in order to get political power. I opted on the side, to me, it made more sense that you get economic power and then you had a choice as to whether or not to get political power. But when you began to analyze “Black capitalism”—and this is the Nixon era and there were all kinds of efforts to increase Black participation in the economy—you realize that this is the same system that evolved from slavery. It was like, no. I don’t want to emulate that system.

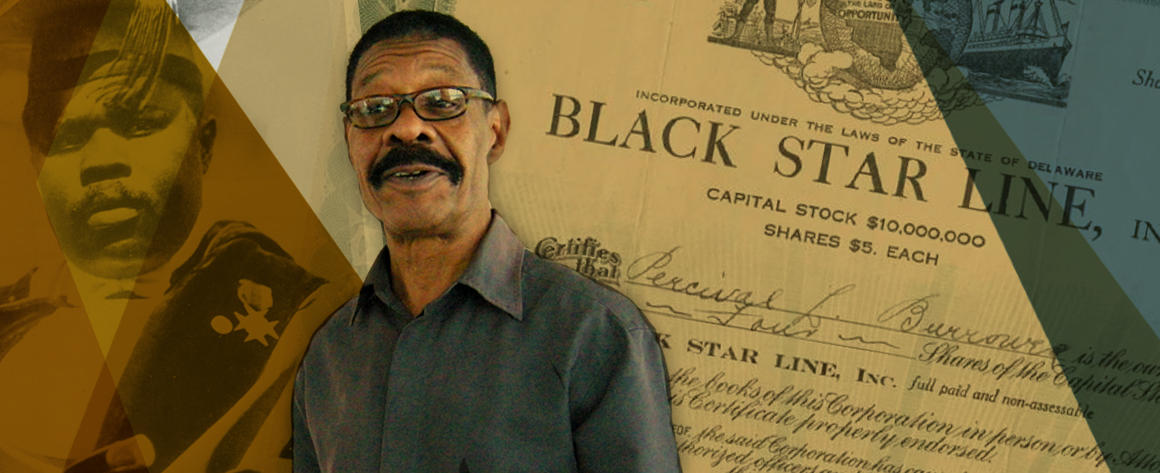

I looked at Garvey, and saw how he had accumulated a mass amount of capital from lots of people, small contributions, and created a serious enterprise, the Black Star Line, other businesses, and did it in somewhat of a cooperative manner. That impressed me. That led my thinking to, how a large number of people can pool small amounts of money to have large amounts of money in order to start businesses? From literally college on, that was always in the back of my mind while I partied and went to football games and chased and just had an outstanding social life, but I was always very concerned about capital accumulation and not replicating capitalism

John Duda: Penn State, what’s the climate there?

Clark Arrington: The climate was very interesting, because I’m coming from an all-Black, small institution to a big, White institution in the middle of nowhere.

I had a great time at Penn State. It was a big environment. I pledged a Black fraternity, but I also was very involved in all of the political activities at Penn State. I ended up heading this thing called the Jazz Club, which we would basically, we were the concert providers for State College, for Penn State. So we did concerts like, we did James Brown. We did Smokey and the Miracles. We did Duke Ellington. We would do big concerts in the beginning of the year, and then we’d do free concerts for jazz. The jazz concerts were actually free, because there was only a small number of people that really actually liked jazz.

I had access to a lot of money. I lent money to a group of political activists. I also funded the appearance of Dick Gregory. I guess it was during ‘68, one of the presidential elections, and Dick Gregory came. Again, Jazz Club sponsored it. Some of the more, I guess, conservative big-time fraternity boys were like, “Jazz Club, I’m a member of the Jazz Club and I don’t support these activities.” I had a good friend who was an editor at the school newspaper, Margie Cohen. She would write really nice articles and supportive editorials about what I was doing and why it was not an abuse of Jazz Club resources. While at Penn State, I helped start what was called the Frederick Douglass Association, which was the Black Student Association, which still exists today, and I got to have a relationship with the president of the University, Eric Walker. I’ll never forget that. At one point, I tore off the flag, lowered the flag in front of the administration building in honor of Malcolm X, I think it was an anniversary of his death or he may have actually been killed that day. There was a picture of me on the front page of all of the papers in Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Inquirer, Harrisburg. At that time, the president was before the legislature. It was a funding period, so he’s presenting his budget. Of course, there’s, “You’ve got to fire this kid, throw this kid out. Look what’s going on at this place!” He knew me. He was a good guy. He basically told them, “They didn’t destroy any property. All the property was replaced.”

Gosh, you can just imagine my parents and my relatives. They see my picture on the front page of newspapers. They hear about me wanting to be expelled from school. It was a dramatic period in my life, but the president of the University, Eric Walker, stood up and held. He had my back.

John Duda: All right. You’re at Penn State. You’re throwing great parties.

Clark Arrington: You wouldn’t believe.

John Duda: You’re bringing amazing concerts to the middle of nowhere.

Clark Arrington: Amazing concerts.

John Duda: In rural Pennsylvania, blowing people’s minds, making all sorts of trouble, winding up on the front page of the newspaper. What causes you to then go into law, go into cooperative development?

Clark Arrington: This is the Vietnam War era. Nobody wanted to go. The exemptions were changed. At one point, as long as you were in college, you were exempt. Then it was, you had to have a certain grade point average, and you were exempt. Then it was, when I graduated, there were certain professions that were exempt, one of which was teaching. I was accepted into grad school at UCLA for African Studies. I think it was African Studies. I don’t think it was African American studies. I was really on my way to UCLA, hoping I could figure out how to avoid the draft. I stopped by to meet some friends. They said, “You should teach.” Sure enough, that was what I ended up doing, teaching in Chicago, and I was exempt from the draft.

At that point, I was really interested in going to law. I realized I couldn’t sing. I couldn’t play basketball. I wanted social change. I wanted political change. I wanted economic change, and I felt having knowledge of the law was the best way to do that.

I wanted to go to law school for social change. I wanted to learn about how to accumulate capital from a large number of people with small numbers of contributions. I wanted to figure out, how could we do what Marcus Garvey did? Marcus Garvey was ultimately busted, jailed, excommunicated. I’m not sure the details of what the allegations were, but we know it was a Black man amassing a tremendous amount of power and amassing the wealth of the Black community.

I wonder to this day, particularly after reading Collective Courage by Jessica Gordon-Nembhard: What if Garvey had been successful? What model would that have created in terms of African Americans basically accumulating capital for profit enterprises and setting up enterprises?

Because of the failure, Jessica would argue that it was intentional. He was attacked. That thwarted, that had a real negative impact on African Americans accumulating capital collectively and going into business collectively. Had that been a success, God knows the direction we might have moved in.

When I graduated from law school, I was very active in law school. I also set up the Black Law Student Association at the University of Notre Dame.

Basically, I helped set up, when I was in law school, what was called a MESBIC, a minority enterprise small business investment company, which was this scheme that Nixon—people talk about Nixon, but Nixon, subtly, furthered Black capitalism, so to speak. Knowing that one of the real impediments to Black business development was a lack of equity—you could borrow money if you had assets, but the equity piece was missing—the MESBICs were designed to increase equity in Black businesses.

For the first year out of law school, I was helping finance Black small businesses in South Bend, Indiana, with this MESBIC. I had been accepted by employment by the SEC, and they agreed to defer me for a year to work on the MESBIC because they knew I was interested in capital formation, et cetera. I went to the Securities Exchange Commission in the division that regulated investment companies’ mutual funds. Basically, technically, it’s the ‘40 Act and the ‘41 Act. I learned a lot about capital accumulation, but at a level that was like, wow, we’re not going to set up these kinds of companies. I needed to know more about capital formation, not the actual what happens after you’ve accumulated. I learned, because I had friends who were in the other divisions, and it was a very productive period for me at the SEC.

Nevertheless, working for the government, working for the SEC, I’m right around the corner, right over there at Union Station, which is where we’re located. I was bored. Not bored, but I felt I’d learned all I wanted to learn, and I didn’t want to go to Wall Street. I wanted to get into the action. An opportunity arose from one of my mentors, Howard Glickstein. Howard connected me with a guy named Bill Taylor at Catholic University, who had a public interest law group, Center for National Policy Review, housed in the Catholic University Law School. Basically, what they did was they were the technical assistance arm of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. We also handled most of the appellate work. If the NAACP Legal Defense Fund had a case and it was going through the courts, we would write the briefs. We were the nerds behind the Civil Rights Movement. They hired me to open up the economic development arena. They had housing. They had education. They had public accommodations. Now, I was going to do economic development. I was the new kid on the block with a new arena. One of the projects was this Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway project that the Federation of Southern Cooperatives was involved in.

John Duda: For folks who don’t know about the Federation, can you spell out what the Federation of Southern Cooperatives is?

Clark Arrington: It’s a beautiful story. It’s a beautiful, untold story. Let me just say that the federation is a group of cooperatives based in the South. They have headquarters in Atlanta, but they have a rural training center in Epes, Alabama. Each state has a state association made up of cooperatives in that particular state. They’re mostly Black, but they’re also Hispanic or Latino cooperatives in Texas and in some parts of Arkansas, and there are also white farmers that are part of the Federation. But it’s predominantly Black.

The origins of the Federation go back. For anybody listening to this, you should just dig deep. After some success in the civil rights movement. the Voting Rights Acts were passed, and housing accommodation was passed. there were a lot of legislative achievements that occurred in the ’60s. As far as the civil rights movement was concerned, now it’s about enforcing civil rights. So you had the southern folk—this is Charles Prejean, McKnight from Louisiana, Sherrod out of Georgia—these guys are talking and they’re trying to figure out, what’s our next move? They were influenced by the nonviolent peace movement folk who were also part of the civil rights movement. They looked a lot more toward Gandhi, a lot more toward the East in terms of their inspirations. They were nonviolent. It was about nonviolence. India, the Gandhi people, they were into something called Constructive Movement after India became independent. One of their initiatives was basically, they called it the Free Land Movement. They convinced large landowners to contribute land to a trust in which they then redistributed that land to peasant farmers. They accumulated a million acres, if not more. I don’t want to overexaggerate, but they accumulated a ton of land. You really have the beginning of, really, the Community Land Trust movement.

Long story short, they toured. They looked at this. They came back and the Federation said, “We’re going to organize existing landowners into cooperatives and strengthen them as viable business opportunities and strengthen the food chain. That was the Federation. Their rural training center is in a town called Epes, Alabama, which is Sumter County, Alabama.

: This Tombigbee River borders their land. What the Corps of Engineers was planning was connecting the Tennessee River, which basically flows north, and the Tombigbee River, which flowed south. They were going to connect them. By connecting them, you would take literally about 500 miles off the Mississippi route going from north to south or going from west, deep west to south. They justified it by arguing that it would eliminate poverty in these areas in which it transversed. It went through the poorest sections of the United States, basically. Parts of Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama. I don’t think it touched Louisiana. Of course, the Federation was there saying, “Really? We’re on the river. We’re going to get all kinds of benefits here?”

At that time, if I’m not mistaken, Ray Marshall was secretary of labor. He has always been a friend of the Federation. He brought on folk who were affiliated with the Federation into the Department of Labor. At the University of Texas, where he resided before becoming secretary of labor, they did studies on the cost-benefits of these public works projects because, “Yeah, we’re going to eliminate. It’s going to be all kinds of economic development.” What they found was, yeah, in many of the cases, that’s what in fact happened, but it didn’t happen for the indigenous people. Indigenous people were left behind. They got totally screwed and exploited.

Armed with that information, the Federation was like, “Whoa. You guys need to do something special about this.” They formed what was called the Minority People’s Council on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. They had contracted with the Center for National Policy Review at Catholic University to help them with an affirmative action plan. We did administrative law. They needed an affirmative action plan that, for the first time, was going to be multistate. It was going to have to cover Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee. It was going to be multi-crafts, et cetera. It was going to be really a cutting-edge affirmative action plan. It’s like, “Okay, Clark. This is your job. This is your economic development project, et cetera.” That’s how I got introduced to the Federation.

On occasion, I had the opportunity to go there from DC. I was seeing the contrast between the urban DC thing and Alabama. The other aspects of it, a lot of my friends, a lot of the people I was working with in the Civil Rights Movement, they were enjoying their Mercedes-Benzes. They were enjoying their Coke. They were enjoying lots of good nights out on the town. When I’d go to Alabama, I’d meet these people who were part of the civil rights movement. They were just the salt of the earth, down-to-earth people. Just the contrast just really blew my mind.

As I became more involved and we got the affirmative action thing, I was like, “No, no. We need to be affirmative and be, if this is going to create all kinds of businesses, we need to be in a position to take advantage of this. I’m back to my Marcus Garvey thing. I know now about the ‘33 Act and Regulation D, because that was some of the other stuff I worked on at the Center, was how do you loosen up these security laws to allow for minorities or allow for Black people, allow for community groups to raise money without having to spend $200,000 for a public offering and hiring CPAs and attorneys, et cetera. You don’t need that.

We were able to develop a proposal that was funded by the Whitney Foundation that allowed for me to become a Whitney fellow assigned to the Federation and their Minority People’s on the Tombigbee Waterway Council. I moved from Washington, D.C.—Silver Spring, Maryland—to Epes, Alabama. I worked very closely with a couple, John Zippert and Carol Zippert and, of course, Charles Prejean and Wendy Parris and Alice Parris and George Parris and Ernest Johnson at the credit union. I just met these beautiful people. They turned me on to cooperatives. I was like, “What’s a cooperative? Cooperative principles? This is interesting. This is a little bit of an alternative to the Black capitalism model,” which I could see was not necessarily a model that I was enthusiastic about. I was enthusiastic about accumulating capital, but then turning it into something that was just going to produce wealth for an individual was not what I was interested in doing.

One of the things we did at the Federation, we need to raise money. Let’s raise some money. Let’s see if we can set up some enterprises. We set up. We’ve looked at the laws. I ended up, when I should have put together my proposal, the Whitney folk, as part of my fellowship, got pro bono assistance from Solomon Brothers and Cravath, Swain and Moore law firm. Can you imagine? I’m going to raise $1,000, but I’ve got Solomon Brothers and Cravath, Swain and Moore. No, we were a little more ambitious. We came up with a scheme where the funds would be contributed to a nonprofit corporation with the intention of ultimately being invested in a for-profit venture, but before the money would be invested in the for-profit venture, the members of the nonprofit corporation would get a disclosure statement, saying, “These are your options. You can leave your money in the fund, the nonprofit. You can have it returned, or you can allow it to become purchased shares in this for-profit venture we’re getting ready to set up.”

We raised, I may be exaggerating. My sense is we raised about $50,000. For the most part, it was like $100 here, $50 here. These were people, money under the mattress kind of stuff. They trusted us. They believed in us, and they clearly understood what we were attempting to do. I think some of them were certainly old enough that they probably had had some exposure to Garvey. They knew, or least their parents were shareholders in the Garvey ventures, but they knew this had happened before and we were revitalizing that. During the process, the Alabama folk came down on us, including Mr. Sessions, who at that time was, I don’t know, U.S. Attorney? Then there was another guy, Krebs.

John Duda: Sessions, Jeff Sessions [former attorney general and U.S. senator]?

Clark Arrington: Jeff Sessions, yeah. Another guy, Krebs. He ultimately became head of enforcement for SEC, but they came down on us. They served John and I with cease and desist orders. They threatened to put us in jail if we didn’t stop doing what we were doing, raising money. I will say John, he’s like, “Clark, is this?” “No, this is cool. We have not violated any laws. They’re not going to do to us what they did to Garvey.” Our Cravath, Swaine and Moore folk said, “Yeah, and we’ve got your back, also.” We had this brilliant, young lawyer named Rob Kindler. Rob, if you hear this, you know I love you and really appreciate all you did for us during that period.

We fought these guys, and we won. We beat them. We forced them to back down, because we hadn’t sold a security. We were soliciting membership interests in a nonprofit that you could get your money back. There was no risk, and here’s the accounts. We haven’t spent any of this money. This money hasn’t gone for anything. It doesn’t pay my salary. It doesn’t pay gas for me. All the money that we’ve collected, and the Federation is covering everything else. At this time, it wasn’t so much. Yeah, we were collecting money, but the Federation was under attack, period, by the FBI, the IRS. The Minority People’s Council was set up as a 501(c)(4), not a 501(c)(3). We were allowed to engage politically.

Of course, the white power structure said, “Them n****** using nonprofit money and church money, that’s illegal.” Go to the courthouse and see how it was. That then filtered, obviously, from the local areas to the Capitol to the United States government, to the federal level. That’s why the attack was just vicious, and the attack on us was just part of that. We defeated them. The Federation also. They couldn’t prove a damn thing. They couldn’t prove a nickel of 501(c)(3) money was used for any political activity. They subpoenaed records from Methuselah, go back to the beginning of, founding of the United States government. We ended up setting up a pallet manufacturing company as a worker-owned business. This was my first exposure to structuring a worker-owned company. I was like, “Wow.” It was very primitive, but it was cooperative principles. The Federation was used to setting up agriculture production cooperatives where you basically had different independent economic units pooling their resources to sell their products, to buy implements together as a cooperative, but they were individual, independent entities.

Now, we’re setting up an enterprise in which the workers in this nonprofit that now has shares in this entity are going to be joint owners. That part was a lot of fun. We knew how to, but running a pallet company? John and I didn’t have a clue. It didn’t. It wasn’t that successful. We learned a lot.

John Duda: There’s a history of worker co-ops that goes back through populist movement, Knights of Labor. There’s efforts to do worker cooperatives in the U.S. for a pretty long period of time, but as far as I understand, at this point in time, a lot of that history is lost. There’s no real, the technical knowledge, the legal knowledge. Are you all basically making this up as you go along?

Clark Arrington: We made it up as we went along. Of course, we had assistance from, some assistance from Kindler, from Cravath, Swaine and Moore, but they weren’t setting up worker-owned businesses to the extent they were. They were ESOPs and I’m not even sure ESOPs were viable at that particular time. You’re right. That knowledge, collective courage, there’s quite a bit of discussion of the history, but not of the details of how they were structured or the lawyers who helped structure them. Let’s find out, how were these deals structured? What were some of their options in terms of how ownership and how distribution of profits were to be structured? Right, No, we didn’t really have a clue.

I left the Federation, and I ended up going to Mississippi, practicing law with a guy named Wilbur Colon, who I had met, who was also a legal intern at the Federation. On the weekends, we’d fantasize about having our own law firm and he was much more of a traditional capitalistic lawyer. I was much more of an activist, but we both had a little overlap, so it made sense. We set up this firm in Columbus, Mississippi.

: Ultimately, Wilbur, who was a Black Republican, was part of the Mississippi Republican party. So when Reagan ran for president, when he announced his presidency or whatever, he did it in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Philadelphia, Mississippi was where these three civil rights workers [James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner] had been killed. It wasn’t until, at the time Reagan went there, nobody had been made accountable for those murders. They knew the bodies and then these people got murdered. It wasn’t a big, big, big deal, but people knew, particularly in the South, the symbolism and what that meant. Talk about a dog whistle. You’re announcing your run for presidency in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

On his way back, he stops in Columbus and they arrange for Wilbur to greet him at the airport. That was on a Saturday. I guess he makes the speech Saturday morning. Saturday afternoon, he comes to Columbus. He’s coming off the plane, and here’s this Black guy greeting him. That’s what made the newspapers the next day, the New York Times. Not the Philadelphia piece, but the Wilbur, my law partner.

Clark Arrington: We began to drift apart a little bit, but all due respect to my law partner, who’s also one of my very, very closest friends. He remains in my love circle and forever will be in my love circle. He’s a brilliant lawyer. Our law firm, we were kickass. We were the first integrated law firm, as in we had Black men. We had Black women. We had White women. We had White men. We were the first in Mississippi to be that integrated, that multicultural, multiracial. There’s a New York Times magazine article that was written about my law firm.

John Duda: All right. You’re at this incredibly innovative, dynamic, well-connected law firm. How do you wind up in New England doing co-op law?

Clark Arrington: Somehow, I learned about this group, the ICA—Industrial Cooperative Association in Boston that specialized in setting up worker-owned businesses. They were looking for an attorney. The other issue: Moving to Boston allowed me to be closer to my daughter, who was in D.C., Silver Spring. I went to work with this very interesting organization. Wow, Mondragon, worker cooperatives, industrial cooperation. There was an attorney there, Peter Pitegoff. Peter, I guess, was planning on transitioning. There was enough work for, obviously, the both of us. It was just a very exciting period of time. Steve Dawson, I don’t know if you know Steve?

John Duda: Uh-huh.

Clark Arrington: He was the executive director. David Ellerman, he’s my god or guru in terms of conceptualizing what a worker firm looks like, should be like, what it should be, how it should be organized. Chris Mackin, who is one of my very, very close friends to this day. Chris and I just, Janet Saglio. This was just an interesting group of people. We all converged on this thing called the ICA Group. We were infatuated with Mondragon. This is late ’80s,

We were the worker ownership people. We were the cooperative people. We distinguished ourselves from cooperatives, because we were looking at the worker-owned firm in a cooperative context, whereas the cooperative world tended to be consumer co-ops and, for that matter, The consumer co-ops never really turned us on, because it was really the old, capitalistic model, especially in relationship to labor. You consumers own this place, and it’s in your best interest and your self-interest to pay these people as little money as you possibly can, because that increases the value of your shares and increases the amount of your distribution at the end of the year. That’s the old model. That’s the slavery model.

That wasn’t our thing. Our thing was, we wanted radical democratic change within the enterprise, not on the side, which was, you had that in Mondragon. You had these secondary co-ops, the hospitals, the schools, but the industrial co-ops, the manufacturing and the production co-ops were owned by the workers, so we studied that intensely. David designed, conceptualized what those internal capital accounts would look like. Peter Pitegoff and myself put that into legalese, into bylaws, along with some accounts. That became the ICA bylaws, which was geared toward subchapter T. Unfortunately, we looked at conversions, but there was a lot of plant closings going on during this period. We, okay, we can save some of these companies, convert them into worker-owned companies, et cetera.

What we found out, in most of these companies, in an overwhelming majority of these companies, the worker ownership buyout option was the last option they considered because they could not believe, the workers just could not believe that these guys were going to close the plant. They felt this loyalty. They felt there was this love, whatever, and that these guys were not. They’re going to find a way to keep it open. They finally realized, these guys are going to screw us. Who are these guys at the ICA? They said, we should look into worker ownership. By the time we go into the deal, the company had been gutted. It was not a viable business. It needed a lot of capital. We would endeavor to do that, to raise the capital, put together a business plan, try to bring together, because you can just imagine when a company’s like, the Titanic is sinking like that, that management and the workers are not in harmony.

At some point, they’re like, we’re all getting screwed, but the managers, they’re like, we’re working on the effort of the owners. We’re looking to be transferred. They realized, we’re also going to get screwed, but by that time, there’s such bitterness between management and labor that, we’d have to, you guys have to come back together. You’ve got to figure this out, and it was very difficult. There were mostly failures at the large levels there. We focused more on the startups, on the small-scale conversions

At one point, I can literally say from my vantage point at ICA, I represented, I think, all of the worker-owned construction companies. There were about ten of them. They were small, but they were worker-owned construction companies. That was just an extremely interesting period of time.

One tale I love to tell was, I represented this company, I want to call it the Kankakee Boiler Company. They were boilermakers somewhere in Illinois. They were facing a plant closing and a potential buyout from a rival. Either one, they were going to lose their jobs. I think through the state government, they contacted us. I became the guy to go out there and deal with it.

Yeah, these are some Harley-Davidson, tattoo-wearing, some rough. I’d go to some meetings sometimes. I’d be like, “Great.”

John Duda: Not a bunch of hippies looking to start a crunchy granola co-op.

Clark Arrington: No, this was not your soup and sandals group. This was more like Hell’s Angels at work. Long story short, I figured out, I found something in the bankruptcy code, because ultimately, they filed bankruptcy. They had to. I got the senator, and I got the company’s, these little businesses that would have been impacted by the closing, the restaurants, the dry cleaners, all signed my petition. Let us buy it. We can’t buy it at the highest bid. We’ve got to consider what we’re also bringing to the table. We’re going to save jobs. We’re going to support these smaller businesses. Our economic impact is going to be significant. There was this little thing in the bankruptcy code that said, in considering the bid, the judge, the trustees should consider the economic impact. When you go on into the fine print of it, it was really, you should consider the shareholders.

Clark Arrington: That’s what they were referring to as economic impact, not the community impact, but I took this piece and I wrote a brief and submitted it. We’re going to bid, but these guys are prepared to bid, I don’t know how many millions more because they just want the brand.

There’s no way we can outbid these guys. We’re going to have a hearing. Show up, big, big, big hearing in Chicago. When I get there, because I’m scheduled to be in whatever. I’m staying in Chicago. They said, “No, no, no, it’s been moved to the big court.” Okay.

Clark Arrington: I go up to the big courtroom, and the boilermakers showed up. The courtroom is filled with these muscle-bound, tattooed, motorcycle riding dudes. In the middle of the court are the bankers and their lawyers. I’m the only Black cat in the courtroom period. I’m sitting there. I’m like, “Isn’t this interesting? My boys are these rough white dudes that filled up this courtroom.” They had to move the hearing from the smaller courtroom to the main courtroom.

By the time this thing got started, everybody had withdrawn. They withdrew their bids. I didn’t even have to argue my case. Of course, at that point, these guys are like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah!” I become a little hero. I don’t know if I still would be a hero, but I don’t want to speculate on that. It was really fascinating moment for me to have represented this company.

John Duda: This is the work you’re doing now at ICA group, this is really foundational for the growth of worker co-ops in the U.S. Most worker co-ops in the U.S. are using some version of these ICA model bylaws from the ’70s and ’80s, right?

Clark Arrington: Exactly. They have not changed.

John Duda: This is really a key moment of innovation. The legal foundation for worker co-ops in the US wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for this group of people. It’d be gone.

Clark Arrington: I would certainly argue that. We were the pioneers. We did the hard, dirty work. Again, I would credit Steve Dawson, David Ellerman, Peter Pitegoff, myself, Chris Mackin. We did the hard, dirty work. There are others, so I don’t want to act like it was exclusive, but Peter and I were the lawyers. We translated Ellerman’s theories into bylaws

I was able to add to this. I had these crazy guys from Equal Exchange when I was at ICA come to me. I helped them design a company. They’re bringing this fair trade piece to the table. Now, I’m like, “This is really interesting.” I’m going from Black capitalism to cooperatives to worker-owned and now it’s being rounded off with this notion of fair trade.

John Duda: Fair trade is basically new at this point. There are a group of folks inventing it at this point.

Clark Arrington: It did not exist in the United States. It existed in Europe in different models, in particular in Holland. There was the Max Havelaar Foundation. Basically, what the Max Havelaar Foundation did was say, if you subscribe to certain principles, you can use our label. You can put it on whatever your product is. You had a group in Germany. There was a group in Switzerland. At one point, myself and another, Michael Rosine, we toured. We went to Max Havelaar. We went to the Germans. We went to the Italians. To really understand their models, because we wanted to bring it back to the United States

Then there was a point at which they said, “Hey, would you like to work for us?” It was four of them, just a beginning company. They couldn’t pay me a lot of money. This doesn’t get any more exciting or relevant than what we’re doing. Our first coffee was Café Nica from Nicaragua, which, fortunately, the government decided to ban.

John Duda: The U.S. government?

Clark Arrington: Yeah. This is Sandinista. This is the Reagan folk, whatever. Maybe it was George Bush’s people at that time. Of course, we argued, based on how you determine origin of a product, it’s where it was processed. Since our coffee was processed in Holland, the package says it’s a product of Holland. We call it Café Nica. Of course, we’re very proud to say we’re sourcing it from this cooperative the coffee’s grown by, but as far as your regulations, U.S. government, it’s a product of, so we won. We got all this publicity. Time magazine, New York Times. This company’s being banned. Of course, the people wanted the solidarity movement; people who wanted to be in solidarity with the Sandinistas said, “Buy this coffee, man. Yeah, this is how you support the Sandinistas and you’ve got some good coffee,” so that launched the company.

My job, they hired me. They said, “We need you to raise the money, to become the lawyer, be our lawyer and help us raise money.” “Okay, I don’t know much about raising money, but it’s loan agreements and security agreements.” That’s what I did.

I realized at that point, cooperatives need outside money. That’s where we came up with the Class B Preferred onto a Sub[chapter] T. We took the ICA model bylaws, and they added ICA model bylaws with a preferred share. You can, they’re free. You can get those online. You don’t have to pay a bunch of money to get those. That really, quiet as it’s kept. I’m probably over hyping it, but it really changed the playing field because now you could set up a worker-owned business, a cooperative, and have outside shareholders. In the past, one of the problems with a cooperative was that the only way to raise equity was internally. The capital had to come from the workers, and so if the business wasn’t generating sufficient capital to fund growth, you could only do that with debt, meaning you’re tying up your assets, which really slows down your growth. If you can now bring in outside money on an equity basis to support a cooperative, wow.

My understanding, I’m not in this world, but that preferred piece, because part of the preferred piece, why it worked in a cooperative is because you weren’t jeopardizing the integrity of the worker ownership. Generally, capital comes in. The venture capitalists, “Now we’re in control of this. You’ve got to do this, and we’re going to fund you.” It’s like, “No, no, no. We’re going to pay you a dividend if we raise the money, if we earn the money. We’ll make sure your interests are represented on our board, but on our board are going to be other people, basically workers or people who also share our social mission and our goals are not just to maximize profits, if you can accept that.” It turned out to be a bunch of investors out there that accepted that, and they bought the preferred. It made me a little bit of a hero within Equal Exchange,

Then my friend was telling me the other day that there’s this very interesting solar company, Namasté, out in Denver and that they emulated the Equal Exchange model. I imagine there are other companies that said, “Okay.” I don’t think anybody has been able to emulate the social-political impact of the Equal Exchange model. There is clearly a point in time where, through our business model and doing business almost exclusively with cooperatives—we’re sourcing all of our products from cooperatives—we’re also now supporting revolutionary liberation struggles in about four different countries. We’re supporting the AAC in South Africa. We’re supporting the liberation struggle in El Salvador. We’re supporting the Zapatistas in Mexico. We’re supporting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. We’re doing it, we’re not a nonprofit. We’re a for-profit business that’s worker-owned, dealing with other worker-owned businesses, cooperatives.

It happened to be in regions in which we don’t know how much of their money went wherever and who got it, and how everybody related to each other. We know they were part of the struggles in which were going on in those countries for the liberation of those countries. I just don’t know of another company that can boast that kind of activism. At the same time, our preferred—and this is where this model is like—we targeted. We said, “Our dividend’s going to be 3%. We’re going to try to get you 3%. That’s our targeted dividend.” At that point, you talk about dividend in a percentage and a preferred. It can be cumulative or nonaccumulative. If it’s cumulative, that means if you don’t pay the 3%, you still owe it. You can’t pay the common until you’ve caught even with the preferred. If it’s nonaccumulative, if you didn’t pay it, it just didn’t get paid. Move on to the next year.

After eight years of consecutively paying in excess of 3%, averaging basically 5%, the word got out. Not only just socially responsive guys, because you could put your money in Treasuries, and you’re getting 2%, 1%. So, there were a lot of people who were saying, “Yeah, Equal Exchange? I could put my money in Equal Exchange. They pretty much, although it’s not guaranteed, but their track record, and they want to maintain that track record,” because that kept us viable within those markets. People knew, “These guys are going to pay that 4%, 5% every year.” They’re now a $60 million company.

John Duda: Yep. I think this is fascinating, because you’ve got these, basically, words on paper, these legal forms that are being created that are unlocking these hidden potentials in the economy. The economic system is now disclosing, there’s actually a possibility to do a worker-owned business that supports revolutionary movements on two continents. Oh, and it beats Wall Street on returns.

Clark Arrington: Yeah.

John Duda: Which is, I think it’s interesting to just understand the way these kinds of creative experiments.

Clark Arrington: And to fantasize. We’re not. It’s not an impossible world we’re dreaming about. We can have a sustainable, humanistic world based on sustainable economics that treats the earth and its people in a human value-based fashion. Yeah, it’s doable.

John Duda: You mentioned Namasté. I think, aside from the big healthcare cooperatives, I don’t think there’s a single worker cooperative that’s gotten to really significant scale that hasn’t used some variant of this mechanism that was developed with Equal Exchange. I know a lot of the co-ops that are getting off the ground these days, this mechanism, they’ll think about it in terms of crowdfunding, but this Preferred Share Class D mechanism is really a key, key piece of how co-ops are building today, which is remarkable that you were there to crystallize this model.

In Part II of this podcast, Clark Arrington will talk about his work in Africa to advance cooperative economic development and what he currently doing at The Working World.