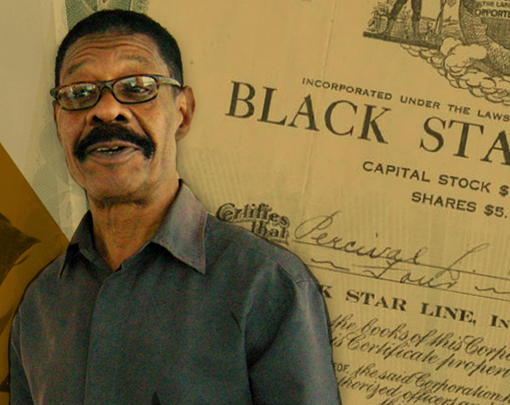

This is the second in a special two-part edition of The Next System Podcast featuring Clark Arrington, a pioneer in the cooperative movement, an innovative legal practitioner, and a leader in the movement for Black economic empowerment. He now works as general counsel for The Working World, which provides creative, nonextractive financing and support for cooperatives. In Part 1, Arrington discusses his start in the cooperative movement and his work with Equal Exchange, which he helped grow from a niche coffee exporter into a $70 million business. In Part 2, Clark talks about what happens when he took his cooperative vision to Africa, and what he’s up to today to help cooperatives finance their vision.

The Next System Podcast is available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Google Play, Stitcher Radio, Tune-In, and Spotify. You can also subscribe independently to our RSS feed here.

John Duda: So, you’re doing all this work. It’s all super, super innovative, and then, you head to Africa. I think that’s where I want to pick up the thread and find out what got you to decamp from New England and head to Tanzania and work in international cooperative development finance.

Clark Arrington: Yeah, I’d say I was blessed. I’m very fortunate in many respects. I’m very fortunate in many respects. After approximately 10 years at Equal Exchange … and New England. I’d moved from Somerville to Cambridge, to, ultimately, Providence.

New England just wasn’t my thing. New England, to me, was impoverished in terms of African American culture. There were no black radio stations. There were no museums. … But, I loved what I was doing with Equal Exchange.

My oldest daughter went to Brown University, the daughter who I moved to Boston for … She went to Brown for me … because I lived in Providence, and she decided she was going to go to Brown. When she graduated, and my parents were deceased, I said, “I want to get out of New England. Maybe I can do something in Africa.”The thought of it just excited me

So, when I’m looking at my options, one of my options was to go to Tanzania. I had been an adjunct at the community economic development master’s degree program. I taught community economic development law, which was just a lot of fun to do. I did that, pretty much, the entire time I was at Equal Exchange. I also served on the board of the Cooperative Fund of New England, which started off with a couple hundred thousand dollars. We’re now $40 million. The Cooperative Fund of New England. We’re the largest, exclusively cooperative-driven loan fund in the United States.

Anyway … Teaching was this opportunity to share what I’m learning at Equal Exchange, what I’m learning at Cooperative Fund of New England. So it was a kind of very worker-owned-cooperative structure legal course.

They had these students starting to come from all over the world. So, the question was, well, is this relevant to have students from the third world, developing world, come to the United States to learn cooperative economic development, as opposed to learning in their own countries? Let’s try this in Tanzania. “Clark, there’s a job opening. Go to Tanzania. We’ve got this relationship with the Open University of Tanzania. Set up a community economic development master’s degree program there. They’ll get a degree from SNHU, and we’ll co-teach all the courses for the first couple of years until we’ve totally transitioned and developed our own.”

And so, that’s what I did. I moved to Tanzania, helped set up this program. It was a lot of fun. I think I taught two semesters.

I had an African counterpart who became basically the dean of the program. Very successful, extremely successful. Produced all these interesting graduates. And, as opposed to a dissertation, the dissertation was a project. So, they had to develop a community economic development project and actually implement it—design it and implement it. That was your final requirement for getting your master’s degree program. Students came on the weekend, like they did at New Hampshire and Manchester. So, I meet the political and social activists in Tanzania, get in on the emerging or emerged cooperative economic development arena, what’s going on. And, I’m living in Tanzania. It was great.

When I left there, somehow, I don’t know how, but I ended up becoming the country director for the African Development Foundation, which was a US government agency that specialized in African development. At that particular time, we had this program that was based on recoverable grants. And so, we would make a grant to an organization, but the organization would agree, very similar to what we do at The Working World, that from basically net profits, they would pay back the grant. But, rather than pay it to the US government, they would pay it to a trust fund that was managed by the Tanzanian technical assistance consulting firm that did their technical assistance.

So, this consulting firm had real incentive to put the business plan together and to work with the group in order to generate these after-tax profits because it would then fund an investment fund that they managed. I was like, “Oh, this is ingenious.” It wasn’t my idea, but certainly added to it. I made a few adjustments. And, while I was there, we had the most loans for any of the African countries. We had the highest impact, and they were all either cooperators or micro-finance.

Now, I became a little disenfranchised, disinterested in the micro-finance. But, it worked on that short-term basis, and particularly for the guys who funded it.

We funded organic cotton cooperatives. We funded the rice cooperatives, we funded the paper … I mean, I traveled all over Tanzania and met with every potential viable cooperative group in Tanzania. I ultimately had to say, “Okay, we’re going to do this deal,” and then, we’d bring in the TA guys. Somehow, they abandoned that project, that concept, but the TA guys in Tanzania now … They’re sitting on over a million dollars of money that they control. So, the vision of not only are we going to fund these groups, but we’re going to do it in a sustainable way that ultimately empowers the Tanzanians because at some point, the United States is not going to be there. But now, the money’s there.

I know one of the interesting projects we were always involved in. This was involved in cotton, and we’re trying to do the organic thing and find out through some of the old folk that they used to do that. They used to have organic pesticides and fertilizers, but it was when the commercial stuff came in, that stuff got put aside, and the people who develop it, they’re no longer farming. So, we went on a wild goose chase to find these guys that knew these formulas, knew these plants and how to put them together. And, ultimately, they were used in this organic cotton project that we funded. So, I had this tremendous experience funding cooperatives.

I came back to the United States for awhile. And then, I ended up at the African Development Bank in Tunisia. And, because of my private sector experience, I was assigned exclusively to this developing private sector division of the bank. Otherwise, they were doing their loans and grants to nation-states, to sovereigns, but they created a division that would actually fund deals. I was their lawyer. I was a consultant. I was there for two years.

So, I had a lot of fun, but even more importantly, I worked with a lawyer there in setting up what we called the African Legal Facility, which was an offshore bank legal facility, first of all, to deal with these vulture funds. You know, defend countries that were being attacked … Robert Murdock or whatever bought their debt and now is coming at them, and he wants to take over their schools and stuff. And then I’m doing extractive industry stuff. We need another model, another paradigm for doing extractive industry. Because what you end up with are the same lawyers—the Brit lawyers are representing the mining company, and the same Brit lawyers are representing the nation-state, so the paradigm doesn’t change.

And, I was really, and I still am very much impressed with the Alaskan Opportunity Fund, in which the citizens of Alaska-

John Duda: The Permanent Fund.

Clark Arrington: Is it the Permanent Fund?

John Duda: Yeah.

Clark Arrington: Okay. Have an ownership interest in the natural resources of Alaska, and I think they get a check from $300 to $3,000 every year. I think it’s been as much as $3,000. It’s been as low as $300. And, I’m like, “What that would do for a country like Tanzania, or any country. That, all of a sudden, this guy in the bush, he’s got $300 coming to him every year. And, he’s basically growing his own food. But now, he’s got this cash. And, everybody in the village has got this cash.”

So, one of the things we did with this African Legal Support Facility was create the opportunity to look at another paradigm or extractive industry deals, so that, yeah, why couldn’t you have a corporation that—and, it’s one of the things I’m working on in Tanzania—where you have your investors, you have your workers, and then, through the public stock exchanges, you have the public. So, you have three ownership groups, the workers who are cooperatively owning this piece. Then you have your investors, and they’ve carved out their, basically, class B-type piece. And then, you have the stock exchange folk, the public, and, in a country like Tanzania, you can buy shares at the grocery store.

John Duda: Interesting.

Clark Arrington: Yeah. It’s not like here, you got to get a broker, dealer, and pay him … No, no. Of course, they don’t have as many companies. But, the information’s all public. It’s like you got to dig in. It’s all very accessible. And, they require the telecoms, for instance. If you’re in telecom within whatever period of time, you have to sell to the public. So, they’re demanding public participation in key sectors, which is like, yeah. Why not? So, let’s do that in extractive industries, where we also have a worker-owned component.

So yeah, I had an interesting time. I came back from the bank, and I ended up working for this very large law firm. The guy, Nimrod Mkono. He was Nyerere’s lawyer.

John Duda: Oh, wow.

Clark Arrington: Yeah. And, he’s like a walking encyclopedia about Nyerere and about, basically, the law in Tanzania because he was there at Independence. They basically transitioned British company law into Tanzania company law and then made the modifications, et cetera.

So, I’m working for him, and a lot of it was just really insightful … It just got into some aspects of Nyerere and ujamaa and African socialism. He continued … There was a lot of critique about the Tanzanian approach to socialism and to African socialism and their cooperative models. Because their cooperative models … I mean, one of the things I think Nyerere did that was—I certainly wouldn’t have done it today done it today—But, the government was really involved in all of the cooperatives, and what they created was very similar to, I guess you would say, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, where you had an apex unit. The cooperative model was an apex with the top being the government.

The failure of that cooperative structure was as much the fault of the people who betrayed him, who were in his system, who allowed that to happen, who abused that system. You know, they might not even go to the meeting, but they’re still… Or, they only really needed $100, but they took $500. And then, there was the drought, just a lot of other circumstances beyond Nyerere’s control that had a negative impact on their attempts at socialism.

But, Mkono was there. But, Mkono had evolved into … You know, Nyerere left office, and, of course, although he was part of the revolutionary struggle, being Mkono, being Nyerere’s lawyer, … he got good government contracts. And, the public sector was where the money was. It wasn’t in the private. The private sector was evolving. And so, through contracts with the public sector, you developed relationships with the European firms. So then, you could then justify paying $400-$500 an hour because there was some international deal. IBM’s coming to town, or whoever. And, you can handle it because you’re now affiliated with Ropes & Gray out of London. I also saw corruption right in front of my face and basically was told to ignore it. Not to do anything. Nobody did anything. I’m the only one raising hell, like “Where are the receipts? Where’s the documentation? How do we know this money?” Here’s a letter, and you know, I’m realizing, oh, man, this is… So, I left.

And, I tried to set up a center for community economic development at Nyerere University, at this university that was the first university in Tanzania. It was set up to train the civil servants to take over the country. So, they weren’t necessarily interested in giving you a four-year degree. They were interested in teaching you skills. You know, how to collect taxes, how to run the harbor, how to manage the defense forces, et cetera, et cetera. Which is another problem Nyerere had. He was attacked by Idi Amin. And, you got to say, “Okay. Was this some CIA bullshit?” You know, let’s provoke this guy into attacking Nyerere, and we’ll really put a crushing blow. And, war drains your resources. They couldn’t afford that war. Now, they want it. They marched down the streets of Kampala. But, that was a drain on the resources. So, there’s a lot of corruption stuff …

John Duda: It doesn’t discount the impulse behind the model.

Clark Arrington: Right. No, exactly.

John Duda: The economic alternative is not discounted by the history because the history is messy and complicated.

Clark Arrington: So, I come back to the United States because I had too many friends dying that I wasn’t able to—It was like damn, I didn’t even say goodbye to this cat. And then, my grandchildren are growing. Now, my daughter would come to Tanzania at least once a year with the kids. So, I was guaranteed to see them at least once a year, even if I didn’t come back to the United States. But, it’s like a two-day trip from Tanzania to the United States. You fly north, and then you fly east-west. So, I decided it was time for me to come back. I needed to connect with relatives. In particular, I needed to watch my grandchildren grow. So, I came back.

I come to Baltimore with my daughter. I do some teaching, and then through Chris Mackin, he says, “I want to introduce you to Brendan Martin at The Working World. They’re looking for some project directors.” And, I was like, “Oh, okay. Wow, they do worker ownership? Oh, interesting.” So, I send my resume in as being a project director. Brendan’s like, “I don’t think so, but wow, you’ve got an interesting background. You’re the Equal Exchange guy? Let’s talk.” So, we carved out this position, basically, for me to be general counsel. And, I start work at The Working World.

Let it be told that here again, I find myself on the cutting edge of cooperative economic development and being able to contribute. With The Working World, again, this is Brendan Martin, and I’m translating into legalese. But, we have this profound financing approach, in which we’re only receiving net payment. We’re only receiving loan repayments from net proceeds, from after-tax income. And, it’s crazy because we’re calling it a loan, and I’m like, “Brendan, this ain’t a loan. You can say it’s a loan.” It’s just like you can say that duck is a dog, but when the duck starts flying … You know what I’m saying? It’s hard to argue that this thing with feathers that’s flying and is doing quack-quack is a dog. So, we can say it’s a loan, and it’s a promissory note, but if the proceeds, if the repayment is only coming from after-tax income, there’s no default. If they don’t pay, they don’t pay. You can’t say, “Oh, you guys didn’t pay us.” And, even if they had surplus, the way it’s currently structured—because after-tax distributions are determined by the board of directors at their discretion, because it’s after-tax. So, if you want to pay the dividend, you can pay the dividend.

I had this group of young lawyers when I came back, like, “Oh, you’re Clark Arrington.” Yeah, I’m Clark Arrington. The guy who got fired from the African Development Foundation, but yeah, I’m that guy. “Oh, but you’re the Equal Exchange guy. You’re the ICA guy. You’re the Southern New Hampshire University guy.” So, I have this little cadre of really bright, young lawyers.

And, of course, the 15 years in which I was away in Africa, the cooperative movement blossomed. When I left, I knew all the lawyers. I pretty much knew all of the businesses. Like I said, I represented all the construction companies, and I represented all the symphony orchestras. I come back, and it’s like, there’s cooperative groups everywhere. They’re teaching it in colleges. There are all kinds of webinars. It’s like, wow. And, all of a sudden, I’ve got a little bit of notoriety just by virtue of the fact that I was involved some years ago. And, I’m pleased that the projects that I was involved in are very successful. I don’t really try to take any credit for whatever, but I’m just pleased I was involved, and I was able to make a contribution. And, I’m able to do that now with The Working World. There’s a lot that Jeff and I have done to really streamline, improve the way we lend money to cooperatives.

So, we’re creating different models. We’re still in deep research. But, one of the things we do, as I was mentioning: In the co-op movements in Europe, either the state, or in Mondragon, the Caja Laboral, the finance folk …

John Duda: Laboral Kutxa now, right? Yeah.

Clark Arrington: Yeah. Well, they used to, and, they still do. They want an ongoing piece of the action to continue the cooperative movement. It’s like some people sacrificed for you to be here. Now, you’ve got to … right.

So, we have what we call our golden share. So, even after our loan is repaid, we’re still in the deal through our golden share, of which those funds now go to a pot that’s used to fund other co-ops. And, as you may know—you must know; yeah, obviously, you know—The Working World is converting into what is called the Seed Commons. If this is successful, there will be a network of cooperative funding institutions throughout the United States that will be affiliated through an MOU [memorandum of understanding] with this thing called the Seed Commons, which will be like the central bank for this network of local cooperative financial institutions, all using the same non-extractive-payment, after-tax process for making loans. Which, will be very, very exciting. Which will radically change finance. But, we’re at the infancy.

John Duda: So, the idea here is not just to make a couple loans to some co-ops, but it’s really to build a whole ecosystem for non-extractive finance.

Clark Arrington: Exactly. Exactly.

John Duda: And, to solve that equity problem at a larger scale.

Clark Arrington: Right. The equity and the technical assistance problem. So, if the TA and the capital are coming at the local level … Although, yeah, there’s the Big Brother. There’s the Caja Laboral … But, at the local level, you’ve got the TA. And, you got the capital. You’ve got access to the capital. And, just as we did in Africa with the consulting firm having a vested interest in the success of the cooperative because they’re going to get repaid, it’s the same model … I had nothing to do it. It’s just the same model that we’re now using in seed capital.

The question is, can that be scaled out? Can it scaled up? Can it be transferred to Cincinnati? Can there be exchange in the TA and the business plans? Now, maybe even in the purchasing power, the marketing power. So, the potential is just … When you talk about a solidarity economy and creating a new economy, The Working World is right at the cutting edge of doing that, man. And, I just happen to be their lawyer.

John Duda: So, you’re the guy who has to make sure that everything is airtight, so when they come after it like they came after Garvey or New Communities, or what have you-

Clark Arrington: Or, the Federation …

John Duda: Yeah, or the Federation … that this thing stands up.

Clark Arrington: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Anyway. So, that’s where I’m at. I love it. I work with some great people, and I’m having the time of my life right now.

John Duda: That’s super, super exciting. This is, I think, just in general, the amount of creativity of catalyzing these economic solutions, based on these legal interventions, is really fascinating. And, you say you’re working pretty actively to train up a new generation of folks to do this work?

Clark Arrington: Yeah.

John Duda: Maybe a good place to end is just to give me a sense of what you try to tell these folks who are coming up, who are really excited about this work. What are you trying to tell them to do?

Clark Arrington: I think the key, the strong lesson I try to provide them—and, they’re all very brilliant young people; they understand you need to understand business law—this is not social justice stuff. This is economic justice stuff, and we need to understand securities. We need to understand tax. We need to understand entities. But, that we can’t continue to adapt existing structures to our structures. We have to now begin creating structures that are customized for what we’re doing. They’ve gone through a series of creating these cooperative statutes, and they’re based on the Rochdale notion of a cooperative. But, that’s not what a cooperative is anymore.

We’re talking about certain principles. And, we can live with Sub T but maybe we need to create some other types of entities. Same thing with capital formation. Maybe there’s another way we can raise money. Now, like I said, we’re pushing the envelope. If we’re successful, the investor should be successful, even though we’re a nonprofit.

: So, this whole notion of private inurement: If we’re eradicating poverty, which is what—we’re a 501(c)(3); our public purpose is to eradicate poverty. And, there’s this other area out there. It’s called social impact investing, and this is Goldman Sachs—I mean, these are big boys; they’ve figured out some deal where they go in and finance a nonprofit, and if the nonprofit meets certain targets, then the government or some third party pays them their money back plus a big bonus. And, that’s not private inurement? That sounds like private inurement to me. So, “it was just another way of doing procurement.” Yeah, but this is Goldman Sachs saying, “I’m putting up a million dollars, and we’re going to try to make sure these targets are hit, and do they do, then we get a million point five back.” Oh, okay. So, you made $500,000 on your million, and you’re now bragging about the social good you did, but this was very, very profitable for you. And, nobody’s arguing about that, and we need to have the same sort of incentives on the cooperative development side.

So, it’s like, “Hey, young lawyers, let’s figure out ways, not just totally be adapting to what’s in existence. But, let’s create new entities, new structures, new transactions.” Like I was saying about in Africa … If you stick with the old paradigm, the country gets royalties, and we get to employ certain people. Yeah, no. The country should own the deal, you lease it out to these guys, and they get the royalty for what they produce. And, the net profits go to the country, and if the country’s owned by the citizens, then that money is distributed to the citizens on a cooperative basis.

Clark Arrington: Anyway, that’s me, man. I thank you for unloading.

John Duda: All right. Thank you so much. This is really great.